He Had Captured Puli Thevar Too

“The mutiny in Meerut, which many claim as India’s first war of Independence, took place in 1857. However, almost a 100 years before that rebellion broke out, Marudhanayagam took on the British. To stop him, the British had to spend an amount that is almost on par with the amount that the US had to spend to vanquish Saddam Hussein in recent times",said Kamal Haasan on Marudhanayagam,while he was on a project on the so called hero.

Marudhanayagam,was Muhammad Yusuf Khan thoughout his mature life.So why the movie is titled Maruthanayagam?To appease the Hindus?

The British had his body dismembered and his body parts displayed on the principal gateways of the city of Madura for a while before despatching it to various other places as a warning to others who might harbour thoughts of rebellion against them.

Kamal had shot 30 minutes of the film and two hours were left.His then wife Sarika was the costume designer.But why Kamal shelved his dream project?As a political analyst,I infer that the movie,if made would be in hot waters,because Marudhanayagam,a Vellala Pillai,had got converted into Islam,and for long years in his life,he was Muhammad Yusuf Khan.He is not a hero of Hindus,neither of the Tamils.For people of Travancore,he was a brabarian,who looted the state every season.

His life is a contrast to the life of Chempaka Raman Pillai,the modern day anti British warrior,who never changed loyalities,unlike Marudhanayagam-It is better Kamal do a film on Chempaka Raman Pillai.

There are different accounts and versions on Marudhanayagam, but one of the most extensively researched accounts happens to be by an Englishman called Samuel Charles Hill.Hill, in his book on Marudhanayagam tilted Yusuf Khan, The Rebel Commandant, says Marudhanayagam was born a Hindu at Pannaiyur in Ramnad district and that he ran away from home as a boy. Later, he converted to Islam and took the name Muhammad Yusuf aafter which he seems to have entered the services of a couple of Europeans.

Yusuf seems to have rendered service, both as a military general and as an administrator. From the time he provided security to the convoys bringing supplies to the forts at Tirunelveli to the countless victories he won for the British, his services were ubiquitous. As a result, he was appointed Governor of Madurai and Tinnevelly. Yusuf Khan (1725 – 15 October 1764) or Maruthanayagam Pillai (correctly Mathuranayagam Pillai) was born in Panaiyur, Ramanathapuram District, Tamil Nadu, India in 1725. From humble beginnings, he became a warrior in the Arcot troops, later Commandant for the British East India Company troops. The British and the Arcot Nawab used him to suppress the Polygars (Palayakkarar) in the south of Tamil Nadu. Later he was entrusted to administrating the Madurai country when the Madurai Nayaks rule ended. Later a dispute arose with the British and Arcot Nawab, and three of his associates were bribed to capture Yusuf Khan; he was hanged in 1764 in Madurai.

The British had his body dismembered and his body parts displayed on the principal gateways of the city of Madura for a while before despatching it to various other places as a warning to others who might harbour thoughts of rebellion against them.

Kamal had shot 30 minutes of the film and two hours were left.His then wife Sarika was the costume designer.But why Kamal shelved his dream project?As a political analyst,I infer that the movie,if made would be in hot waters,because Marudhanayagam,a Vellala Pillai,had got converted into Islam,and for long years in his life,he was Muhammad Yusuf Khan.He is not a hero of Hindus,neither of the Tamils.For people of Travancore,he was a brabarian,who looted the state every season.

His life is a contrast to the life of Chempaka Raman Pillai,the modern day anti British warrior,who never changed loyalities,unlike Marudhanayagam-It is better Kamal do a film on Chempaka Raman Pillai.

There are different accounts and versions on Marudhanayagam, but one of the most extensively researched accounts happens to be by an Englishman called Samuel Charles Hill.Hill, in his book on Marudhanayagam tilted Yusuf Khan, The Rebel Commandant, says Marudhanayagam was born a Hindu at Pannaiyur in Ramnad district and that he ran away from home as a boy. Later, he converted to Islam and took the name Muhammad Yusuf aafter which he seems to have entered the services of a couple of Europeans.

|

| Yusuf Khan tomb |

Polygar (also spelled Palegara, Palaiyakkarar, Poligar, Palegaadu, Palegar, or Polegar, or Paalegaadu was the feudal title for a class of territorial administrative and military governors appointed by the Valmiki Nayaka rulers of Southern India (notably Vijayanagara Empire, Madurai Nayakas and the Kakatiya dynasty) during the 16th–18th centuries.

The Polygars of Madurai Country were instrumental in establishing administrative reforms by building irrigation projects, forts and religious institutions. The Polygars who worshipped the goddess Kali did not allow their territory to be annexed by Aurangzeb.

Their wars with the British East India Company after the demise of the Madurai Nayakas is often regarded as one of the earliest struggles for Indian independence. The British hanged many and banished others to the Andaman Islands. Dheeran Chinnamalai, Veerapandya Kattabomman, Maveeran Alagumuthu Kone, Puli Thevar, the Marudu brothers and Uyyalawada Narasimha Reddy were some notable Polygars who rose up in revolt against the British rule in Southern India. The war against the British forces predates the Indian rebellion of 1857 in Northern India.

Maruthanayagam Pillai (or Mathuranayagam Pillai) alias Yusuf Khan was born circa 1725 in a Hindu farming family of Saiva Vellalar caste.Being too restless in his youth, he left his native village, and converted to Islam. To make a living, he served as a domestic hand at the residence of the French Governor Monsr Jacques Law in Pondicherry. It was here he befriended another French, Marchand (a subordinate of Jacques Law), who later became captain of the French force under Yusuf Khan in Madurai. Whether Yusuf Khan was dismissed from this job or left on his own is unclear. He left Pondicherry, for Tanjore and joined the Tanjorean army as a sepoy (foot soldier).

Around this time, an English captain named Brunton educated Yusuf Khan, making him a learned man well-versed in several languages. From Tanjore he moved to Nellore (in present day Andhra Pradesh), to try his hand as a native physician under Mohammed Kamal, in addition to his career in the army. He moved up the ranks as Thandalgar (tax collector), Havildar and finally as a Subedar and that is how he is referred to in the English records ('Nellore Subedar' or just 'Nellore'). He later enlisted under Chanda Sahib who was then the Nawab of Arcot. While staying in Arcot he fell in love with a 'Portuguese' Christian (a person of mixed Indo-European descent) girl named Maasa (?Marsha /?Marcia), and married her.

In 1751, there was an ongoing scuffle between Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah, (who was the son of the previous Nawab of Arcot Anwaruddin Muhammed Khan hence the rightful claimant) and Chanda Sahib his relative and a pretender, for the throne of Arcot. The former sought the help of British and the latter the French. Chanda Sahib initially succeeded and became the Nawab, forcing Muhammed Ali to escape to the rock-fort in Tiruchirapalli. Chanda Sahib followed and with the help of the French, besieged Trichy. Muhammed Ali and the English force supporting him were in a grim position.

Around this time, an English captain named Brunton educated Yusuf Khan, making him a learned man well-versed in several languages. From Tanjore he moved to Nellore (in present day Andhra Pradesh), to try his hand as a native physician under Mohammed Kamal, in addition to his career in the army. He moved up the ranks as Thandalgar (tax collector), Havildar and finally as a Subedar and that is how he is referred to in the English records ('Nellore Subedar' or just 'Nellore'). He later enlisted under Chanda Sahib who was then the Nawab of Arcot. While staying in Arcot he fell in love with a 'Portuguese' Christian (a person of mixed Indo-European descent) girl named Maasa (?Marsha /?Marcia), and married her.

In 1751, there was an ongoing scuffle between Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah, (who was the son of the previous Nawab of Arcot Anwaruddin Muhammed Khan hence the rightful claimant) and Chanda Sahib his relative and a pretender, for the throne of Arcot. The former sought the help of British and the latter the French. Chanda Sahib initially succeeded and became the Nawab, forcing Muhammed Ali to escape to the rock-fort in Tiruchirapalli. Chanda Sahib followed and with the help of the French, besieged Trichy. Muhammed Ali and the English force supporting him were in a grim position.

Robert Clive, (who had earlier joined the East India Company as a writer) with a small English force of 300 soldiers made a diversionary attack on Arcot to draw away Chanda Sahib's army from Trichy. Chanda Sahib dispatched a 10,000 strong force under his son Raza Sahib to retake Arcot. Raza Sahib was aided by the Nellore Army and Yusuf Khan as a Subedar must have been in this force. At Arcot, and later at Kaveripakkam, Chanda Sahib’s son was badly defeated by Robert Clive, and it was now Chanda Sahib's turn to escape to Tanjore where he was killed by Mankoji, a Tanjorean general. The English quickly installed Muhammed Ali as the Nawab of Arcot and most of Chanda Sahib's native forces defected to the English.

Yusuf Khan's military career started during the Carnatic Wars. Under Major Stringer Lawrence, Yusuf Khan was trained in the European method of warfare and his natural talent in military tactics and strategy blossomed to its full potential.Over the next decade, as the Company fought the French in the Wars of the Carnatic, it was Yusuf Khan's guerrilla tactics, repeatedly cutting the French lines of supply, that did the French in, particularly during Lally's siege of Madras in 1758.Thomas Arthur Lally was to later describe the role of the Nellore Subedar's sepoys in these words: "They were like flies, no sooner beat off from one part, they came from another.

His greatest supporter during this period was George Pigot, the English governor in Madras.

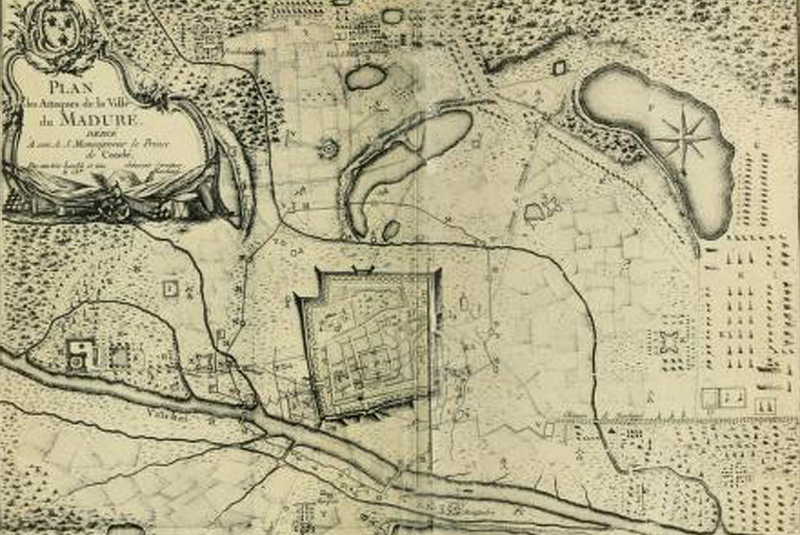

|

| Madurai during Yusuf Khan |

His greatest supporter during this period was George Pigot, the English governor in Madras.

| George Pigot |

Once again Yusuf reached Madurai on May 20, 1759, only to find the place in total chaos. He is believed to have restored order swiftly and was able to remit his rent regularly.

|

| Puli Thevar statue in Nerkattumseval |

Hill in his book points out that apart from remitting his rent regularly, Yusuf Khan managed to create and equip a force with which he could take on the combined forces of the Nawab and the British.

Reports of Yusuf Khan's victories filled the Arcot Nawab with jealousy and alarm that he might depose him. Yusuf Khan instructed all the traders to render taxes directly to him, while the Arcot Nawab wanted to have taxes routed through him. The British Governor Pigot diplomatically advised Yusuf Khan to do as per Arcot Nawab’s order, also some British traders supported the same citing Yusuf Khan as Nawab’s employee. To make matters worse the Nawab’s brother Mahfuz Khan started planning to poison Yusuf Khan, with the whole hearted support of the Nawab.

In 1761, and again in 1762,Yusuf Khan offered to lease Tinnevelly and Madurai for four years more at seven lakhs per annum. His offer was refused, and whether he was enraged at this, or whether he thought himself powerful enough to defy his masters, he shortly afterwards threw off his allegiance and began to collect troops in an ambition to be the lord of Madurai.

| Charles Hill book |

Around this time some British traders reported to the Nawab and the Company, on Yusuf Khan "as encouraging people with anti-British sentiments, spending vast sums on his troops”. Nawab, in turn with the British sent Captain Manson with orders to arrest Yusuf Khan.

Yusuf Khan sent a note to Sivaganga Zamindari reminding them on their pending Tax arrears.Sivaganga’s Minister and General came to meet Yusuf Khan in Madurai, and after not getting their expected respect, got a rude warning, citing annexure of certain territories for the failure of arrears. The enraged Sivaganga Zamindar, immediately ordered Yusuf Khan to be “captured and hanged as like a dog”. Ramnad Zamin’s general Damodar Pillai and Thandavarayan Pillai met the Arcot Nawab in Trichy,complained on Yusuf Khan’s plunderings of Sivaganga villages, his cannon manufacturing plant in association with a certain French Marchaud, whom he a befriended earlier, with plans for a war against the Nawabs.

Arcot Nawab and the British quickly acted by amassing a huge army. For a start they aroused Travancore Raja against Yusuf Khan.In the ensuring battle the Travancore Raja was defeated and the British flags in his domains were chopped and burnt, and joined hands with the French and also hoisted the French flag on the Madurai Fort. When Governor Thomas Saunders in Madras called Khan for a meeting, he refused evoking the wrath of the East India Company.Delhi’s Shah and Nizam Ali of Hyderabad, the Arcot Nawab’s overlords proclaimed Yusuf Khan as the rightful legal governor of Madurai and Tirunelveli regions. Arcot Nawab along with the British was hell bent on finding a reason to capture and kill Yusuf Khan.

Yusuf Khan had enemies lurking around him everywhere. Earlier working for the Arcot Nawab and British he earned the wrath of Mysore, and had slaughtered most of all rebellious Polygars who were anti-British, and the remaining were on the prowl. Now the Tanjore, Travancore, Pudukkotai, Ramnad, Sivaganga kingdoms joined with the British and the Arcot Nawab to attack Yusuf Khan, who by this time had proclaimed himself independent ruler of Madurai and Tirunelveli. In the First siege of Madurai in 1763, the English could not make any headway because of inadequate forces and the army retreated to Tiruchi citing Monsoons.

Nizam Ali of Hyderabad once again proclaimed Yusuf Khan as the Rightful governor, while the Arcot Nawab and the British issued death sentence for Yusuf Khan as “to be captured alive and hanged before the first known tree as like a dog”.

In 1764 again the British troops surrounded the Madurai Fort, this time cutting supplies to the fort.Yusuf Khan and his troops went without food and water for several days inside the fort,surviving on horse and monkey meat according to European sources,but held on with great energy and skill, renovating and strengthening the fort at great expense, and repelling the chief assault with a loss of 120 Europeans including nine officers,killed and wounded. At the end of that time little real progress against him had been made, except that the place was now rigorously blockaded.

The Arcot Nawab consulted Sivaganga General Thaandavaraaya Pillai, along with Major Charles Campbell, hatching a plot to bribe Yusuf khan’s Dewan Srinivasa Rao, Marchand the captain of the French mercenaries and Khan’s doctor Baba Sahib. One morning, when Yusuf Khan was offering his prayers inside the fort, Marchand, Srinivasa Rao and Baba sahib went in quietly and pinned Yusuf Khan to the ground and tied him up using his own turban. Hearing this commotion, one youth called Mudali, close to Yusuf Khan, raised an alarm. He was quickly caught and cut down. As the news of the coup reached Yusuf Khan's wife, she rushed to the scene with a small posse of troops. But they were helpless against the well armed French and other European mercenaries, standing guard around the fallen ruler. Under cover of darkness and an even darker veil of secrecy, Marchand whisked away Yusuf Khan out of the fort and handed him over to Major Charles Campbell, who commanded the English among the besiegers. The major part of Yusuf Khan's native forces remained totally unaware of the fateful drama that had been enacted inside his house.

The next day, in the evening of 15 October 1764, near the army camp at Sammattipuram, on the Madurai- Dindigul road, Yusuf Khan was ignominiously hanged as a rebel by Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah, the Nawab of Arcot. This place is about two miles to the west of Madurai, known as Dabedar Chandai (Shandy), and his body was buried at the spot.

What motives forced the three main conspirators, who were Yusuf Khan's close confidantes, to betray him? It is said that Yusuf Khan had once flogged Marchand with a whip (the first time a European officer had been whipped by a native ruler) and so he was waiting for an opportune time to take revenge. It is also possible that extreme misery of the people and soldiers inside the fort might have forced the Dewan Srinivasa Rao and Baba Sahib, the physician of Yusuf Khan to decide that handing Yusuf Khan over to the English, would make them lift the siege and relieve the people of their intense agony and suffering.

Records show that the British tried to hang yusuf Khan thrice and twice the rope broke.Twice the noose broke down and he fell down alive, for which Yusuf Khan ordered the troops to remove a neck brace before hanging.The agitated Nawab ordered his men to chop his body into several parts and place them all over his domains. As went his head to Tiruchirappalli ,arms to Palayamkottai, legs to Tanjore and Travancore for public viewing and later buried at Periyakulam city near Madurai. The remaining body was buried at Madurai.In 1808, a small square mosque was erected over the tomb in Samattipuram, in Madurai, which exists to this day on the left of the road to Theni, at Kaalavaasal, a little beyond the toll-gate, and is known as 'Khan Sahib's pallivasal'.

Yusuf Khan sent a note to Sivaganga Zamindari reminding them on their pending Tax arrears.Sivaganga’s Minister and General came to meet Yusuf Khan in Madurai, and after not getting their expected respect, got a rude warning, citing annexure of certain territories for the failure of arrears. The enraged Sivaganga Zamindar, immediately ordered Yusuf Khan to be “captured and hanged as like a dog”. Ramnad Zamin’s general Damodar Pillai and Thandavarayan Pillai met the Arcot Nawab in Trichy,complained on Yusuf Khan’s plunderings of Sivaganga villages, his cannon manufacturing plant in association with a certain French Marchaud, whom he a befriended earlier, with plans for a war against the Nawabs.

Arcot Nawab and the British quickly acted by amassing a huge army. For a start they aroused Travancore Raja against Yusuf Khan.In the ensuring battle the Travancore Raja was defeated and the British flags in his domains were chopped and burnt, and joined hands with the French and also hoisted the French flag on the Madurai Fort. When Governor Thomas Saunders in Madras called Khan for a meeting, he refused evoking the wrath of the East India Company.Delhi’s Shah and Nizam Ali of Hyderabad, the Arcot Nawab’s overlords proclaimed Yusuf Khan as the rightful legal governor of Madurai and Tirunelveli regions. Arcot Nawab along with the British was hell bent on finding a reason to capture and kill Yusuf Khan.

Yusuf Khan had enemies lurking around him everywhere. Earlier working for the Arcot Nawab and British he earned the wrath of Mysore, and had slaughtered most of all rebellious Polygars who were anti-British, and the remaining were on the prowl. Now the Tanjore, Travancore, Pudukkotai, Ramnad, Sivaganga kingdoms joined with the British and the Arcot Nawab to attack Yusuf Khan, who by this time had proclaimed himself independent ruler of Madurai and Tirunelveli. In the First siege of Madurai in 1763, the English could not make any headway because of inadequate forces and the army retreated to Tiruchi citing Monsoons.

Nizam Ali of Hyderabad once again proclaimed Yusuf Khan as the Rightful governor, while the Arcot Nawab and the British issued death sentence for Yusuf Khan as “to be captured alive and hanged before the first known tree as like a dog”.

In 1764 again the British troops surrounded the Madurai Fort, this time cutting supplies to the fort.Yusuf Khan and his troops went without food and water for several days inside the fort,surviving on horse and monkey meat according to European sources,but held on with great energy and skill, renovating and strengthening the fort at great expense, and repelling the chief assault with a loss of 120 Europeans including nine officers,killed and wounded. At the end of that time little real progress against him had been made, except that the place was now rigorously blockaded.

The Arcot Nawab consulted Sivaganga General Thaandavaraaya Pillai, along with Major Charles Campbell, hatching a plot to bribe Yusuf khan’s Dewan Srinivasa Rao, Marchand the captain of the French mercenaries and Khan’s doctor Baba Sahib. One morning, when Yusuf Khan was offering his prayers inside the fort, Marchand, Srinivasa Rao and Baba sahib went in quietly and pinned Yusuf Khan to the ground and tied him up using his own turban. Hearing this commotion, one youth called Mudali, close to Yusuf Khan, raised an alarm. He was quickly caught and cut down. As the news of the coup reached Yusuf Khan's wife, she rushed to the scene with a small posse of troops. But they were helpless against the well armed French and other European mercenaries, standing guard around the fallen ruler. Under cover of darkness and an even darker veil of secrecy, Marchand whisked away Yusuf Khan out of the fort and handed him over to Major Charles Campbell, who commanded the English among the besiegers. The major part of Yusuf Khan's native forces remained totally unaware of the fateful drama that had been enacted inside his house.

The next day, in the evening of 15 October 1764, near the army camp at Sammattipuram, on the Madurai- Dindigul road, Yusuf Khan was ignominiously hanged as a rebel by Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah, the Nawab of Arcot. This place is about two miles to the west of Madurai, known as Dabedar Chandai (Shandy), and his body was buried at the spot.

What motives forced the three main conspirators, who were Yusuf Khan's close confidantes, to betray him? It is said that Yusuf Khan had once flogged Marchand with a whip (the first time a European officer had been whipped by a native ruler) and so he was waiting for an opportune time to take revenge. It is also possible that extreme misery of the people and soldiers inside the fort might have forced the Dewan Srinivasa Rao and Baba Sahib, the physician of Yusuf Khan to decide that handing Yusuf Khan over to the English, would make them lift the siege and relieve the people of their intense agony and suffering.

Records show that the British tried to hang yusuf Khan thrice and twice the rope broke.Twice the noose broke down and he fell down alive, for which Yusuf Khan ordered the troops to remove a neck brace before hanging.The agitated Nawab ordered his men to chop his body into several parts and place them all over his domains. As went his head to Tiruchirappalli ,arms to Palayamkottai, legs to Tanjore and Travancore for public viewing and later buried at Periyakulam city near Madurai. The remaining body was buried at Madurai.In 1808, a small square mosque was erected over the tomb in Samattipuram, in Madurai, which exists to this day on the left of the road to Theni, at Kaalavaasal, a little beyond the toll-gate, and is known as 'Khan Sahib's pallivasal'.

Hill's book sums up his life with this quote: “Of Yusuf Khan, there now remains only a little white mosque, a street in Madura known to the people by his name though officially it bears another designation and a fast fading memory of one who, though he died a rebel, had been a gallant and skilful soldier...."

Why Yusuf Khan got converted in the first place? We can only guess based on his other actions and the signs of those times. Between the fall of the Nayak Kingdoms and British take over, Tamil Nadu was total mess, with Arcot, Mysore, Palayakaras, Travancore, French, British, Dutch, Zamindars and all trying to feast on the pieces.

Each bent on betraying the other, making and breaking alliances turns and twists.

Yusuf Khan reminds us of the Condottieri ,mercenary adventurer captains, who switched allegiances by the day. French today, tomorrow Arcot. Day after the British-always looking to make money and aggrandize himself.

For such a person, faith is also matter of convenience. Being a Hindu in those tumultuous times would not have been any advantage and given his colour, Europeans hardly are going to accept him as one of his own.

Condottieri were Italian captains contracted to command mercenary companies during the Middle Ages and multinational armies during the early modern period. They notably served European monarchs and Popes during the Italian Wars of the Renaissance and the European Wars of Religion. Notable condottieri include Prospero Colonna, Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, Cesare Borgia, Andrea Doria, the Duke of Parma, and the Marquis of Pescara.

In 1494, the French king Charles VIII's royal army invaded the Italian peninsula, initiating the Italian Wars. The most renowned condottieri fought for foreign powers: Gian Giacomo Trivulzio abandoned Milan for France, while Andrea Doria was Admiral of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. In the end, failure was political, rather than military, stemming from disunity and political indecision, and, by 1550, the military service condotta had disappeared, while the term condottiere remained current, denominating the great Italian generals (mainly) fighting for foreign states; men such as Gian Giacomo Medici, Ambrogio Spinola, Alexander Farnese, Marcantonio II Colonna, Raimondo Montecuccoli and Prospero Colonna were prominent into the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries. The political practice of hiring foreign mercenaries, however, did not end. For example, the Vatican’s Swiss Guards are the modern remnants of a historically effective mercenary army.

The end of the Thirty Years' War in 1648 and the birth of Westphalian sovereignty diminished Roman Catholic influence in Europe and led to the consolidation of large states, while Italy was fragmented and divided. The condottieri tradition greatly suffered the political and strategic decline of Italy and never recovered.

|

| Portrait of a condottiero by Ermanno Stroiffi |

Yusuf Khan’s loyalties changed by the hour. Finally he grew too large for his boots and the same Nawabs and Colonials who aided his growth, ganged up on him and killed him.

He is not worthy of any honour, just because he was eventually killed by India’s oppressors.

While an adventurer’s story would be an exciting read/movie, Kamal Haasan maybe trying to make him into some kind of an oppressed lower caste hero who rebels against his society, converts and fights against oppression. That is just hijacking an opportunist for his own agendas.

Going to the other conversion,Yusuf Khan had married a christian.

The last great prince of the declining Vijayanagar empire (now in Andhra Pradesh), Venkatapathy Deva Rayalu, conquered the kingdom of Vellore in January 1604 and named it Raya Elluru. Elapuri or Elluru in Telugu language would mean city or town. Raya Elluru was meant a town conquered by the king Rayalu and thus the town was named after him - combination of two words Raya and Elapuri.

There were then some Jesuit Fathers at the court of King Rayalu at Chandragiri. He took them also to his new court at Vellore. The word Vellore derives from the Tamil word ‘Vel’ which means 'spear'; according to another conjecture there were idols of Tamil God ‘Murugan’ holding ‘Vel’ in and around Vellore. Vellore was formerly called Velappadi (a place thickly surrounded by a particular tree called ‘Velamaram’) and for this reason and background the name Vellore came into existence.

Ancient Jesuit documents show that among these Jesuits, there was one named Fr. Antonious Rubunus, a preacher and confessor, who was commuting between Chandragiri and Vellore. He was sent to Japan on 12th August 1642. On 22nd March 1643 he was killed at Nagasaki.

In 1610, there was a general upheaval against the Jesuits,because of persecution.It was due to the dishonourable conduct of the Jesuits that their residences both at Chandragiri and at Vellore were suppressed by a Royal order of the king Philip III of Spain and Portugal in 1611.

© Ramachandran