The Sino-Indian Treaty on Relations between India and the Tibet Region of China was signed in 1954. India gave up its rights in Tibet without seeking a quid pro quo. The Panch Sheel was enunciated,which Jawaharlal Nehru presumed presupposed inviolate boundaries in an era of Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai.

The young Dalai Lama ( then 26) came to India in 1956 to participate in the 2500th anniversary celebrations commemorating the Enlightenment of the Buddha but was reluctant to return home as he felt China had reneged from its promise of Tibetan autonomy. Chou En-lai visited India later that year and sought Nehru’s good offices to persuade the Dalai Lama to return to Lhasa on the assurance of implementation of the 17 Point Agreement by China in good faith.

Visiting China in 1954, Nehru drew Chou En-lai’s attention to the new political map of India which defined the McMahon Line and the J&K Johnson Line as firm borders (and not in dotted lines or vague colour wash as previously depicted) and expressed concern over corresponding Chinese maps that he found erroneous. Chou En-lai replied that the Chinese had not yet found time to correct its old maps but that this would be done “when the time is ripe”. Nehru assumed this implied tacit Chinese acceptance of India’s map alignments but referred to the same matter once again during Chou’s 1956 visit to India.

The Aksai Chin road had been constructed by China by 1956-57 but only came to notice in 1958 when somebody saw it depicted on a small map in a Chinese magazine. India protested. The very first note in the Sino-Indian White Papers, published later, declared Aksai Chin to be “indisputably” Indian territory ” and, thereafter, incredibly lamented the fact that Chinese personnel had wilfully trespassed into that area “without proper visas”.The misguided Nehru was even at that time prepared to be flexible and negotiate a peaceful settlement or an appropriate adjustment. Parliament and the public were, however, kept in the dark.

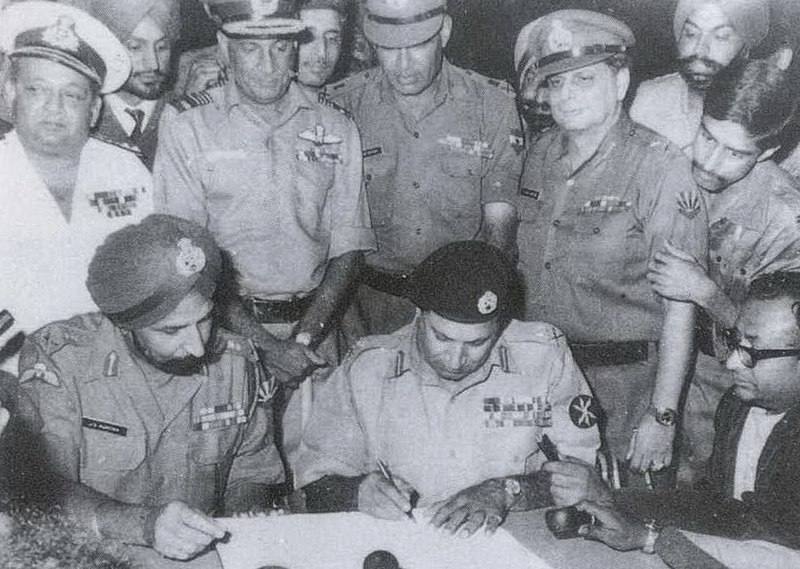

|

| Menon and Nehru |

Nehru had begun to reassess his position.The late G. Parthasarathi met Nehru on the evening of 18 March 1958, after all concerned had briefed him prior to his departure for Peking as the new Indian Ambassador to China. GP recorded what Nehru said:

“So G.P. what has the Foreign Office told you? Hindi-Chini bhai bhai? Don’t you believe it! I don’t trust the Chinese one bit. They are a deceitful opinionated, arrogant and hegemonistic lot. Eternal vigilance should be your watch word. You should send all your Ttelegrams only to me – not to the Foreign Office. Also, do not mention a word of this instruction of mine to Krishna ( Menon). He, you and I all share a common world view and ideological approach. However, Krishna believes – erroneously – that no Communist country can have bad relations with any Non-Aligned country like ours”.

Chinese incursions and incidents at Longju and Khizemane in Arunachal and the Kongka Pass, Galwan and Chip Chap Valleys in Ladakh followed through 1959. The Times of India broke many of these early stories.Vague whispers of “some trouble” further east were heard.On the way to Chushul, the air strip was still open,and beyond to the Pangong Lake unimpeded.

The Khampa rebellion in Tibet had erupted and the Dalai Lama fled to India in 1959 via Tawang where he received an emotional welcome. The Government of India granted him asylum along with his entourage and over 100,000 refugees that followed and he took up residence with his government-in-exile in Dharamsala. These events disturbed the Chinese and marked a turning point in Sino-Indian relations. Their suspicions about India’s intentions were not improved by Delhi’s connivance in facilitating CIA-trained Tibetan refugee guerrillas to operate in Tibet and further permitting an American listening facility to be planted on the heights of Nanda Devi to monitor Chinese signals in Tibet.

China had by now commenced its westward cartographic-cum-military creep in Ladakh and southward creep in Arunachal.

The highly respected Chief of Army Staff, Gen.K.S. Thimayya began to envisage a new defence posture vis-à-vis China in terms of plans, training, logistics and equipment.Krishna Menon, aided by B.N. Mullick, the IB Chief , who also was close to Nehru, disagreed with this threat perception and insisted that attention should remain focussed on Pakistan and the “anti-Imperialist forces”. Growing interference by Krishna Menon, now Defence Minister, in Army postings and promotions and strategic perspectives so frustrated Thimayya that he tendered his resignation to Nehru in 1959. Fearing a major crisis, the PM persuaded Thimayya to withdraw his resignation, which he unfortunately did at the cost of his authority. Nothing changed. Mullick and Menon sowed in Nehru’s mind the notion that a powerful Chief might stage a coup (as Ayub had done). This myth was for long a factor in Government’s aversion to the idea of appointing a Chief of Defence Staff.

A coup had taken place the previous year in October 1958 in neighbouring Pakistan, and there was loose talk in the cocktail party circuit of whether India’s turn would be next. A naturally paranoid defence minister would have found all this sinister, even though the Times of India of 4 January 1959 carried this report:

No Possibility of Military ‘Coup’ in India

Ruling out the possibility of a military ‘coup’ in India, Mr. V.K. Krishna Menon, Defence Minister, said here today that ‘whosoever attempted such a thing would come to grief . . .’ Mr. Menon said:

"We have a strong parliamentary system of Government. Our soldiers are well educated and disciplined. They do not meddle in politics.’ ‘In fact’, Mr. Menon added, ‘it is silly to think in terms of a military dictatorship’. ‘The people’, he said, ‘were conscious of their democratic rights and the prevailing social conditions widely varied from what led to military regime in other countries . . ."

Mountbatten had been pressing both Nehru and Krishna Menon to appoint a chief of defence staff (CDS) who would have overarching authority over the army, navy and air force, and had been suggesting Thimayya’s name for this post. Krishna Menon resented this lobbying and, in any case, was dead set against the idea of a CDS, thinking that it would give too much importance in policy to a single military man.

It was with pain and anguish Gen Thimayya described to other senior officers, the relations of the Army HQs with the Defense Ministry; mainly his with the Defense Minister, VK Krishna Menon.

No wonder the Indian Army got the thrashing of its life from the Chinese, just three years later in 1962. And within two years of that Nehru died a broken and ravaged man. Here is how the story of General Thimayya’s resignation:

Menon called Thimayya and told him that he had no business to meet the Prime Minister without his specific approval. Thimayya reiterated that the Prime Minister desired to know about the preparedness and the state of morale of the Army and he had told him nothing that he had, over the period of 18 months or so, not discussed with the Minister.

Menon remained furious and said: “No, General. It’s downright disloyalty and amounts to impropriety.”

To this, Thimayya replied,: “I make no allegations. You can call the other Chiefs too. They will say the same that they and I have continuously said — that the Services are being neglected and that their morale is low. These are the facts that we have told you earlier and I told the Prime Minister now. I am reiterating that by speaking candidly I and other Chiefs are being loyal to you, the Government and to the Country. That’s what loyalty means to me.”

It was with pain and anguish Gen Thimayya described to other senior officers, the relations of the Army HQs with the Defense Ministry; mainly his with the Defense Minister, VK Krishna Menon.

No wonder the Indian Army got the thrashing of its life from the Chinese, just three years later in 1962. And within two years of that Nehru died a broken and ravaged man. Here is how the story of General Thimayya’s resignation:

Menon called Thimayya and told him that he had no business to meet the Prime Minister without his specific approval. Thimayya reiterated that the Prime Minister desired to know about the preparedness and the state of morale of the Army and he had told him nothing that he had, over the period of 18 months or so, not discussed with the Minister.

Menon remained furious and said: “No, General. It’s downright disloyalty and amounts to impropriety.”

To this, Thimayya replied,: “I make no allegations. You can call the other Chiefs too. They will say the same that they and I have continuously said — that the Services are being neglected and that their morale is low. These are the facts that we have told you earlier and I told the Prime Minister now. I am reiterating that by speaking candidly I and other Chiefs are being loyal to you, the Government and to the Country. That’s what loyalty means to me.”

After another outburst from Menon, Thimayya saw no further point in carrying on the conversation. Deeply hurt at the Minister’s remarks, he got up and repeated: “I have never been disloyal to anyone, least of all to you, my country or the government.”

Menon shouted at the top of his voice. “You are disloyal to me and I have no place for disloyal generals”.

After Thimaya left, Menon met Nehru, who asked him not to rock the boat. He assured him that he would once again get the chiefs’ willing co-operation, provided Menon showed patience.

It was late when Thimayya reached home and told his wife, Nina to be ready to pack up and then murmured, “It’s time to pack up honorably.” He also talked to the other Chiefs, Air Chief Marshal Mukherjee and Admiral Katari and told them he was seriously contemplating putting in his papers the next day. Both repeated their vow to ‘follow him.

It was late when Thimayya reached home and told his wife, Nina to be ready to pack up and then murmured, “It’s time to pack up honorably.” He also talked to the other Chiefs, Air Chief Marshal Mukherjee and Admiral Katari and told them he was seriously contemplating putting in his papers the next day. Both repeated their vow to ‘follow him.

| General Thimayya |

Thimayya drafted his resignation letter the following morning and showed it to Mukherjee and Katari, both of whom confirmed their willingness to follow suit. “My conscience says wait” was Nina’ s advice.

Thimaya called Major General S.P.P. Thorat, his preferred successor, who advised the same. So was the suggestion of Bogey Sen, his CGS and Wadalia, his Deputy Chief. General Cariappa who was in Delhi asked him to meet the prime minister again before he ‘bunged in’ his letter.

That night, Thimayya thought and re-thought about throwing away a fine career, the great honor the country had bestowed upon him and the trust his officers and men had reposed in him. It was one of the saddest nights of his life. In the morning Thimaya sent his letter to Nehru..

Nehru called Thimayya and put his arm around his shoulder and asked him why he hadn’t met him earlier, rather than sending in his resignation. “Please withdraw it straight away,” ordered a visibly annoyed Prime Minister. “I will see you again at 7 pm with your letter withdrawing your resignation. In the meanwhile, I am keeping your letter with me.” He then asked him to return at 7 pm.

Katari had informed Mukherjee, who was by now in London, that Thimayya had submitted his resignation and he was following suit. The period between 2.30 pm and 7 pm was used by Nehru to control the damage which the resignation of the chiefs would cause to the government, the services’ morale, and result in the joy of the enemy.

Nehru rang up Katari and told him that he had called Thimayya and he was withdrawing his resignation and he should not entertain any such proposal. (A similar message went to Mukherjee through the High Commission.) He told him that Thimayya would meet him again in the evening and he should meet him at 9.30 pm.

By the time Thimaya arrived at the Teen Murti residence of the prime minister at 7 pm through a carefully orchestrated game play, Nehru had distanced the other chiefs from Thimayya by talking them out of it. Menon too was asked to keep a draft of his resignation handy. An emergency meeting of the Cabinet Committee was also called.

When they met, Nehru began his effort to win over Timayya.Thimayya said that he had not changed his mind and instead urged the prime minister to accept his resignation. In his defense, he argued: “That’s the only honorable course left to me and the other chiefs. When professional advice and recommendations are flouted at the drop of a hat, the chief loses his place and importance.”

Nehru said: “We have sufficient problems. And at this moment of crisis, one should not do anything to encourage opponents and the enemy. Shouldn’t it be so, Timmy?"

Thimayya explained that it was indeed a “moment of crisis” and it was his loyalty to him and his sense of patriotism to the country that had moved him to sacrifice his job. He repeated that Menon as defense minister had “made it impossible” for him and the other chiefs to work as head of the services, and unless Menon was moved out of defense, there could be little progress. But he understood that as this obviously could not be agreed to by the prime minister, he — and the other chiefs — should step aside, and, therefore the submission of his resignation.

Nehru admitted that Menon was a “difficult man”, but he was simply “brilliant” and was doing service to defence which no one earlier had done. Thimaya agreed, but suggested that his methods of “man-management” were “outrageous” and his brilliance was that of an “Oxford professor of philosophy” rather than of a man dealing with the country’s defense forces which have to be prepared and motivated to fight enemies.

Thimaya called Major General S.P.P. Thorat, his preferred successor, who advised the same. So was the suggestion of Bogey Sen, his CGS and Wadalia, his Deputy Chief. General Cariappa who was in Delhi asked him to meet the prime minister again before he ‘bunged in’ his letter.

That night, Thimayya thought and re-thought about throwing away a fine career, the great honor the country had bestowed upon him and the trust his officers and men had reposed in him. It was one of the saddest nights of his life. In the morning Thimaya sent his letter to Nehru..

Nehru called Thimayya and put his arm around his shoulder and asked him why he hadn’t met him earlier, rather than sending in his resignation. “Please withdraw it straight away,” ordered a visibly annoyed Prime Minister. “I will see you again at 7 pm with your letter withdrawing your resignation. In the meanwhile, I am keeping your letter with me.” He then asked him to return at 7 pm.

Katari had informed Mukherjee, who was by now in London, that Thimayya had submitted his resignation and he was following suit. The period between 2.30 pm and 7 pm was used by Nehru to control the damage which the resignation of the chiefs would cause to the government, the services’ morale, and result in the joy of the enemy.

Nehru rang up Katari and told him that he had called Thimayya and he was withdrawing his resignation and he should not entertain any such proposal. (A similar message went to Mukherjee through the High Commission.) He told him that Thimayya would meet him again in the evening and he should meet him at 9.30 pm.

By the time Thimaya arrived at the Teen Murti residence of the prime minister at 7 pm through a carefully orchestrated game play, Nehru had distanced the other chiefs from Thimayya by talking them out of it. Menon too was asked to keep a draft of his resignation handy. An emergency meeting of the Cabinet Committee was also called.

When they met, Nehru began his effort to win over Timayya.Thimayya said that he had not changed his mind and instead urged the prime minister to accept his resignation. In his defense, he argued: “That’s the only honorable course left to me and the other chiefs. When professional advice and recommendations are flouted at the drop of a hat, the chief loses his place and importance.”

Nehru said: “We have sufficient problems. And at this moment of crisis, one should not do anything to encourage opponents and the enemy. Shouldn’t it be so, Timmy?"

Thimayya explained that it was indeed a “moment of crisis” and it was his loyalty to him and his sense of patriotism to the country that had moved him to sacrifice his job. He repeated that Menon as defense minister had “made it impossible” for him and the other chiefs to work as head of the services, and unless Menon was moved out of defense, there could be little progress. But he understood that as this obviously could not be agreed to by the prime minister, he — and the other chiefs — should step aside, and, therefore the submission of his resignation.

Nehru admitted that Menon was a “difficult man”, but he was simply “brilliant” and was doing service to defence which no one earlier had done. Thimaya agreed, but suggested that his methods of “man-management” were “outrageous” and his brilliance was that of an “Oxford professor of philosophy” rather than of a man dealing with the country’s defense forces which have to be prepared and motivated to fight enemies.

Finally, he told his prime minister: “With the present state of the army, I can hardly assure success. We are not prepared. All my efforts — as also of others — have failed for the past 24 to 30 months to make the armed forces a viable defense force. So let someone else do the job – I request my resignation be kindly accepted.”

Nehru then pleaded with Thimayya: “Timmy, I ask you to withdraw this resignation. I, as your elder and not necessarily your Prime Minister, am requesting you to do s o. I promise to restore dignity to you and the other Chief’s Offices. We have to fight an enemy. For my sake, withdraw it.”

At 9.30 pm Katari met Nehru who told him that they were “ganging up” against Menon and that “Thimayya had withdrawn his resignation” — both factually wrong. Katari, then decided to call off handing his letter of resignation without even checking with Thimayya.

Enormous damage was done to the Chiefs’ solid standing.

On the morning of 1 September, the Capital awoke alarmed to the disturbing disclosures in the Statesman about Thimayyas’ resignation (which had, by then, been withdrawn). J N Chaudhuri,a top army officer,who was the daily's confidential military commentator, had passed on the information.Chaudhuri would become Chief of the Army in November 1962.Chaudhuri would later admit in his autobiography to being the military correspondent of the Statesman from 1951 for a decade and confess that his ‘anonymity was very well kept’.

There was also considerable applause when the prime minister assured the House — and through it, the country — that “under our practice, the civil authority is, and must remain supreme” (while it should, however, pay due heed to expert advice). There was also applause when he referred to the army’s “fine mettle” and “excellent morale.”

It was (daughter) Mireille who wept bitterly at the public humiliation of her father in Parliament (where she sat alongside Indira Gandhi) by Pandit Nehru; tears welled up in her eyes. When she recalled the scene to her father, the tears returned.

She spoke of these things to her father on the telephone at Secunderabad where he had gone for the forth coming inauguration of the Joint Land Warfare School. “Daddy, you have been let down. Mummy was right in asking you not to withdraw your letter.”

Thimayya said nothing.

On his return to Delhi, he showed her the office copy of his letter of resignation that contained the gist of what had transpired between him and Nehru – besides the appeals from the prime minister to withdraw his letter.

“You’ll now on defend your father, I hope,” he said.

“Always passionately, Daddy,” replied Mireille.

“If these are trivial, then I know of no other important issues,” he told Nina, who was furious at the withdrawal and asked him to “re-resign” without a second thought, and expose the duo.

He told her that he had accepted the advice and the assurances of his Prime Minister and had withdrawn his resignation.“For, in a democracy, a resignation is the only constitutional safeguard to a service chief against incompetent, unscrupulous or ambitious politicians” .

“If these are trivial, then I know of no other important issues,” he told Nina, who was furious at the withdrawal and asked him to “re-resign” without a second thought, and expose the duo.

He told her that he had accepted the advice and the assurances of his Prime Minister and had withdrawn his resignation.“For, in a democracy, a resignation is the only constitutional safeguard to a service chief against incompetent, unscrupulous or ambitious politicians” .

A month after the Thimayya resignation episode, the UK high commissioner in India, Malcolm Macdonald, met General Thimayya on 6 October 1959 and sent back a report of their long conversation, which was largely on the India–China border question. Towards the end, the topic of the minister of defence came up and Macdonald wrote:

"General Thimayya said one of the great difficulties in all this business had been Mr. Krishna Menon’s zeal in representing the Pakistanis as the true enemies of India. Mr. Menon played up and often publicized as extremely unfriendly every small frontier trouble between the Pakistanis and Indians, invariably blaming the Pakistanis. The General did not know why the Minister did this. Perhaps it was because Mr. Menon wished to strengthen the case he had made (with popular effect for himself in India) against Pakistan over the Kashmir issue. Anyway, whatever the reason, the Minister of Defence insisted that India’s armed forces should be disposed on the assumption that an attack on India would be launched from Pakistan."

On his father's side, Thimayya belonged to the Kodendera clan of Kodagu to which India's first commander-in-chief General Cariappa also belonged (his uncle in fact).

General Thimayya had recommended Gen Thorat to succeed him as Gen Thorat had carried out a thorough recce and submitted a plan to Timmy in case of a war with China.

This was that since NO Roads had been made in the forward areas despite the urgings of Sardar Vallabhai Patel since 1950 and others thereafter, a classic Defensive Battle should be fought at the existing road heads so as to blunt the Chinese Offensive as then that would be from an extended advance over nebulous foot paths.

This recommendation was shelved and Gen Thapar was made Chief as a stop gap till Gen Kaul took over.

The press had barely returned to Tezpur on 17 November,when they learnt that the Chinese had mounted an attack on Se La and outflanked it as well.

Even as battle was joined, Kaul, disappeared from Tezpur to be with his men, throwing the chain of command into disarray. The saving grace was the valiant action fought at Walong in the Lohit Valley. Much gallantry was also displayed in Ladakh against heavy odds.

The use of the air force had been considered. Some thought that the IAF had the edge as its aircraft would be operating with full loads from low altitude air strips in Assam unlike the Chinese operating from the Tibetan plateau at base altitudes of 11,000-12,000 feet.The decision was to avoid use of offensive air power to prevent escalation.

On 18 November, word came that the Chinese had enveloped Se La, which

finally fell without much of a fight in view of conflicting orders. A day later the enemy had broken through to Foothills along the Kameng axis. Confusion reigned supreme. Kaul or somebody ordered the 4th Corps to pull back to Gauwahati on 19 November and, as military convoys streamed west, somebody else ordered that Tezpur and the North Bank be evacuated.

A “scorched earth” policy was ordered by somebody else again and the Nunmati refinery was all but blown up. The DM deserted his post. Rana KDN Singh, was directed to take charge of a tottering administration. He supervised the Joint Steamer Companies, mostly manned by East Pakistan lascars, as they ferried a frightened and abandoned civil population to the South Bank. The other modes of exodus were by bus and truck, car, cart, cycle and on foot. The last ferry crossing was made at 6 pm. Those who remained or reached the jetty late, melted into the tea gardens and forest.

The Indian Press had ingloriously departed the previous day, preferring safety to real news coverage, – as happened again in Kashmir in 1990, when at least women journalists subsequently redeemed the profession. Alongwith the two Indians remained in Tezpur, wandering around like lost souls, were some 10-15 patients who had been released from the local mental hospital.

Tezpur was a ghost town. The State Bank had burned its currency chest and a few charred notes kept blowing in the wind as curious mental patients kept prodding the dying embers. Some stray dogs and alley cats were the only other companions.

Around midnight, a transistor crackled to life as Peking Radio announced a unilateral ceasefire and pull back to the pre-October “line of actual control”, provided the Indian Army did not move forward.

Next morning, all the world carried the news, but AIR still had brave jawans gamely fighting the enemy as none had had the gumption to awaken Nehru and take his orders as the news was too big to handle otherwise.During the preceding days, everyone was tuned into Radio Peking to find out what was going on in our own country.

The Chinese officially admit to 2,419 casualties (722 dead and 1,697 wounded),if it is a solace for India.The figure is quite stunning, given the situation in which each Indian position was asked to fight.According to Chinese records, at no stage had there been any action that pitted more than an Indian infantry company against at least four to five times the number of Chinese troops.

Nehru was broken and bewildered. His letter to John F Kennedy seeking US military assistance after the fall of Bomdila was abject and pathetic. He feared that unless the tide was stemmed the Chinese would overrun the entire Northeast. He said they were massing troops in the Chumbi Valley and he apprehended another “invasion” from there. If Chushul was overrun, there was nothing to stop the Chinese before Leh.

The IAF had not been used as India lacked air defence for its population centres. He therefore requested immediate air support by 12 squadrons of all-weather supersonic fighters with radar cover, all operated by US personnel. But US aircraft were not to intrude into Chinese air space.

On 21 November, Lal Bahadur Shastri, the Home Minister, paid a flying visit on a mission of inquiry and reassurance. He was followed the next day by Indira Gandhi.

Nehru had meanwhile broadcast to the nation, and more particularly to “the people of Assam “to whom his “heart went out” at this terrible hour of trial. He promised the struggle would continue and none should doubt its outcome.

The administration returned to Bomdila only after a month. This it did under the Political Officer Maj K.C. Johorey just before Christmas.The people of NEFA had stood solidly with India and Johorey received a warm welcome.

Thapar had been removed and Gen J.N Chaudhuri appointed COAS. Kaul went into limbo. The Naga underground took no advantage of India’s plight. Pakistan had been urged by Iran and the US not to use India’s predicament to further its own cause and kept its word. But it developed a new relationship with China thereafter.

The US and the West had been sympathetic to India and its Ambassador, John Kenneth Galbraith, had a direct line to Kennedy.The US was also preoccupied with growing Sino-Soviet divide and the major Cuban missile crisis that boiled over in October 1962.

The COAS, Gen Choudhury ordered an internal inquiry into the debacle by Maj. Gen Henderson Brooks and Brigadier P.S Bhagat. The Henderson Brooks Report remains a top-secret classified document though its substance was leaked and published by Neville Maxwell who served as the London Times correspondent in India in the 1960s, became a Sinophile and wrote a critical book titled “India’s China War”. The Report brings out the political and military naiveté, muddle, contradictions and in-fighting that prevailed and failures of planning and command. There is no military secret to protect in the Henderson Brooks Report; only political and military ego and folly to hide.

In 1968, Brigadier John Dalvi, the former commanding officer of the 7th Infantry Brigade that participated in the 1962 Sino-Indian War authored a book named Himalayan Blunder, where he gave his first hand accounts and perceptions of the causes for India's defeat in the war. He was critical of Lt General B.M. Kaul and attributed the loss in 1962 war partly to him. Excerpt from the book: "He managed to keep himself away from hardship and learning the nuances of a military commander as a junior officer and later in service, managed to grab important Army senior command appointments due to his "pull". His involvement with Jawaharlal Nehru later turned out to be a major reason for shameful loss and massacre of Indian troops at the hands of the Chinese".

In 1991, K. Satchidananda Murty wrote a biographical book about the second President of India, S Radhakrishnan, named Radhakrishnan: His Life and Ideas. In the book, he quoted the former President as having expressed doubts over the capability of Lt General B.M. Kaul. Excerpt from the book: "The General Officer was well known in the Army and Political Circles to be a "personal favourite" of Jawaharlal Nehru since his junior officer days. He reportedly received a number of undue professional favours throughout his career due to this personal connection and he made full use of this opportunity with utter disregard to the Army organisation".

In the book The Unfought War of 1962: An Appraisal, by Raghav Sharan Sharma, he has mentioned that Lt General B.M. Kaul was a distant relation of Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. As a result,Krishna Menon who was the then Defence Minister and Jawaharlal Nehru's close aide, appointed Lt General B.M. Kaul as Chief of General Staff, against the recommendation of the outgoing Chief of Army Staff, General K.S.Thimayya and in spite of the fact that he was an Army Supply Corps officer, with no prior combat experience and having never commanded a fighting unit earlier.

Lt General Kaul also authored a book named The Untold Story, where he gave his version of reasons for the loss in the 1962 war.

As long as Congress was in power,India did not learn the lesson that borders are more important than boundaries and continued to neglect the development of Arunachal and North Assam lest China roll down the hill again.But at present, given the prevailing global and regional strategic environment and India’scurrent military preparedness, the debacle of 1962 will not be repeated.

After a quarter century later,after he laid down the office,during the Question Answer session at the end of Field Marshal Sam Maneckshaw's lecture at the Staff College given on Armistice Day, a question was asked:In the 1962 war, what was your appointment, were you in a position to do something about the situation?

Maneckshaw:In the 1962 war, I was in disgrace.

"I was Commandant of this Institution.Krishna Menon, the Defence Minister, disliked me intensely. General Kaul, who was Chief of General Staff at the time, and the budding man for the next higher appointment, disliked me intensely. So, I was in disgrace at the Staff College. There were charges against me – I will enumerate some of them – all engineered by Krishna Menon.

"I do not know if you remember that in 1961 or 1960, General Thimayya was the Army Chief. He had fallen out with Krishna Menon and had sent his resignation. The Prime Minister, Nehru, persuaded General Thimayya to withdraw his resignation. The members of Parliament disliked Krishna Menon and they went hammer and tongs for the Prime Minister in Parliament.

General Thimayya had recommended Gen Thorat to succeed him as Gen Thorat had carried out a thorough recce and submitted a plan to Timmy in case of a war with China.

This was that since NO Roads had been made in the forward areas despite the urgings of Sardar Vallabhai Patel since 1950 and others thereafter, a classic Defensive Battle should be fought at the existing road heads so as to blunt the Chinese Offensive as then that would be from an extended advance over nebulous foot paths.

This recommendation was shelved and Gen Thapar was made Chief as a stop gap till Gen Kaul took over.

President Ayub Khan of Pakistan had on a brief stopover meeting with Nehru in Delhi en route to Dhaka in 1959 had proposed “joint defence”. Joint defence against whom, was Nehru’s scornful and unthinking retort. Nehru was not unconscious of a potential threat from the north as he had from the early 1950s repeatedly told Parliament that the Himalayan rampart was India’s defence and defence line. He had somewhat grandiloquently and tactlessly proclaimed that though Nepal was indeed a sovereign nation, when it came to India’s security, India’s defence lay along the Kingdom’s northern border, Nepal’s independence notwithstanding! He had been remarkably lax in preparing to defend that not-quite-so-impenetrable a rampart or even countenance his own military from doing so.

Almost a decade later, Himalayan border road construction commenced under the Border Roads Organisation and forward positions were established. This Forward Policy, though opposed by Lt Gen.Daulat Singh, GOC-in-C Western Command, was pushed by Krishna Menon,de facto Foreign Minister, and equally by B.N Mullick, who played a determining role in these events, being present in all inner councils.

Many of the 43 new posts established in Ladakh were penny packets with little capability and support or military significance. The objective appeared more political, in fulfilment of an utterly fatuous slogan Nehru kept uttering in Parliament and elsewhere, that “not an inch of territory” would be left undefended though he had earlier played down the Aksai Chin incursion as located in a cold, unpopulated, elevated desert “where not a blade of grass grows”. In August Nehru announced that Indian forces had regained 2500 square miles of the 12,000 square miles occupied by the Chinese in Ladakh.

Backseat driving of defence policy continued to the end of Thimayya’s tenure when General P.N.Thapar was appointed COAS in preference to Thimayya’s choice of Lt. Gen S.P.P Thorat, Eastern Army Commander. Thorat had produced a paper in the prevailing circumstances advocating that while the Himalayan heights might be prepared as a trip-wire defence, NEFA should essentially be defended lower down at its waistwhich, among other things, would ease the Indian Army’s logistical and acclimatisation problems and correspondingly aggravate those of the Chinese. The Thorat plan, “The China Threat and How to Meet It”, got short shrift.

The Goa operation at the end of 1960 witnessed two strange events. The new Chief of General Staff (CGS), Lt. Gen. Brij Mohan Kaul marched alongside one of the columns of the 17th Division under Gen Kunhiraman Palat Candeth,( a Keralite like Menon), that was tasked to enter Goa. Thereafter he and, separately, the Defence Minister, Krishna Menon, declared “war” or the commencement of operations at two different times: one at midnight and the other at first light the next morning. In any other situation such flamboyant showmanship could have been disastrous.Goa was a cake walk and evoked the mistaken impression among gifted amateurs in high places that an unprepared Indian Army could take on China.

Kaul’s promotion to the rank of Lt. Gen and then to key post of CGS had stirred controversy,since he was a relative of Nehru. He was politically well connected and had held staff and PR appointments but was without command experience. The top brass was divided and the air thick with intrigue and suspicion. Kaul had inquiries made into the conduct of senior colleagues like Thorat, S.D Verma and then Maj.Gen. Sam Manekshaw, Commandant of the Staff College in Wellington.

Even as the exchange of Sino-Indian notes continued, Nehru on 12 October 1962 said he had ordered the Indian Army “to throw the Chinese out”, something casually revealed to the media at Palam airport before departing on a visit to Colombo.

A new 4 Corps was created on 8 October 1962 with headquarters at Tezpur to reinforce the defence of the Northeast. Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh was named GOC but was soon moved to take over 33 Corps at Siliguri and then moved again to the Western Command. Kaul took charge of 4 Corps but appeared to have assumed a superior jurisdiction because of his direct political line to Delhi. Command controversies were further compounded as at times it seemed that both everybody and nobody was in charge. Thapar himself and Gen L.P. Sen, at Eastern Command, also went to recce and reorder defence plans along the Bomdila-Se La sector. At the political level and at the External Affairs Ministry the adage was “Panditji knows best”.

Kaul was here, there and everywhere, exposing himself in high altitudes without acclimatisation.He fell ill and was evacuated to Delhi on 18 October only to return five days later.

Following Nehru’s “throw them out” order, and against saner military advice and an assessment of ground realities, a Brigade under John Dalvi was positioned on the Namka Chu River below the Thagla Ridge that the Chinese claimed lay even beyond the McMohan Line. It was a self -made trap. It was but to do or die. The Brigade retreated in disorder after a gallant action, while the Chinese rolled down to Tawang which they reached on 25 October.

The Economist parodied Rudyard Kipling. A text of a pithy editorial titled “Plain Tales from the Hills” read, “When the fog cleared, The Chinese were there”.

A new defence line was hurriedly established at Se La. Nehru was by now convinced that the Chinese were determined to sweep down to the plains. The national mood was one despondency, anger, foreboding. The Times of India editor, N.J.Nanporia, who sadly just passed away a few weeks ago, got it right.

In an edit page article he argued that the Chinese favoured negotiation and a peaceful settlement, not invasion, and India must talk. At worst the Chinese would teach India a lesson and go back. Critics scoffed at Nanporia. A week or 10 days later, in response to his critics, he

reprinted the very same article down to the last comma and full-stop. Events proved him absolutely right.

On 24 October, Chou En-lai proposed a 20 kilometre withdrawal by either side. Three days later Nehru sought the enlargement of this buffer to 40-60 km. On 4 November, Chou offered to accept the McMahon Line provided India accepted the Macdonald Line in Ladakh approximating the Chinese claim line (giving up the more northerly Johnson Line favoured by Delhi).

The Army arranged for the press to visit the NEFA front. On 15-17 November 15-17 all drove up to Se La (15,000 feet) and down to Dirang Dzong in the valley beyond before the climb to Bomdila.

Reporters saw Jawans in cottons and perhaps a light sweater and canvas shoes were manhandling ancient 25-pounders into position at various vantage points.They had seen and heard Brij Mohan Kaul’s theatrics and bravado at 4 Corps Headquarters a day earlier and were shocked to see the reality: ill-equipped, unprepared but cheerful officers and men digging in to hold back the enemy under the command of a very gallant officer, Brig Hoshiar Singh.

Almost a decade later, Himalayan border road construction commenced under the Border Roads Organisation and forward positions were established. This Forward Policy, though opposed by Lt Gen.Daulat Singh, GOC-in-C Western Command, was pushed by Krishna Menon,de facto Foreign Minister, and equally by B.N Mullick, who played a determining role in these events, being present in all inner councils.

Many of the 43 new posts established in Ladakh were penny packets with little capability and support or military significance. The objective appeared more political, in fulfilment of an utterly fatuous slogan Nehru kept uttering in Parliament and elsewhere, that “not an inch of territory” would be left undefended though he had earlier played down the Aksai Chin incursion as located in a cold, unpopulated, elevated desert “where not a blade of grass grows”. In August Nehru announced that Indian forces had regained 2500 square miles of the 12,000 square miles occupied by the Chinese in Ladakh.

Backseat driving of defence policy continued to the end of Thimayya’s tenure when General P.N.Thapar was appointed COAS in preference to Thimayya’s choice of Lt. Gen S.P.P Thorat, Eastern Army Commander. Thorat had produced a paper in the prevailing circumstances advocating that while the Himalayan heights might be prepared as a trip-wire defence, NEFA should essentially be defended lower down at its waistwhich, among other things, would ease the Indian Army’s logistical and acclimatisation problems and correspondingly aggravate those of the Chinese. The Thorat plan, “The China Threat and How to Meet It”, got short shrift.

The Goa operation at the end of 1960 witnessed two strange events. The new Chief of General Staff (CGS), Lt. Gen. Brij Mohan Kaul marched alongside one of the columns of the 17th Division under Gen Kunhiraman Palat Candeth,( a Keralite like Menon), that was tasked to enter Goa. Thereafter he and, separately, the Defence Minister, Krishna Menon, declared “war” or the commencement of operations at two different times: one at midnight and the other at first light the next morning. In any other situation such flamboyant showmanship could have been disastrous.Goa was a cake walk and evoked the mistaken impression among gifted amateurs in high places that an unprepared Indian Army could take on China.

Kaul’s promotion to the rank of Lt. Gen and then to key post of CGS had stirred controversy,since he was a relative of Nehru. He was politically well connected and had held staff and PR appointments but was without command experience. The top brass was divided and the air thick with intrigue and suspicion. Kaul had inquiries made into the conduct of senior colleagues like Thorat, S.D Verma and then Maj.Gen. Sam Manekshaw, Commandant of the Staff College in Wellington.

Even as the exchange of Sino-Indian notes continued, Nehru on 12 October 1962 said he had ordered the Indian Army “to throw the Chinese out”, something casually revealed to the media at Palam airport before departing on a visit to Colombo.

A new 4 Corps was created on 8 October 1962 with headquarters at Tezpur to reinforce the defence of the Northeast. Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh was named GOC but was soon moved to take over 33 Corps at Siliguri and then moved again to the Western Command. Kaul took charge of 4 Corps but appeared to have assumed a superior jurisdiction because of his direct political line to Delhi. Command controversies were further compounded as at times it seemed that both everybody and nobody was in charge. Thapar himself and Gen L.P. Sen, at Eastern Command, also went to recce and reorder defence plans along the Bomdila-Se La sector. At the political level and at the External Affairs Ministry the adage was “Panditji knows best”.

Kaul was here, there and everywhere, exposing himself in high altitudes without acclimatisation.He fell ill and was evacuated to Delhi on 18 October only to return five days later.

Following Nehru’s “throw them out” order, and against saner military advice and an assessment of ground realities, a Brigade under John Dalvi was positioned on the Namka Chu River below the Thagla Ridge that the Chinese claimed lay even beyond the McMohan Line. It was a self -made trap. It was but to do or die. The Brigade retreated in disorder after a gallant action, while the Chinese rolled down to Tawang which they reached on 25 October.

The Economist parodied Rudyard Kipling. A text of a pithy editorial titled “Plain Tales from the Hills” read, “When the fog cleared, The Chinese were there”.

A new defence line was hurriedly established at Se La. Nehru was by now convinced that the Chinese were determined to sweep down to the plains. The national mood was one despondency, anger, foreboding. The Times of India editor, N.J.Nanporia, who sadly just passed away a few weeks ago, got it right.

In an edit page article he argued that the Chinese favoured negotiation and a peaceful settlement, not invasion, and India must talk. At worst the Chinese would teach India a lesson and go back. Critics scoffed at Nanporia. A week or 10 days later, in response to his critics, he

reprinted the very same article down to the last comma and full-stop. Events proved him absolutely right.

On 24 October, Chou En-lai proposed a 20 kilometre withdrawal by either side. Three days later Nehru sought the enlargement of this buffer to 40-60 km. On 4 November, Chou offered to accept the McMahon Line provided India accepted the Macdonald Line in Ladakh approximating the Chinese claim line (giving up the more northerly Johnson Line favoured by Delhi).

The Army arranged for the press to visit the NEFA front. On 15-17 November 15-17 all drove up to Se La (15,000 feet) and down to Dirang Dzong in the valley beyond before the climb to Bomdila.

Reporters saw Jawans in cottons and perhaps a light sweater and canvas shoes were manhandling ancient 25-pounders into position at various vantage points.They had seen and heard Brij Mohan Kaul’s theatrics and bravado at 4 Corps Headquarters a day earlier and were shocked to see the reality: ill-equipped, unprepared but cheerful officers and men digging in to hold back the enemy under the command of a very gallant officer, Brig Hoshiar Singh.

|

| Dalai Lama,Nehru,Zhou En Lai |

The press had barely returned to Tezpur on 17 November,when they learnt that the Chinese had mounted an attack on Se La and outflanked it as well.

Even as battle was joined, Kaul, disappeared from Tezpur to be with his men, throwing the chain of command into disarray. The saving grace was the valiant action fought at Walong in the Lohit Valley. Much gallantry was also displayed in Ladakh against heavy odds.

The use of the air force had been considered. Some thought that the IAF had the edge as its aircraft would be operating with full loads from low altitude air strips in Assam unlike the Chinese operating from the Tibetan plateau at base altitudes of 11,000-12,000 feet.The decision was to avoid use of offensive air power to prevent escalation.

On 18 November, word came that the Chinese had enveloped Se La, which

finally fell without much of a fight in view of conflicting orders. A day later the enemy had broken through to Foothills along the Kameng axis. Confusion reigned supreme. Kaul or somebody ordered the 4th Corps to pull back to Gauwahati on 19 November and, as military convoys streamed west, somebody else ordered that Tezpur and the North Bank be evacuated.

A “scorched earth” policy was ordered by somebody else again and the Nunmati refinery was all but blown up. The DM deserted his post. Rana KDN Singh, was directed to take charge of a tottering administration. He supervised the Joint Steamer Companies, mostly manned by East Pakistan lascars, as they ferried a frightened and abandoned civil population to the South Bank. The other modes of exodus were by bus and truck, car, cart, cycle and on foot. The last ferry crossing was made at 6 pm. Those who remained or reached the jetty late, melted into the tea gardens and forest.

The Indian Press had ingloriously departed the previous day, preferring safety to real news coverage, – as happened again in Kashmir in 1990, when at least women journalists subsequently redeemed the profession. Alongwith the two Indians remained in Tezpur, wandering around like lost souls, were some 10-15 patients who had been released from the local mental hospital.

Tezpur was a ghost town. The State Bank had burned its currency chest and a few charred notes kept blowing in the wind as curious mental patients kept prodding the dying embers. Some stray dogs and alley cats were the only other companions.

Around midnight, a transistor crackled to life as Peking Radio announced a unilateral ceasefire and pull back to the pre-October “line of actual control”, provided the Indian Army did not move forward.

Next morning, all the world carried the news, but AIR still had brave jawans gamely fighting the enemy as none had had the gumption to awaken Nehru and take his orders as the news was too big to handle otherwise.During the preceding days, everyone was tuned into Radio Peking to find out what was going on in our own country.

1962 was a Nehru-Menon directed military disaster. President Radhakrishnan indicted the Government for its “credulity and negligence”. Nehru himself confessed, artfully using the plural, “We were getting out of touch with reality … and living in an artificial world of our own creation”.

He was reluctant to get rid of Krishna Menon, (making him, first, Minister for Defence Production and then Minister without Portfolio, in which capacity he brazenly carried on much as before). Public anger finally compelled the PM to drop him altogether or risk losing his own job.

He was reluctant to get rid of Krishna Menon, (making him, first, Minister for Defence Production and then Minister without Portfolio, in which capacity he brazenly carried on much as before). Public anger finally compelled the PM to drop him altogether or risk losing his own job.

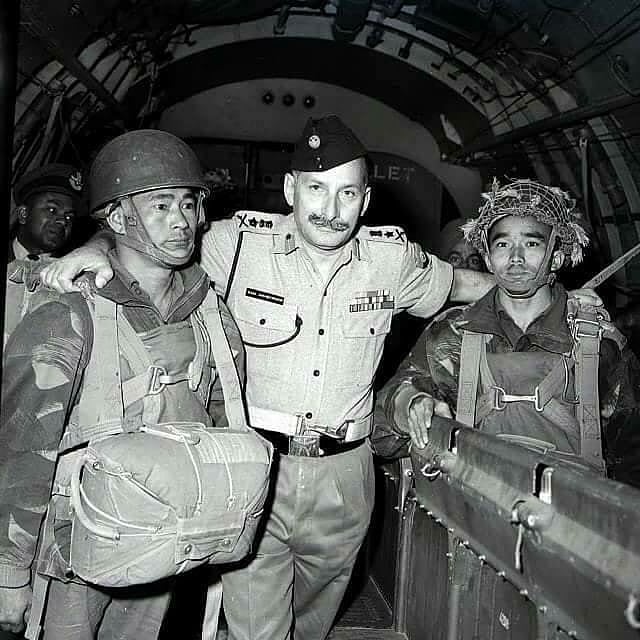

|

| Sam Maneckshaw |

Nehru was broken and bewildered. His letter to John F Kennedy seeking US military assistance after the fall of Bomdila was abject and pathetic. He feared that unless the tide was stemmed the Chinese would overrun the entire Northeast. He said they were massing troops in the Chumbi Valley and he apprehended another “invasion” from there. If Chushul was overrun, there was nothing to stop the Chinese before Leh.

The IAF had not been used as India lacked air defence for its population centres. He therefore requested immediate air support by 12 squadrons of all-weather supersonic fighters with radar cover, all operated by US personnel. But US aircraft were not to intrude into Chinese air space.

On 21 November, Lal Bahadur Shastri, the Home Minister, paid a flying visit on a mission of inquiry and reassurance. He was followed the next day by Indira Gandhi.

Nehru had meanwhile broadcast to the nation, and more particularly to “the people of Assam “to whom his “heart went out” at this terrible hour of trial. He promised the struggle would continue and none should doubt its outcome.

The administration returned to Bomdila only after a month. This it did under the Political Officer Maj K.C. Johorey just before Christmas.The people of NEFA had stood solidly with India and Johorey received a warm welcome.

Thapar had been removed and Gen J.N Chaudhuri appointed COAS. Kaul went into limbo. The Naga underground took no advantage of India’s plight. Pakistan had been urged by Iran and the US not to use India’s predicament to further its own cause and kept its word. But it developed a new relationship with China thereafter.

The US and the West had been sympathetic to India and its Ambassador, John Kenneth Galbraith, had a direct line to Kennedy.The US was also preoccupied with growing Sino-Soviet divide and the major Cuban missile crisis that boiled over in October 1962.

The COAS, Gen Choudhury ordered an internal inquiry into the debacle by Maj. Gen Henderson Brooks and Brigadier P.S Bhagat. The Henderson Brooks Report remains a top-secret classified document though its substance was leaked and published by Neville Maxwell who served as the London Times correspondent in India in the 1960s, became a Sinophile and wrote a critical book titled “India’s China War”. The Report brings out the political and military naiveté, muddle, contradictions and in-fighting that prevailed and failures of planning and command. There is no military secret to protect in the Henderson Brooks Report; only political and military ego and folly to hide.

In 1968, Brigadier John Dalvi, the former commanding officer of the 7th Infantry Brigade that participated in the 1962 Sino-Indian War authored a book named Himalayan Blunder, where he gave his first hand accounts and perceptions of the causes for India's defeat in the war. He was critical of Lt General B.M. Kaul and attributed the loss in 1962 war partly to him. Excerpt from the book: "He managed to keep himself away from hardship and learning the nuances of a military commander as a junior officer and later in service, managed to grab important Army senior command appointments due to his "pull". His involvement with Jawaharlal Nehru later turned out to be a major reason for shameful loss and massacre of Indian troops at the hands of the Chinese".

In 1991, K. Satchidananda Murty wrote a biographical book about the second President of India, S Radhakrishnan, named Radhakrishnan: His Life and Ideas. In the book, he quoted the former President as having expressed doubts over the capability of Lt General B.M. Kaul. Excerpt from the book: "The General Officer was well known in the Army and Political Circles to be a "personal favourite" of Jawaharlal Nehru since his junior officer days. He reportedly received a number of undue professional favours throughout his career due to this personal connection and he made full use of this opportunity with utter disregard to the Army organisation".

In the book The Unfought War of 1962: An Appraisal, by Raghav Sharan Sharma, he has mentioned that Lt General B.M. Kaul was a distant relation of Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. As a result,Krishna Menon who was the then Defence Minister and Jawaharlal Nehru's close aide, appointed Lt General B.M. Kaul as Chief of General Staff, against the recommendation of the outgoing Chief of Army Staff, General K.S.Thimayya and in spite of the fact that he was an Army Supply Corps officer, with no prior combat experience and having never commanded a fighting unit earlier.

Lt General Kaul also authored a book named The Untold Story, where he gave his version of reasons for the loss in the 1962 war.

As long as Congress was in power,India did not learn the lesson that borders are more important than boundaries and continued to neglect the development of Arunachal and North Assam lest China roll down the hill again.But at present, given the prevailing global and regional strategic environment and India’scurrent military preparedness, the debacle of 1962 will not be repeated.

After a quarter century later,after he laid down the office,during the Question Answer session at the end of Field Marshal Sam Maneckshaw's lecture at the Staff College given on Armistice Day, a question was asked:In the 1962 war, what was your appointment, were you in a position to do something about the situation?

Maneckshaw:In the 1962 war, I was in disgrace.

"I was Commandant of this Institution.Krishna Menon, the Defence Minister, disliked me intensely. General Kaul, who was Chief of General Staff at the time, and the budding man for the next higher appointment, disliked me intensely. So, I was in disgrace at the Staff College. There were charges against me – I will enumerate some of them – all engineered by Krishna Menon.

"I do not know if you remember that in 1961 or 1960, General Thimayya was the Army Chief. He had fallen out with Krishna Menon and had sent his resignation. The Prime Minister, Nehru, persuaded General Thimayya to withdraw his resignation. The members of Parliament disliked Krishna Menon and they went hammer and tongs for the Prime Minister in Parliament.

|

"The Prime Minister made the statement, “I cannot understand why General Thimayya is saying that the Defence Ministry interferes with the working of the Army. Take the case of General Manekshaw. The Selection Board has approved his promotion to Lieutenant General, over the heads of 23 other officers. The Government has accepted that.”

"I was the Commandant of the Staff College. I had been approved for promotion to Lieutenant General. Instead of making me a Lieutenant General, Krishna Menon levied charges against me.

There were ten charges, I will enumerate only one or two of them – that I am more loyal to the Queen of England than to the President of India, that I am more British than Indian. That I have been alleged to have said that I will have no instructor in the Staff College whose wife looks like an ayah. These were the sort of charges against me.

"For eighteen months my promotion was held back. An enquiry was made. Three Lieutenant Generals, including an Army Commander, sat at the inquiry. I was exonerated on every charge. The file went up to the Prime Minister who sent it up to the Cabinet Secretary, who wrote on the file, ‘if anything happens to General Manekshaw, this case will go will down as the Dreyfus case.’

"So the file came back to the Prime Minister. He wrote on it, “Orders may now issue”, meaning I will now become a Lieutenant General. Instead of that, Ladies and Gentleman, I received a letter from the Adjutant General saying that the Defence Minister, Krishna Menon, has sent his severe displeasure to General Manekshaw, to be recorded.

"I had it in the office where the Commandant now sits. I sent that letter back to the Adjutant General saying what Krishna Menon could do with his displeasure – very vulgarly stated. It is still in my dossier.

"Then the Chinese came to my help. Krishna Menon was sacked, Kaul was sacked and Nehru sent for me. He said, “General, I have a vigorous enemy. I find that you are a vigorous General. Will you go and take over?” I said, “I have been waiting eighteen months for this opportunity,” and I went and took over.

"So, your question was 1962, and what part did I play -, none whatsoever, none whatsoever. I was here for eighteen months, persecuted, inquisitions against me but we survive …."

Another sordid story which began when Gen Thimayya was Chief and Nehru’s blue eyed Defence Minister – Krishna Menon began to under cut and humiliate the Chief in order to pave the way for the rise of the Kashmiri ASC Gen BM Kaul – a distant cousin of the PM:

The Story starts when the Defence Minister visits Maj Gen Sam Manekshaw who was GOC 26 Division and tries to enlist him against his own Chief – Gen Thimayya. Sam of course refuses point blank and thereby begins to dig his own grave.

This is the cause de terre for the enquiry which was initiated against Sam a year or so later when he was Commandant of the Staff College.

The principle witness against Sam in the enquiry against him was a close colleague and friend – then Colonel,later Brigadier – Kim Yadav. Kim was, indeed, an outstanding officer, who was for a while, ADC to Lord Louis Mountbatten.

Years later when Sam took over Western Command where Brig Kim Yadav was Commanding a Brigade, Sam heard some officers in the Mess, in hushed tones belittling Brig Yadav. Turning to them he says, “Gentlemen, Brig Kim Yadav professionally is head and shoulders above most of you – all he lacks is character”.

At the end of the 1971 war, Kim Yadav sent a telegram to Sam, ‘You seem to have won the war all by yourself – without any help from me! My Congratulations’.

"I was the Commandant of the Staff College. I had been approved for promotion to Lieutenant General. Instead of making me a Lieutenant General, Krishna Menon levied charges against me.

There were ten charges, I will enumerate only one or two of them – that I am more loyal to the Queen of England than to the President of India, that I am more British than Indian. That I have been alleged to have said that I will have no instructor in the Staff College whose wife looks like an ayah. These were the sort of charges against me.

"For eighteen months my promotion was held back. An enquiry was made. Three Lieutenant Generals, including an Army Commander, sat at the inquiry. I was exonerated on every charge. The file went up to the Prime Minister who sent it up to the Cabinet Secretary, who wrote on the file, ‘if anything happens to General Manekshaw, this case will go will down as the Dreyfus case.’

"So the file came back to the Prime Minister. He wrote on it, “Orders may now issue”, meaning I will now become a Lieutenant General. Instead of that, Ladies and Gentleman, I received a letter from the Adjutant General saying that the Defence Minister, Krishna Menon, has sent his severe displeasure to General Manekshaw, to be recorded.

"I had it in the office where the Commandant now sits. I sent that letter back to the Adjutant General saying what Krishna Menon could do with his displeasure – very vulgarly stated. It is still in my dossier.

"Then the Chinese came to my help. Krishna Menon was sacked, Kaul was sacked and Nehru sent for me. He said, “General, I have a vigorous enemy. I find that you are a vigorous General. Will you go and take over?” I said, “I have been waiting eighteen months for this opportunity,” and I went and took over.

"So, your question was 1962, and what part did I play -, none whatsoever, none whatsoever. I was here for eighteen months, persecuted, inquisitions against me but we survive …."

Another sordid story which began when Gen Thimayya was Chief and Nehru’s blue eyed Defence Minister – Krishna Menon began to under cut and humiliate the Chief in order to pave the way for the rise of the Kashmiri ASC Gen BM Kaul – a distant cousin of the PM:

The Story starts when the Defence Minister visits Maj Gen Sam Manekshaw who was GOC 26 Division and tries to enlist him against his own Chief – Gen Thimayya. Sam of course refuses point blank and thereby begins to dig his own grave.

This is the cause de terre for the enquiry which was initiated against Sam a year or so later when he was Commandant of the Staff College.

The principle witness against Sam in the enquiry against him was a close colleague and friend – then Colonel,later Brigadier – Kim Yadav. Kim was, indeed, an outstanding officer, who was for a while, ADC to Lord Louis Mountbatten.

Years later when Sam took over Western Command where Brig Kim Yadav was Commanding a Brigade, Sam heard some officers in the Mess, in hushed tones belittling Brig Yadav. Turning to them he says, “Gentlemen, Brig Kim Yadav professionally is head and shoulders above most of you – all he lacks is character”.

At the end of the 1971 war, Kim Yadav sent a telegram to Sam, ‘You seem to have won the war all by yourself – without any help from me! My Congratulations’.

POST SCRIPT:

What we saw was a Prime Minister commanded by Mountbatten,even in 1959.He suggested Thimayya for the supreme post;Thimayya briefed everything to the British High Commissioner.An army Chief and an army General leaked secrets.Thus the army was in disarray and Nehru was the last British PM of India!

_____________________________

Reference:

1.A Chequered Brilliance: The Many Lives of V.K. Krishna Menon/Jairam Ramesh

2.1962: The War That Wasn't/ Shiv Kunal Verma

3.Dalvi, Brig. J.P.,Himalayan blunder – the curtain raiser to the Sino-Indian war of 1962

4.Kaul, Lt. Gen. B.M., "The untold story"

5.Maxwell, Neville, "India's China War"

4.Kaul, Lt. Gen. B.M., "The untold story"

5.Maxwell, Neville, "India's China War"

© Ramachandran