Rajendra Prasad Defied Nehru and Opened Somnath Temple

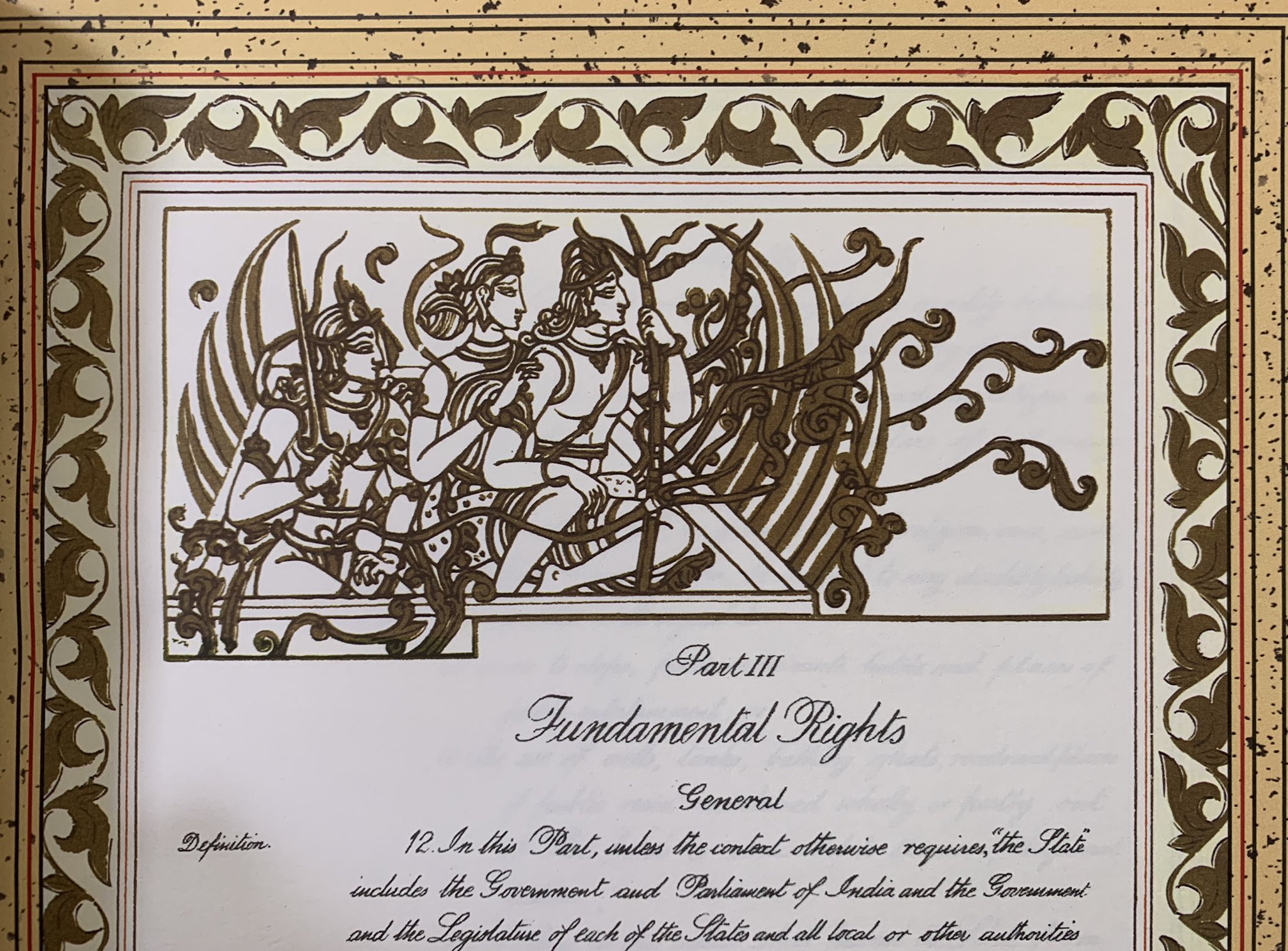

Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad today tweeted with the picture:

"Original document of the Constitution of India has a beautiful sketch of Lord Ram, Mata Sita and Laxman returning to Ayodhya after defeating Ravana. This is available at the beginning of the chapter related to Fundamental Rights. Felt like sharing this with you all. "

|

After Rahul Gandhi’s 29 November 2o17 visit to the Somnath temple, Prime Minister Narendra Modi noted that Rahul had decided to “suddenly visit Somnath dada (the deity)” when his great-grandfather Jawaharlal Nehru didn’t even want the temple to be reconstructed. “(Nehru) had expressed displeasure with the reconstruction undertaken by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. If it wasn’t for Patel, the temple wouldn’t have been reconstructed,” Modi said.

What exactly happened in those years immediately after Independence? Was India’s first Prime Minister, indeed, uncomfortable about reconstructing the temple? Why?

The ancient Shiva temple at Somnath, close to Veraval in Gujarat’s Gir Somnath district, was ravaged in 1026 by Mahmud of Ghazni, who looted its riches and broke the idol — the best known among multiple attacks by a series of raiders who were drawn by the temple’s legendary wealth over the centuries. In 1842, Lord Ellenborough, Governor-General of India, issued his famous ‘Proclamation of the Gates’. Ellenborough, historian Romila Thapar recorded, asked the British army in Afghanistan to return via Ghazni, bringing back the “sandalwood gates of Somnath” that the medieval conqueror was believed to have taken away. What his forces brought to India, however, turned out to have nothing to do with Somnath. (Somnatha: The Many Voices of A History, 2004).

In the years leading up to Independence and Partition, the narrative of Hindu pride found many takers, among them K M Munshi, a Congress leader from Gujarat with strong Hindu nationalist leanings. Somnath, whose destruction had until then been of largely regional interest, was elevated into the consciousness of a deeply divided nation as a symbol of Muslim intolerance and iconoclasm.

What exactly happened in those years immediately after Independence? Was India’s first Prime Minister, indeed, uncomfortable about reconstructing the temple? Why?

The ancient Shiva temple at Somnath, close to Veraval in Gujarat’s Gir Somnath district, was ravaged in 1026 by Mahmud of Ghazni, who looted its riches and broke the idol — the best known among multiple attacks by a series of raiders who were drawn by the temple’s legendary wealth over the centuries. In 1842, Lord Ellenborough, Governor-General of India, issued his famous ‘Proclamation of the Gates’. Ellenborough, historian Romila Thapar recorded, asked the British army in Afghanistan to return via Ghazni, bringing back the “sandalwood gates of Somnath” that the medieval conqueror was believed to have taken away. What his forces brought to India, however, turned out to have nothing to do with Somnath. (Somnatha: The Many Voices of A History, 2004).

In the years leading up to Independence and Partition, the narrative of Hindu pride found many takers, among them K M Munshi, a Congress leader from Gujarat with strong Hindu nationalist leanings. Somnath, whose destruction had until then been of largely regional interest, was elevated into the consciousness of a deeply divided nation as a symbol of Muslim intolerance and iconoclasm.

|

| Somnath in ruins before reconstruction |

The first major articulation of the intention to rebuild the ruined temple is believed to have been made by Sardar Patel, Nehru’s Deputy Prime Minister, at a huge public meeting in Junagadh on November 12, 1947. The nawab of Junagadh had fled to Pakistan, and the Indian Army had moved into the estate.

In one of several blogs written between 2009 and 2014 (later compiled into a book, My Take, 2014), L K Advani, said: “After returning to Delhi, (Patel) secured Gandhiji’s blessings for the (temple reconstruction) and had Pandit Nehru have it endorsed by his Cabinet. The Cabinet’s decision implied that the Government would incur the expenditure. But that evening itself, when Sardar Patel, Dr Munshi and N V Gadgil went to Gandhiji to apprise him of the Cabinet’s decision, Gandhiji welcomed it but added: Let the people and not the Government bear the expenditure.” Accordingly, a Trust was set up, with Munshi as chairman.

With Gandhi’s assassination, the Congress lost the glue that bound a set of patriots with disparate ideologies and aspirations, but who shared the one dream of a free India. The wounds of Partition were raw, and Nehru, stridently pseudo secular, had open differences with several partymen, including Patel, on issues ranging from the treatment of minorities to the choice of President .Nehru rooted for C Rajagopalachari; Patel wanted Dr Rajendra Prasad.

In December 1950, Patel died. The “one Congress leader who was of equal standing to Nehru”, was removed, historian Ramachandra Guha wrote in , India After Gandhi: The History Of The World’s Largest Democracy. One other opposing power centre now remained: Rajendra Prasad. The differences between the President and the Prime Minister came to the fore once again in 1951, when it was time to inaugurate the rebuilt Somnath temple.

In his Pilgrimage To Freedom, Munshi wrote that after a Cabinet meeting in early 1951, Nehru called him and said, “I do not like your trying to restore Somnath. It is Hindu revivalism.” Munshi, then the Food and Agriculture Minister, wrote to the Prime Minister in reply: “Yesterday you referred to Hindu revivalism. You pointedly referred to me in the Cabinet as connected with Somnath. I am glad you did so; for I do not want to keep back any part of my views or activities… I can assure you that the ‘Collective Subconscious’ of India today is happier with the scheme of reconstruction of Somnath… than with many other things that we have done and are doing.”

He then went ahead with his plan and approached President Prasad to inaugurate the rebuilt temple. Madhav Gobole, who was home secretary when Indira Gandhi was Prime Minister, and the author of The God Who Failed: An Assessment Of Jawaharlal Nehru’s Leadership (2014), points out that this incident alone — when a Minister was able to go ahead with his plan despite the PM’s obvious displeasure — proves this: “We all consider Nehru to be this all-imposing, supreme leader, but the truth is, he had his limitations. In his Cabinet, he had people with all kinds of opinions, but he believed he would be able to persuade them to come around to his view. Sometimes he was successful, sometimes he was not,” Godbole said.

Nehru persisted, writing to the President, asking him to reconsider his decision to inaugurate the temple. He wrote to Prasad: “I confess I do not like the idea of your associating yourself with a spectacular opening of the Somnath temple. This is not merely visiting a temple… but rather participating in a significant function which unfortunately has a number of implications.” (Sarvepalli Gopal, Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru).

|

| Somnath temple with Patel statue |

Guha records:"Partition had just happened. Millions of Muslims had stayed back in India and Nehru said that was enough affirmation of their citizenship; they don’t need to go through some kind of loyalty test. He was very conscious of their vulnerability and insecurities. Hindus and Muslims had been at each other’s throats only a couple of years earlier, and Nehru didn’t want to polarise communities again, reopen old wounds just when India was settling down. Those were fragile times, and Nehru thought it was unnecessary for the President to associate himself with a temple that was destroyed by a Muslim invader hundreds of years ago, when Muslims of India have nothing to do with Mahmud of Ghazni.”

I don't subscribe to this.The fact is,Nehru never liked Rajendra Prasad.He had blocked Prasad when he wanted to see the discussion in the Lok Sabha from the President's enclosure.Nehru reprimanded the President by saying the enclosure was for the President's guests.

Prasad decided to inaugurate the temple anyway. On May 2, 1951, a distressed Nehru wrote to Chief Ministers: “It should be clearly understood that this function is not governmental and the GoI has nothing to do with it… We must not do anything that comes in the way of our state being secular. This is the basis of the Constitution and governments, therefore, should refrain from associating themselves with anything that tends to affect the secular character of our State.”

Prasad wrote back, saying, “I believe in my religion and cannot cut myself away from it.” (Durga Das, India: From Curzon To Nehru And After, 2004)

On May 11, 1951, the President inaugurated the grand, rebuilt Somnath temple.

Rajendra Prsad and Patel were Gandhi's true disciples,whereas Nehru was not.

|

| K. M. Munshi with archaeologists and engineers of the Government of India, Bombay, and Saurashtra, with the ruins of Somnath Temple in the background, July 1950. |

Located near Veraval, at Saurashtra in the western coast of Gujarat, the Somnath temple is believed to be the first among the 12 jyotirlinga shrines of Shiva. The site which was part of the erstwhile princely state of Junagadh, is also connected to Lord Krishna. Most historical accounts suggest that the temple was ravaged in 1026 CE by the Turkik ruler, Mahmud of Ghazni who looted its riches and desecrated the idol.

In the years preceding the Independence of the country, K M Munshi, a Congress leader from Gujarat, expressed his disappointment at the nation’s inability to rescue the spot of Krishna’s worship for all these generations. “My heart was full of veneration and shame. Millions have worshipped and worship today, Shri Krishna as ‘God himself’…none had dared to raise his voice to rescue the sacred spot where once His mortal remains had been consigned to flames… Reconstruction of Somanatha was then but the nebulous dream of a habitual dreamer,” Munshi wrote in his book, ‘Somanatha: the shrine eternal’, recollecting his visit to the ruins of the ancient temple in 1922. Munshi’s words had turned the issue of Somanatha from a largely regional issue to one of national and Hindu pride.

At the time of India’s Independence, the nawab of Junagadh decided to accede to Pakistan, even though 82 per cent of Junagadh’s population was Hindu. The Indian National Congress formed a parallel government and led an uprising against the nawab who fled to Pakistan. Consequently, the dewan handed over Junagadh to Indian administration.Soon after, on November 12, 1947, the then home minister of India, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel visited Junagadh.

A trust was created with Munshi as its chairman.

|

| Rajendra Prasad in Somnath Temple |

With the death of Patel in 1950 though, the responsibility of the reconstruction fell on Munshi’s shoulders. Since the Independence of the country, Patel and Nehru had been at odds on many issues ranging from who should be president of the country to who should take the presidency of the Congress party. On the question of minorities too, the two stalwarts were at odds. “Nehru felt that it was the responsibility of the Congress and the government to make the Muslims in India feel secure. Patel, on the other hand was inclined to place the responsibility on the minorities themselves,” writes historian Ramachandra Guha, in his book, ‘India after Gandhi’.

Guha further notes that Patel’s death “removed the one Congress politician who was of equal standing to Nehru.” But the prime minister still had to deal with differences with two other leaders — Congress president Puroshottamdas Tandon and President Rajendra Prasad. “It was clear that the prime minister and the president differed on some crucial subjects, such as the place of religion in public life,” writes Guha.

Later Munshi went ahead with his plans and asked Prasad to inaugurate the temple. When he heard of Prasad’s presence at the event, Nehru was appalled. He wrote to him expressing his disapproval. “Personally, I thought this was no time to lay stress on large-scale building operations at Somnath. This could have been done gradually and more effectively later. However, this has been done. [Still] I feel that it would be better if you did not preside over the functions,” he wrote.

While Prasad disregarded the advice of the prime minister and went ahead with the inauguration ceremony, he was sure to emphasise on the Gandhian ideal of inter-faith harmony in his speech at Somnath. He pointed out that to reconstruct the temple was “not to open old wounds”, but rather “to help each caste and community obtain full freedom”.

At Somnath, Prasad justified his idea of state and religion thus: “I respect all religions and on occasion visit a church, a mosque, a dargah and a gurdwara.”

© Ramachandran