400 Chinese Soldiers Killed

That clash in Sikkim, where India got the better of China just five years after defeat in the 1962 war, saw more than 80 Indian soldiers killed while estimates say 400 Chinese soldiers may have been killed.

In 1967, India fought a battle against China to protect its land and won, according to a book. The 1967 battles of Nathu La and Cho La pass changed the Indo-China political dynamics forever. But no one speaks about this resounding victory.

In his book, ‘Watershed 1967: India’s forgotten victory over China’, army veteran Probal DasGupta explores the mystery.

“When you look at 1971, China didn’t interfere in the India-Pakistan war. Not many have asked that question as to why, but there are many reasons why 1967 is an important yet underrated reason why China did not go down the Siliguri corridor and cut India out. Thereafter, at various stand-offs, whether it is Daulat Beg Oldi or Doklam in 2017, India has always used that template and obtained a dominating position in stand-offs against China.”,he points out. “I think that has set the template and has also ensured, what I’ve maintained – that peace is obtained when you achieve parity. Hence, there was a parity that was obtained in 1967, which got back India’s pride and was also responsible in conveying to China that they’re militarily a bigger power and that they could not overrun India anymore,” adds Das Gupta.

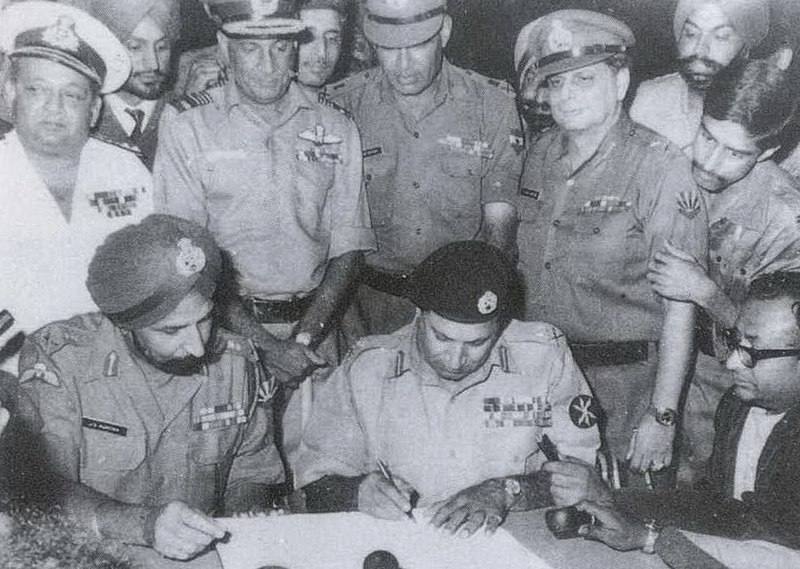

|

| Tensions during a standoff at the Sikkim border in 1967 |

Relations between India and China were already tense in 1967 but matters came to a head in August 1967. Irked by India’s decision to erect iron pickets along the border from NathuLa to Sebu La, the Chinese began to heckle Indian soldiers. What followed soon was a full blown clash with the Chinese attempting to wrest control over the Nathu La pass from India. A daring decision by the commanding officer, Lt General Sagat Singh stopped their plans from succeeding.

“As India was going up against Pakistan on the Western front, Chinese troops had amassed across the border near Sikkim, and that was the time when it was expected that Indian troops would pull back from Nathu-La. But General Sagat refused to do so because that would give the Chinese easy access to the Siliguri corridor down the Sikkim axis. Therefore, he disagreed with his superiors and stuck to his decision,” says Das Gupta.

Had General Sagat Singh not stood his ground, Chinese troops stationed at Nathu La would have captured the pass. This would give them easy access to the Siliguri corridor during the 1971 war. The outcome of the 1971 India-Pakistan could have then been very different.

“Psychologically, the political leadership was rattled and was even quite demoralised in 1962 as far as China was concerned. We had achieved some success against Pakistan in 1965. However, the overall attitude towards China was still very much different and defensive. Going against the grain of leadership was extremely creditable of General Sagat at that point of time,” Das Gupta records.

In the weeks and months ahead of the clash, the Indian side had decided to fence the border with three layers of barbed wire. Work started on August 20, 1967.

On August 23, about 75 Chinese in battle dress, carrying rifles fitted with bayonets, advanced slowly towards Nathu La in an extended line, and stopped at the border. The Political Commissar — identifiable by a red patch on his cap, and the only one who could speak some English — read out slogans from a red book, which the rest of the party shouted after him.

The Indian troops were “standing to”, watching and waiting. After about an hour, the Chinese withdrew. But they returned later, and continued their protests.

On September 5, as the barbed wire fence was being upgraded to a concertina coil, the Political Commissar had an argument with the Commanding Officer of the local infantry battalion, Lt Colonel Rai Singh. Thereafter, work stopped.

Work was, however, resumed on September 7. This provoked about 100 Chinese soldiers to rush up, and a scuffle ensued. Beaten down by the Jats, the Chinese resorted to stone-pelting, and the Indians responded in kind.

On September 10, the Chinese sent across a warning through the Indian embassy: “The Chinese Government sternly warns the Indian Government: the Chinese Border Defence Troops are closely watching the development of the situation along the China-Sikkim boundary. Should the Indian troops continue to make provocative intrusions, the Indian Government must be held responsible for all the grave consequences.”

The corps commander had ordered the fence to be completed on September 11. That day, as work started, the Chinese came to protest, led by the Political Commissar. Lt Col Rai Singh went out to talk to them.

Suddenly, the Chinese opened fire, and Singh fell to the ground, injured.

Seeing their CO hit, the infantry battalion attacked the Chinese post. But they suffered heavy casualties, including two officers, who were both given gallantry awards. Soldiers in the open were mowed down by Chinese machine gun fire.

Taken aback by the strong Indian response, the Chinese threatened to bring in warplanes. When the Indians refused to back off, the Chinese news agency Xinhua denied these plans.

Having sent its message militarily, India, on September 12, delivered a note to the Chinese, offering an unconditional ceasefire across the Sikkim-Tibet border beginning 5.30 am on September 13. This was rejected, but the situation remained largely peaceful until the 14th.

On September 15, the Chinese handed over the bodies of Indian soldiers with arms and ammunition, saying they were acting in the interest of “preserving Sino-Indian friendship”.

On October 1, another skirmish erupted at Cho La, but the Indians again repulsed the Chinese.

On September 13, 1967, Indian deputy prime minister Morarji Desai, who was visiting the U.S., appeared on the “Today” show. The first five questions he was asked were about the “fighting up in Sikkim” – the reference was to the clashes that had taken place from September 11 at Nathu La and would continue till September 14.

During the 1965 India-Pakistan war, there had been Chinese pressure on India, but the Nathu La fighting was seen as the first major clash between China and India since the 1962 war. And that war shaped how the Sikkim clashes were seen within and outside government in the U.S. In particular, it meant a focus on two aspects of the clashes – first, the likelihood of escalation and, second, Indian preparation and performance.

Asked about heightened Chinese rhetoric and warnings, Desai assessed, “They are mainly angry about the fact that we are not submitting to their pressures and their bullying…They would like us to fall in line with their strategy or their policy of dominating Asia and, ultimately, the world, as I see it.”

The 1962 war had been a major setback – in both geopolitical and psychological terms – to this strategy, as well as to how India was seen globally, regionally and within the U.S. That war, and setbacks related to Indian economic development and food supply, had shifted the American emphasis from the need to build up India to the need to prevent it from falling. Given this objective, any escalation on the China-India front was seen as potentially having consequences for Indian security and economic development – including by leading to even greater defense spending at the expense of development – and, potentially, requiring greater American involvement.

Thus, the U.S. government kept a close eye on the Sikkim clashes. American intelligence assessments had observed a deterioration of the China-India relationship, with a worsening of Chinese actions and words vis-à-vis India throughout 1967 amid the Cultural Revolution. Along with attacks on and expulsions of Indian diplomats, there had been numerous articles in People’s Daily in praise of the Naxalites, and Naga and Mizo insurgents, and calling for revolution in India. There had also been Chinese military probes into Bhutanese territory that summer. The Central Intelligence Agency indeed later saw the September clashes as “military expressions of intensified political relations.”

During the Nathu La clashes, American officials received updates through various means, including discussions with Indian officials. American and Indian military and diplomatic officials exchanged assessments in Delhi, Washington and Calcutta, including perplexity about Chinese motivations. Indian officials stated that they believed Chinese actions were localized, but deliberate.

The CIA director asked his staff for better reporting on the Sino-Indian border situation. Updates on the clashes made President Johnson’s daily brief each day between September 12 and 15, and then again after a clash took place at Cho La on October 1.

Officials particularly watched the scale of the clashes, the anti-India protests and propaganda campaign coming from China, whether Chinese logistical capabilities had been increased in the area, and Chinese troop dispositions not just at the point of the clashes, but also all along the border.

When the clashes ended, American Embassy officials reported back that “Indians confident they had the best of the incident.” There was a sense of relief within the U.S. government and outside – not just that the clashes had remained limited, but also with regard to how India performed both militarily and diplomatically. Noting that, unlike 1962, Delhi had not engaged in a war of words, The New York Times had indeed approvingly commented on Delhi’s demonstration of “firmness and restraint.” Press reporting on the incident had noted assessments that the clashes would remain limited, but there had simultaneously been concern that the 1962 war had been preceded by just such incidents and also that major Chinese offensives had followed lulls.

There was also an acknowledgement in the media, however, that India was better prepared than five years before. Finally, there was speculation about China’s motives, but also assessments that, whatever they were, they would have the consequences of weakening any voices in India calling for improved relations with China, “speed[ing] India’s movement toward cooperation with other nations of Asia in some kind of anti-Chinese front,” and strengthening those calling for India to develop nuclear weapons.

|

| Pak surrender 1971;Standing third is Sagat Singh |

This wasn’t just the assessment of external analysts. Intelligence briefings to members of Congress noted that Sino-Indian border incidents would be ongoing and “could flare up at any time.” There was a sense, however, that China was unlikely to attack in a major way at that time and more confidence in India’s capabilities. But there was also a concluding assessment: that the clashes would do nothing to ease Indian concerns about China and, in particular, “growing Indian fear of Chinese nuclear capabilities could eventually force India to build its own bomb.”

In his answers to the Today show interviewer, Desai tried to reassure the audience on both these fronts. He noted that Chinese behaviour could not be predicted, but said he expected the fighting would remain localized. Noting that India had been preparing and could defend itself, he asserted that India would not succumb to pressure.

In October 1967, another clash at Cho La ended in a similar manner as the one in Nathu La. Gorkhas and Grenadier troops of Indian Army demolished Chinese PLA forces in these battles. At least 88 Indian soldiers and over 340 Chinese troops lost their life in the battles and over a thousand were injured.

DasGupta believes that it was the right kind of political and military leadership of officers like General Sam Manekshaw and General Sagat that made the difference in the battles of 1967.

Probal DasGupta attributes multiple reasons why the battles of 1967 were forgotten.

“It was an era when India had suffered reverses a few years before that. Five years before that, in the 1962 India-China war, India had suffered a heavy setback. So, when this happened, it wasn’t covered as much in the media and people couldn’t really come to terms with what had happened there.”

Secondly, it was also because India and China had kind of not wanted to play it up as much. So, I think tacitly it was agreed to not play it up in the international fora. Thirdly, the most important reason was in 1971 when India had registered a resounding victory which whitewashed a lot of things that had happened in the past.”

Pointing that history shapes a narrative, DasGupta said, “The history of 1962 was written by Brigadier John Dalvi, who was the commander of the 7th Brigade, one of the first Indian brigades to be defeated by Chinese forces. Brigadier Dalvi was taken prisoner and he was kept in China for some time. After he came back, he wrote a book. It was bitter and explosive, but we banned the book.”

“Thereafter, Neville Maxwell wrote a book on India and China; it was sympathetic to China. What happened with that is when Henry Kissinger went to China in 1970-71, he visited Beijing and he met Zhou Enlai, and Zhou Enlai gave him that book as a gift. Henry Kissinger’s drift on China and his entire anti-India narrative was based heavily from his learnings from the book, which he found to be extremely impressive. So this is what history does. History does shape a narrative,” he added.

If it is true that 1967 marked the last major fighting that saw casualties on both sides, it was not, however, the last incident of a shot being fired on the contested boundary.

That would happen eight years later, when a patrol of Assam Rifles jawans was ambushed by the Chinese at Tulung La in Arunachal Pradesh. Four were killed.

The Indian government maintained that the Chinese had crossed the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and ambushed the patrol on October 20, 1975. The Chinese denied this and blamed India for the incident.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing accused the patrol of crossing the LAC and firing at a Chinese post. The Ministry handed a protest note on October 22 to the Charge d’Affaires of the Indian embassy in Beijing describing China’s actions as “a self defence response”, according to a November 3 report in the French newspaper Le Monde.The report said India recovered their bodies a week later on October 28.

A U.S. State Department cable from 1975 noted India’s view that the “Chinese ambush was sprung 500 metres south of Tulung La” and took place on Indian territory. It quoted a senior Indian military intelligence officer as saying on November 5 the border there was very clear, marked by a distinctive shale cliff. He said China had moved up a company to the pass and detached a platoon which erected stone walls on India’s side of the pass, and from there fired several hundred rounds at the patrol. Four of the patrol had gone into a leading position, while two others, who escaped, had stayed behind. The officer said the patrol was routine and had been in the area several times before.

The Indian government maintained that the Chinese had crossed the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and ambushed the patrol on October 20, 1975. The Chinese denied this and blamed India for the incident.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing accused the patrol of crossing the LAC and firing at a Chinese post. The Ministry handed a protest note on October 22 to the Charge d’Affaires of the Indian embassy in Beijing describing China’s actions as “a self defence response”, according to a November 3 report in the French newspaper Le Monde.The report said India recovered their bodies a week later on October 28.

A U.S. State Department cable from 1975 noted India’s view that the “Chinese ambush was sprung 500 metres south of Tulung La” and took place on Indian territory. It quoted a senior Indian military intelligence officer as saying on November 5 the border there was very clear, marked by a distinctive shale cliff. He said China had moved up a company to the pass and detached a platoon which erected stone walls on India’s side of the pass, and from there fired several hundred rounds at the patrol. Four of the patrol had gone into a leading position, while two others, who escaped, had stayed behind. The officer said the patrol was routine and had been in the area several times before.

The cable noted that Tulung La was among the more remote passes in the region, a few dozen kilometres from Bum La and Tawang. It noted China had used the pass during the 1962 war as a channel to send its troops down to Bomdi La, to defeat the Indian resistance there to their offensive.

“Although the Chinese appear to be following their policy of enforcing the status quo with respect to the LAC pending negotiations,” the cable concluded, “they apparently still lay claim to Arunachal Pradesh down to the

foothills”.

“Although the Chinese appear to be following their policy of enforcing the status quo with respect to the LAC pending negotiations,” the cable concluded, “they apparently still lay claim to Arunachal Pradesh down to the

foothills”.

The Hero of 1962

Singh was born in the village of Kusumdesar (Moda) in Churu district of Rajasthan.He joined Dungar College at Bikaner but was enrolled as a Naik in Bikaner Ganga Risala after his intermediate exam in 1938. Later, he was promoted to Jemadar (now called Naib Subedar) and commissioned as a Second lieutenant in Bikaner Ganga Risala which was sent to Sind in 1941 to deal with the Hoor rebellion. Later it was sent to Jubair in Iraq and Ahwaz in Iran during the war. He was selected for the 12th War Staff course at Quetta from May to November 1945.

On amalgamation of the State Forces in 1950, he joined Third Gorkha Rifles. He commanded the Second and Third Battalions of the Third Gorkha Rifles. In September 1961, he was promoted to the rank of brigadier and posted as the brigade commander of India's only parachute brigade, the 50th Parachute Brigade. The parachute brigade led by him played a prominent part in liberation of Goa, and his men were the first to enter Panjim on 19 December 1961.

|

| Sagat Singh |

He also played a pivotal role in counter-insurgency operations in Mizoram. For his distinguished services, the general officer was awarded the Param Vishisht Seva Medal . In December 1970, he took over the command of HQ IV Corps as a lieutenant general. The corps made the famous advance to Dhaka over the River Meghna during Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. He witnessed in Dhaka the signing of the surrender instrument by General Niazi.

For his leadership and command for the race to Dhaka, the Government of India honored Lt. Gen. Sagat Singh with the third highest civilian award of Padma Bhushan. Lt. Gen. Sagat Singh is the only other Corps commander besides Lt. Gen. (later Gen. and COAS) T N Raina and Lt. Gen. Sartaj Singh to be so awarded in 1971.

Sagat Singh died at the Army Hospital Research & Referral, New Delhi on 26 September 2001.Lt Gen Sagat Singh's character was played by Bollywood actor Jackie Shroff in the 2018 Indian Hindi-language film Paltan.

Dalvi's Book, Himalayan Blunder

Himalayan Blunder was an extremely controversial war memoir penned by Brigadier John Dalvi. It dealt with the causes, consequences and aftermath of the Sino-Indian War of 1962, that ended in Chinese People's Liberation Army inflicting a defeat on India.

The title seems to allude to the "Himalayan miscalculation" that Gandhi discusses in his autobiographical article for 14 April 1919, and which retained this title as Chapter 33 in Gandhi's autobiography.He had used the expression first at Nadiad.

Brigadier Dalvi served in the Indian Army and gives a first-person account of the war. The book was banned by the Indian Government after its publication.

Because of the book, the term "Himalayan blunder" came to be used as a synonym for colossal failure in the context of Indian politics.

The book begins with the narration of Brig. Dalvi's days in the DSSC, Wellington. He narrates an incident where a guest faculty, a retired British official, after hearing that Nehru had signed Panchsheel agreement with China in April 1954 and had decided to give up the post in Tibet that the British had maintained in Tibet to check Chinese advance, interrupted his class and warned that India and China would soon be at war and people in this class would be fighting it. Brig. Dalvi remembers that he was very angry with the gentleman questioning the authority of the gentleman to criticise the leader of his country.

|

1.Aksai Chin in the northeastern section of Ladakh District in Jammu and Kashmir.

2. British-designated North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), which is the present-day state of Arunachal Pradesh.

When the war broke out on 8 September 1962, Nehru was away from India. The Chinese attacked simultaneously on the Ladakh area and NEFA. They managed to capture 11,000 km² of area in Aksai Chin and substantial area in NEFA. The commander of IV Corps, Nehru's relative,General Brij Mphan Kaul was not on the front lines and was in Military Hospital, Delhi, recovering from an illness. Dalvi further alleges that B.M. Kaul was promoted to the position of General supplanting more capable, and senior officers because he was personally close to Nehru.

According to Dalvi, the Indian Army lacked leadership, equipment for mountain warfare, weaponry, and basic essentials like warm clothing, snow boots, and glasses. Brg Dalvi lavishes praise on his brigade's courage, bravery, and grit in face of superior opposition. Despite gaining territory, the Chinese army declared a unilateral ceasefire, while still maintaining the status quo. Brig. Dalvi was taken as prisoner of war along with the soldiers of his brigade. He was subsequently imprisoned for six months. Dalvi also records how China had meticulously planned the attack while officially it maintained a different posture.

Dalvi also examines the aftermath of the war. The detractors of Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru held Defence Minister Krishna Menon and General B M Kaul responsible for the debacle and both of them resigned.

Dalvi was born on 3 July 1920 in Basra, Iraq where his father was serving with the British administration. He returned to India in 1923 and studied at St. Mary's High School, Bombay. He graduated and joined to study under the Jesuits at St. Xavier's College, Bombay. In 1940 with the outbreak of World War II he joined Indian Army.

Dalvi was commissioned into the Baluch Regiment. To the end of World War II he served with the regiment's 5th Battalion. He took part in Field Marshal Sir William Slim's pursuit of Japanese Army. From October 1944 to March 1945 he saw fighting with 19th Indian Division notably at the Crossing of the Irrawaddy.

In 1945 he was selected to join the staff of General Sir Montagu Stopford, GOC XXXIII Corps and later GOC-in-C of 12th Army Burma.

In 1947 he was posted as instructor to Indian Military Academy, Dehradun. He was then moved to 5 Gorkha Rifles as 2nd in command. In 1949 Dalvi was attached with Brigade of the Guards. In 1950, he was selected for Staff College, which he graduated in 1951. He then commanded the 4th Battalion, Brigade of the Guards and later 2nd Guards.

In October 1960 he was given an accelerated promotion to be appointed as Brigadier Administration to XV Corps. In January 1962, he was given the Command on 7th Infantry Brigade in NEFA and fought in the Sino-Indian War. He was taken Prisoner of War on 22 October 1962 and was repatriated in May 1963.

On his return to India, he authored the book about the 1962 war, titled The Himalayan Blunder: The curtain raiser to the Sino-Indian War of 1962.The book was banned in Indian almost immediately on its release, but this ban was later lifted.His book is in direct contradiction with the book authored by his erstwhile commanding officer, Brij Mohan Kaul.In his book Brig. Dalvi bitterly described about his return to India:

We landed in Dum Dum airport in Calcutta on May 4, 1963. We were received cordially, appropriately. But the silence there was disquieting. I realized later. We had to prove we weren't brainwashed by Chinese ideology. We had to prove we were still loyal to India. My own army maintained a suspicious distance. The irony cannot be harsher: this treatment from a country, which for more than a decade had brainwashed itself into holding the Chinese baton wherever it went.

He died of cancer in 1980.

|

Military historian and film maker Shiv Kunal Verma's book,1962:The War That Wasn't speaks about a character called Bogey Singh.

Bogey Sen’s presence in Tawang between 22 and 23 October only added to the confusion. Before landing at Tawang, the army commander had flown towards Zimithang to get an idea of the terrain which he was not familiar with at all. Once in Tawang, as we have seen, Sen did nothing to bolster the confidence of the garrison. The meeting with [Lt Gen Niranjan] Prasad later in the evening focused on two issues: the Nam Ka Chu rout of 7 Brigade and the immediate withdrawal from Tawang. Bogey Sen opposing a withdrawal only amounted to theatrics, for had he wished, as the army commander, he had the authority to overrule Prasad.

Both officers at the time were unaware that Army HQ, now represented by Monty Palit, was pushing for the same decision. There was a critical difference though—Prasad was planning on falling back on Bomdila with Se-la only playing the part of a delaying obstacle. Palit, on the other hand, based on the one incomplete reconnaissance made almost two years ago, had made up his mind to dig in at Se-la. [Army chief Pran Nath] Thapar having gone along with his DMO, who now had the tacit approval of Nehru, was relegated to the role of a spectator. The Thorat Plan, even though it hadn’t been implemented, at least had had some discussions around it and plans had been drawn up. Just as Tawang was abandoned on a whim, Se-la was seemingly chosen arbitrarily by Monty Palit who played the ‘cleared by the cabinet’ card to ride roughshod over any opposition.

In the coming days, the Indian military high command would take decisions that lacked even the most basic common sense. Even as Palit was coming out of the defence minister’s room with Nehru’s ‘the military must decide where to fight’ mandate, Bogey Sen had decided to sack Niranjan Prasad as GOC 4 Division. Less than three hours previously, as he was leaving Tawang, Sen had eventually endorsed Prasad’s decision to pull back from Bum-la and evacuate Tawang. Surely, having seen for himself the effect of the headlong retreat from Zimithang on Prasad and other senior officers, Sen was experienced enough to know that to pull back any further would result in losing not just all the supplies and material that had so painstakingly been put together, but a withdrawal without a fight would further sap the morale of the men and officers. So far, after the first couple of hours of fighting on the Nam Ka Chu, Tsangdhar, Khenzemane, and Bum-la, all Indian units that had come into contact with the Chinese were only fighting in penny packets or withdrawing. Had it been decided that Tawang was to be held at all costs, it would have made perfect sense to replace Prasad as the GOC since the army commander felt he had lost the will to fight. But to institute this change after the withdrawal order was given was to add considerably to the existing chaos.

On the evening of 23 October neither Delhi, Lucknow nor Tezpur had any idea where the next defensive line was supposed to be; the only orders given until then were to abandon Tawang and Bum-la and fall back on Jang. When Palit took the draft of the order to hold Se-la to the chief, it was decided that Thapar, Palit and the IB chief, [B.N.] Mullik, would fly immediately to Tezpur and discuss the matter with Bogey Sen in person. From all indications,Thapar was still not fully convinced about the decision to hold Se-la. On his own initiative, Palit put into place steps for the stocking of supplies for Se-la, working on the assumption that five battalions would be required to hold the feature.

Who was Bogey Sen?

Lt General Lionel Protip "Bogey" Sen ( 1910 – 1981) commanded the Eastern Command during the Sino-Indian War of 1962. After the conflict, Sen was appointed GOC-in-C, Southern Command, on 10 May 1963.

Sen too wrote a book,Slender was the Thread:Kashmir Confrontation 1947-48.It has nothing on 1962.

A panicky Maharaja Hari Singh abandoned his efforts to somehow become independent, signed the Instrument of Accession to India, and the Army was ordered to save Srinagar and then evict the invaders.

India had very few troops in Kashmir then. The Maharaja’s state army had more or less collapsed. Its British chief left, the next in line killed by raiders close to Baramulla, Muslim troops defected and thousands of others just hid in fright.

|

| Bogey Sen |

There was a need to airlift troops to save Srinagar from falling. It had only a dirt airstrip. A brave airlift was set up with Dakotas filled with troops and equipment raising an incredible air-bridge between Delhi and Srinagar. The first brigade commander sent there, Brigadier J.C. Katoch, was wounded in the leg and had to be evacuated. A new Indian brigadier had to be found right away.

L.P. Sen, then a mere colonel, was the No. 2 in the Directorate of Military Intelligence under Brigadier P.N. Thapar (later Army chief in the 1962 war). General Sir Rob Lockhart, then India’s Chief of Army Staff, summoned Sen and ordered him to take over the defence of Srinagar and the Valley at once. Because he was still a colonel, he “promoted” him to brigadier temporarily, until Katoch recovered, “in 10 days or so”.

That was not to happen. Sen continued there for almost two years, defending Srinagar, liberating Baramulla, Uri, even Haji Pir Pass and linking it up with Poonch.He wrote his story in graphic detail in the first real military memoir by an Indian soldier post-Independence. There are controversies and questions about his claims.Sen claims in the book:

"As I was leaving General Russell’s house, I received a message to the effect that Brigadier Thapar would be waiting for me at the southern entrance to South Block of the Secretariat. When I arrived he informed me that Mahatma Gandhi wished to see me and be given an intelligence briefing. We drove to his residence and I told him everything that was known to us. He listened most intently and when I finished and asked whether he has any questions he would like answered, he replied “No, no questions.”

"After a few seconds of silence he continued, “Wars are a curse to humanity. They are so utterly senseless. They bring nothing but suffering and destruction.” As a soldier, and one about to be engaged in battle in a matter of hours, I was at a loss to know what to say, and eventually asked him: “What do I do in Kashmir?” Mahatma Gandhi smiled and said: “You’re going in to protect innocent people, and to save them from suffering and their property from destruction. To achieve that you must naturally make full use of every means at your disposal.” It was the last time I was to see him alive."

_____________

Photo ( top) Courtesy: Probal DasGupta

1.Dalvi, Brig. J.P., "Himalayan blunder – The Curtain Raiser to the Sino-Indian war of 1962

2.Kaul, Lt. Gen. B.M/The untold story

3.Maxwell, Neville, India's China War

Reference:

2.Kaul, Lt. Gen. B.M/The untold story

3.Maxwell, Neville, India's China War

4.Shiv Kunal Verma/1962:The War That Wasn't

© Ramachandran