Gandhi wrote to George Joseph on 6 April 1924:

The representatives of the three organisations on 17 Decembetr 1932 formed the Samyuktha Rashtriya Samithi ( Joint Political Conference).A deputation submitted a petition to the Dewan,Thomas Austin on 9 January 1933.Austin ( 1887-1976 ) was an ICS officer of the 1910 batch;he was district Collector of Nilgiris during 1929-32.Later,he was Chief secretary,Madras.Austin Town in the city of Bangalore, is named after Thomas Austin who had built houses for low-income groups in the Cantonment section of the city.

The Joint Political Conference met on 25 January 1933 and passed a resolution that its members ' should abstain from taking part either by voting or by standing as candidates in the elections or by accepting nominations to the Legislature so long as the Government did not make adequate provision for the representation by election of all communities in proportion to their population in the Legislsture'.

To win the sympathy of of the British,the Conference drew a distinction between 'Abstention'( Nivarthanam) and 'Non-Cooperation'( Nissahakaranam) of Gandhi.The Viceroy Lord Willingdon was engaged in a campaign to crush the Non- Cooperation movement in India.The Travancore Government could not be deceived.The agitation continued to the end of 1933 when the Travancore Givernment in their attempt to eliminate the protest before the arrival of the Viceroy in Travancore,served a notice to the Christian news paper,Malayala Manorama,whose publisher K C Mammen Mappillai was a financier of the movement,to show cause why legal action should not be taken against it for supporting the agitation.It should ne noted that the Dewan was not Sir CP,the Dewan was a christian,Thomas Austin.A gag order was imposed on its leaders N V Joseph,P K Kunju and C Kesavan.It was in this back drop the Thangassery episode took place.

While the Christian,Thomas Austin was the Dewan,the leaders of the movement and its supporters till now have blamed Sir C P Ramaswamy Iyer,who was only the constitutional Advisor to the King,for suppressing the agitation,because he took steps to close the Travancore and National Quilon Bank later as Dewan in 1938-Mammen Mappilai was the one who had founded the Travancore Bank.

|

| Viceroy Willingdon |

The determination to take over Thangassery was resisted by the inhabitants,who wanted their special British protectorate status.On 24 June 1934 the inhabitants passed a resolution to the British crown,to protect their status.A petition was submitted to British authorities in Madras,who then decided not to transfer without the concurrence of the inhabitants.On 15 January 1935,a counter petition was submitted to the Vuceroy by those wished for the merger.In response to this,another petition was drawn up,with demands similar to that of the Abstention movement.At the suggestion of Mammen Mappilai and others,early in 1935,M M Varkey,a stooge of Mappilai,was despatched to Madurai to meet George Joseph.George agreed to act an emissary to the Viceroy,if he was authorised by the people.A revised petition with clear authority to act on behalf of the people was given to George.

George and Varkey went to Madras and met the Governor Lord Erskine.From there they went to the offices of The Hindu and and Madras Mail,and keeping with Geoge's character or the lack of it,gave unwanted media exposure.George Joseph spoke at the local Congress meeting on prohibition,when invited.But George exploded against the very idea of prohibition,and the journalists surrounded him.He spoke about the Abstention movement and plight of the thangassery inhabitants in Travancore.In his trip to Delhi fro Madras,in every railway station,the press approached him for more.Before leaving for Madras he had informed of the developments in Travancore,to William Wedgewood Benn,former Secretary of State for India ( 1929-31 ) and the Duchess of Atholl,British Hostess of political soirees.Duchess of Atholl,Katharine Marjorie Stewart-Murray resigned the Conservative Whip in 1935 over the India Bill.

|

| Duchess of Atholl |

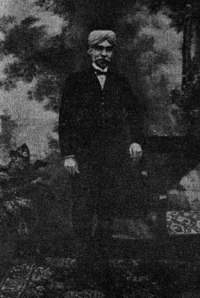

|

| Habibullah |

|

| C Kesavan,T M Varghese,George Joseph |

"We do not want that 'Jantu' (creature).I did not say 'Jantu' but Hindu. He will do no good to the Ezhava, Christian and the Musalman. When I say this I do not see any play of protest in the countenance of any one of you. It is after the arrival of this gentleman here that such a bad name about Travancore state has spread outside. Unless this man leaves the country, no good will come to it. We have achieved these things by the joint organisation of our three communities."

Calling one a Jantu ( animal ) was a statement of hatred,not of criticism.

A week later,Kesavan was charged under section 117 of the Travancore Penal Code for exciting contempt and feelings of disaffection towards the Government.George Joseph was appointed the defence counsel.He was to make a journey from Madurai to argue the case and return there on the completion of the hearings.Since it was believed that George Joseph's arrest was a strong possibility,the Kottarakara railway station was the only safe venue for the discussion of the case and the political events of the day since the railway stations constituted British territory and thus were outside the jurisdiction of the Travancore authorities.Kesavan was found guilty and sentenced to two years' imprisonment and a payment of a fine of Rs 500.

The signatories were: K.K. Chandy, S. Gnanaprakasam, S. Gurubatham, S. Jesudasen, M. P. Job, George Joseph, K.I. Matthai, A. A. Paul, S.E. Ranganadham, A.N. Sudarsanam, O. F.E. Zacharia, D.M. Devasahayam, G.V. Martyn ( Only 13 names are on record.)

Ambedkar had announced in a speech at Nasik in 1935 that he will renounce Hinduism. In the same year a meeting was held at Yevala in which through a resolution a decision was taken to the effect that "we should Denounce the Hindu religion". In that meeting Ambedkar had said, "though both a Hindu because I could not help it, I would not die as a Hindu." Gandhi described this as a "bombshell".

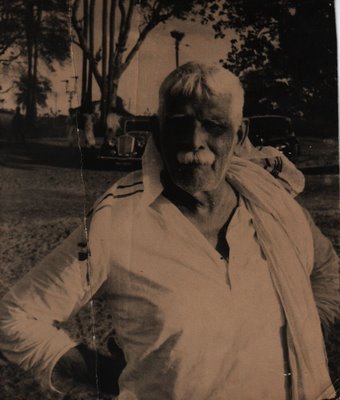

|

| Thomas Austin |

Kesavan's conviction aroused some of his Ezhava community friends even more and a section among them sought mass conversion to Christianity.They approached George Joseph on this matter.According to the biography,George Joseph:The Life and Times of Kerala Christian Nationalist,George Joseph's attitude was some what ambivalent.While any addition to the Christian fold was welcome to some one with his recently acquired Christian convictions,he was uneasy about the non-religious motivation underlying the intended mass conversion.He counselled caution when a number of Christian organisations wanted to take a more active role in promoting this project.This was also the time that he corresponded with Ambedkar regarding the efficacy of mass conversion as a political weapon to improve the status of the untouchables.However more favourable circumstances,notably the Temple entry Proclamation led many Ezhavas to reconsider the original plan of embracing Christianity.

The book claims that this conversion movement had the approval of SNDP Yogam-it can't be true becuase Sir C P had made several Ezhavas including Kumaran Asan Sree Moolam assembly members and eventually before Sir C P left Kerala,SNDP Yogam held farewell meetings in honour of him.R Sankar was a close friend of Sir CP.Sir CP allotted 27 acres of prime land to build the SN College free of cost,at the heart of Quilon town.Sankar and associates expressed their gratitude to Sir CP.Kesavan who was an atheist and anti Hindu, instead of condemning the Sabarimala Temple burning,applauded it by saying that destruction of temples would eradicate superstitious beiefs in society.

Incidentally it was Narayana Guru,renaissance leader and life long President of SNDP Yogam and Kumaran Asan,the Illustrious General Sceretary of SNDP,who vehementally opposed the conversion move of a group of upstarts and insisted that there is no religion equal to Hinduism in providing spiritual freedom and enlightenment,in a well known article,titled,Mathaparivarthana Rasavadham,a treatise on religious conversion.

George Joseph,who had supported Fascism as a rival to Communism after he left Gandhi,began to preach Christianity among the depressed classes and in 1937,a manifesto was issued by 14 Indian Christians including him,for conversion of the depressed classes to Christianity.George Joseph,a soldier of Christ,who had become an evangelist wanted to convert the depressed classes who constitute a majority of the Hindu population as a prelude to forming a Christian theocratic state in India.

|

| Gandhi with Harijans |

"Disagreements with Gandhi went beyond differences concerning specific facts about the motives for and consequences of conversion.Whereas Gandhi considered all religions on par,if not similar,in that they were both true and flawed,the Christians saw religions as basically distinct,each with differing gifts to offer.Moreover,whereas Gandhi sought to remove untouchability and the disabilities from which untouchables suffered without destroying the existing socio-religious order,the Christians,like Ambedkar,considered social conflict the inevitable price of meaningful change.This comes out clearly in many Christian statements including the one on "Christian Attitude to Harijan Revolt" issued by the Bangalore Conference Continuation in June 1936.This statement,unlike a later one,"Christian Evangelism in India", prepared by the National Christian Council ,was sensitive to reformist Hindu concerns and fearful of aggravating communal rivalries.It therefore urged Christians to continue their work among untouchables with great care and even to exercise a "ministry of reconciliation between caste Hindus and Harijans."

It further states:

"Perhaps the most thoughtful and sensitive Christian response to Gandhi's concerns came from a group of fouteen nationalist Christians who wrote a careful statement entitled,"Our Duty to the Depressed and Backward Classes:An Indian Christian Statement," in March 1937.On one hand,it recognized the fact untouchables were seeking the fellowship of the church and that it was the duty of the Christian Church to receive such seekers as well as to awake spiritual hunger.On the other,it urged restraint,so as not "to alienate the sympathy and spoil the open mindedness of the Hindu to the Gospel by any ill-considered attempts at external results of a questionable value".

Barrister George Joseph was one among the 14 signatories.

Gandhi replied:

"The duty of the Christian Church in India is turned into a right.Now when duty becomes right it ceases to be a duty.Performance of a duty requires one quality-that of suffering and introspection.Excercise of a right requires a quality that gives the power to impose one's will upon the resister through sanctions devised by the claimant of the law whose aid he invokes in the excercise of his right.I hsave the duty of paying my debt,but I have no right to thrust the owed coppers ( say ) into the pocket of an unwilling creditor.The duty of taking spiritual message is performed by the messenger becoming a fit vehicle by prayer and fasting.Conceived as a right,it may become an imposition on unwilling parties."

The Editor of The Guardian,one of the 14 co-signers took issue with Gandhi's remarks and concluded that Gandhi's criticism does not allay Muslim and Christion suspicions that "Mahatma Gandhi is a downright communalist and cannot but fight as a Hindu inspite of his nationalism."

|

| Ivanios,1908 |

George Joseph briefly returned to Congress,failed in Muncipal elections and in his practice as a lawyer,again left Congress and then got immersed in Roman Catholicism.His conversion to Catholicism was triggered off when Mar Ivanios,a Syrian Orthodox Archbishop acknowledged the authority f the Pope as the head of all Christian churches in 1931.Mar Ivanios was lured by a heftuy sum from Rome,according to his detractors.George Joseph joined the break away group led by Mar Ivanios.He began to campaign for the Christians and more specifically for the Catholics in the political arena.

Towards the end of his life,George paved the way for the closure of Kerala Kaumudi.On George's 50th birth day on 5 June 1937,he presided over a political conference at Punalur.There he was taken in a large procession led by caparisoned elephants.For Kerala Kaumudi,edited by Kesavan,George sent a message,which was published on 7 March 1938,two days after his death.The message read:

Segaon, Wardha

April 3, 1937

Fourteen highly educated Indian Christians occupying important social positions have issued a joint manifesto setting forth their views on the missionary work among Harijans. The document has been published in the Indian Press. I was disinclined to publish it in Harijan, as after having read it more than once I could not bring myself to say anything in its favour and I felt that a critical review of it might serve no useful purpose. But I understand that my criticism is expected and will be welcomed no matter how candid and strong it may be.

The reader will find the manifesto published in full in this issue. The heading(1) is also the authors'. They seem to have fallen between two stools in their attempt to sit on both. They have tried to reconcile the irreconcilable. If one section of Christians has been aggressively open and militant, the other represented by the authors of the manifesto is courteously patronizing. They would not be aggressive for the sake of expedience. The purpose of the manifesto is not to condemn uniquivocally the method of converting the illiterate and the ignorant but to assert the right of preaching the Gospel to the millions of Harijans. The key to the manifesto is contained in paragraphs 7 and 8. This is what one reads in paragraph 7:

"Men and women individually and in family or village groups will continue to seek the fellowship of the Christian Church. That is the real movement of the Spirit of God. And no power on earth can stem that tide. It will be the duty of the Christian Church in India to receive such seekers after the truth as it is in Jesus Christ and provide for them instruction and spiritual nurture. The Church will cling to its right to receive such people into itself from whatever religious group they may come. It will cling to the further right to go about in these days of irreligion and materialism to awaken spiritual hunger in all."

These few sentences are a striking instance of how the wish becomes father to the thought. It is an unconscious process but not on that account less open to criticism. Men and women do not seek the fellowship of the Christian Church. Poor Harijans are no better than the others. I wish they had real spiritual hunger. Such as it is, they satisfy by visits to the temples, however crude they may be. When the missionary of another religion goes to them, he goes like any vendor of goods. He has no special spiritual merit that will - distinguish him from those to whom he goes. He does, however, possess material goods which he promises to those who will come to his fold. Then mark, the duty of the Christian Church in India turns into a right. Now when duty becomes a right it ceases to be a duty. Performance of a duty requires one quality - that of suffering and introspection. Exercise of a right requires a quality that gives the power to impose one's will upon the resister through sanctions devised by the claimant or the law whose aid he invokes in the exercise of his right. I have the duty of paying my debt, but I have no right to thrust the owed coppers (say) into the pocket of an unwilling creditor. The duty of taking spiritual message is performed by the messenger becoming a fit vehicle by prayer and fasting. Conceived as a right, it may easily become an imposition on unwilling parties.

Thus the manifesto, undoubtedly designed to allay suspicion and soothe the ruffled feelings of Hindus, in my opinion, fails to accomplish its purpose. On the contrary, it leaves a bad taste in the mouth. I venture to suggest to the authors that they need to reexamine their position in the light of my remarks. Let them recognize the fundamental difference between rights and duties. In the spiritual sphere, there is no such thing as a right.

1. The heading of the manifesto was. "Our Duty to the Depressed and Backward Classes".

Note: The signatories were: K.K. Chandy, S. Gnanaprakasam, S. Gurubatham, S. Jesudasen, M. P. Job, G. Joseph, K.I. Matthai, A. A. Paul, S.E. Ranganadham, A.N. Sudarsanam, O. F.E. Zacharia, D.M. Devasahayam, G.V. Martyn.

1.Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Perspectives and Encounters/ Harold Coward

2.Christians and Public Life in Colonial South India, 1863-1937: Contending with Marginalty/ Chandra Mallampalli