Prof S K George Lost his Job for Supporting Gandhi

Gandhi was one of those Hindus who had studied the scriptures of all the important religions with open mind and without prejudice. During his prayer meetings, parts of the Bible were read out and at times Psalms were sung along with 'bhajans'. The Sermon on the Mount "went straight to his heart", he used to say. During his life-time Gandhi had developed friendship with several Christians. Some of them had become his followers like C.F. Andrews, Raj Kumari Amrit Kaur; Madeleine Slade (Mirabehn), J.C. Kumarappa,Verrier Elwin,E Stanley Jones and Prof S K George.S K George's serious involvement in the national struggles for Indian Independence dated from his publication in 1932 of his manifesto entitled India in Travail. George was compelled to resign his teaching position in theBishop's College,Calcutta.The French writer and philosopher Romain Rolland who wrote Gandhi's biography,used to call Gandhi a 'second Christ'. In fact Gandhi had shocked the Christian world by living like Jesus without being a Christian.

Gandhi was one of those Hindus who had studied the scriptures of all the important religions with open mind and without prejudice. During his prayer meetings, parts of the Bible were read out and at times Psalms were sung along with 'bhajans'. The Sermon on the Mount "went straight to his heart", he used to say. During his life-time Gandhi had developed friendship with several Christians. Some of them had become his followers like C.F. Andrews, Raj Kumari Amrit Kaur; Madeleine Slade (Mirabehn), J.C. Kumarappa,Verrier Elwin,E Stanley Jones and Prof S K George.S K George's serious involvement in the national struggles for Indian Independence dated from his publication in 1932 of his manifesto entitled India in Travail. George was compelled to resign his teaching position in theBishop's College,Calcutta.The French writer and philosopher Romain Rolland who wrote Gandhi's biography,used to call Gandhi a 'second Christ'. In fact Gandhi had shocked the Christian world by living like Jesus without being a Christian.

One day in 1929, a man went to meet Gandhi at the Sabarmati Ashram. Could he show Gandhi his Ph. D thesis! It contained a different idea of economics. Gandhi read the thesis and was amazed. Here was a man who thought exactly like him. Humans are not merely wealth-producing animals. They were members of society with political, social, moral and spiritual responsibilities. Gandhi immediately asked this man to join him in his efforts to develop a new way of thinking and doing economics.

So Joseph Cornellius Kumarappa, who once was an accountant running his own firm in Mumbai and had just returned from the US, changed his suit for Khadi.

J. C. Kumarappa (born Joseph Chelladurai Cornelius; 1892 - 1960) was an Indian economist and a close associate of Gandhi. A pioneer of rural economic development theories, Kumarappa is credited for developing economic theories based on Gandhism – a school of economic thought he coined "Gandhian economics".

Kumarappa was born in Tanjore, Tamil Nadu, into a Christian family. He was the sixth child of Solomon Doraisamy Cornelius, a Public Works officer, and Esther Rajanayagam. S.D. Cornelius, being one of the great old boys of William Miller, the famous Principal of Madras Christian College, sent his sons JC Cornelius and Benjamin Cornelius to Doveton School and later on to Madras Christian College. After becoming the followers of Gandhi, both the brothers adopted their grand father's name,Kumarappa,and were hailed as Kumarappa brothers. ( The Gandhian Crusader: A Biography of Dr. J.C.Kumarappa, Gandhigram Trust, 1956).Kumarappa later on did economics and chartered accountancy in Britain in 1919. In 1928 he travelled to the United States to obtain degrees in economics and business administration at Syracuse University and Columbia University, studying under Edwin Robert Anderson Seligman.

His older sister, E. S. Appasamy, became a notable educator and social worker in Madras.

On his return to India, Kumarappa published an article on the British tax policy and its exploitation of the Indian economy. He met Gandhi in 1929. At Gandhi's request he prepared an economic survey of rural Gujarat, which he published as A Survey of Matar Taluka in the Kheda District (1931). He strongly supported Gandhi's notion of village industries and promoted Village Industries Associations.

Kumarappa worked to combine Christian and Gandhian values of "trusteeship", non-violence and a focus on human dignity and development in place of materialism as the basis of his economic theories. While rejecting socialism's emphasis on class war and force in implementation, he also rejected the emphasis on material development, competition and efficiency in free-market economics. Gandhi and Kumarappa envisioned an economy focused on satisfying human needs and challenges while rooting out socio-economic conflict, unemployment, poverty and deprivation.

Mirabehn, byname of Madeleine Slade, (1892- 1982) , was a British-born follower of Gandhi who participated in the movement for India’s independence.

Madeleine Slade was the daughter of an English aristocratic family. Because her father, Sir Edmond Slade, was a rear admiral in the British Royal Navy and was often away, Madeleine and her siblings spent much of their childhood at their grandfather’s country home in Surrey. She developed a strong admiration for the music of Ludwig van Beethoven and eventually became a concert manager.

Her aristocratic existence took a life-changing turn after she read French novelist and essayist Romain Rolland’s 1924 biography of Gandhi. In the book the author had described Gandhi as the greatest personality of the 20th century. Slade became fascinated by the principles of nonviolence and contacted Gandhi himself, asking if she could become his disciple and live in his ashram in the western Indian region of Gujarat. Gandhi, while replying in the affirmative, forewarned her of the difficulties of such a life. Undeterred, Slade reached India in November 1925 and made India her home for the next 34 years. She chose not to return to England for personal visits, even when her father died in 1926.

Upon her arrival at the ashram, Gandhi gave her the nickname Mirabehn (“Sister Mira”), named for Mira (or Meera) Bai, the Hindu mystic and great devotee to the god Krishna. She started wearing a white sari, cut her hair short, and took a vow of celibacy. During the first two years in India, she learned Hindi and spent much time spinning and carding cotton. Subsequently, she started travelling to various parts of the country to work in villages.

Mirabehn often accompanied Gandhi on his tours and looked after his personal needs. She became one of Gandhi’s confidants and an ardent champion internationally for India’s freedom from British rule and was with Gandhi at the London Round Table Conference in 1931. In 1934 she made a brief visit to the United States for lectures and radio talks and met first lady Eleanor Roosevelt for an interview at the White House. Before returning to India, she conducted interviews with a number of British politicians in the United Kingdom—Sir Samuel Hoare, Lord Halifax, Winston Churchill, David Lloyd George, and Clement Attlee—as well as the South African leader Jan Smuts.

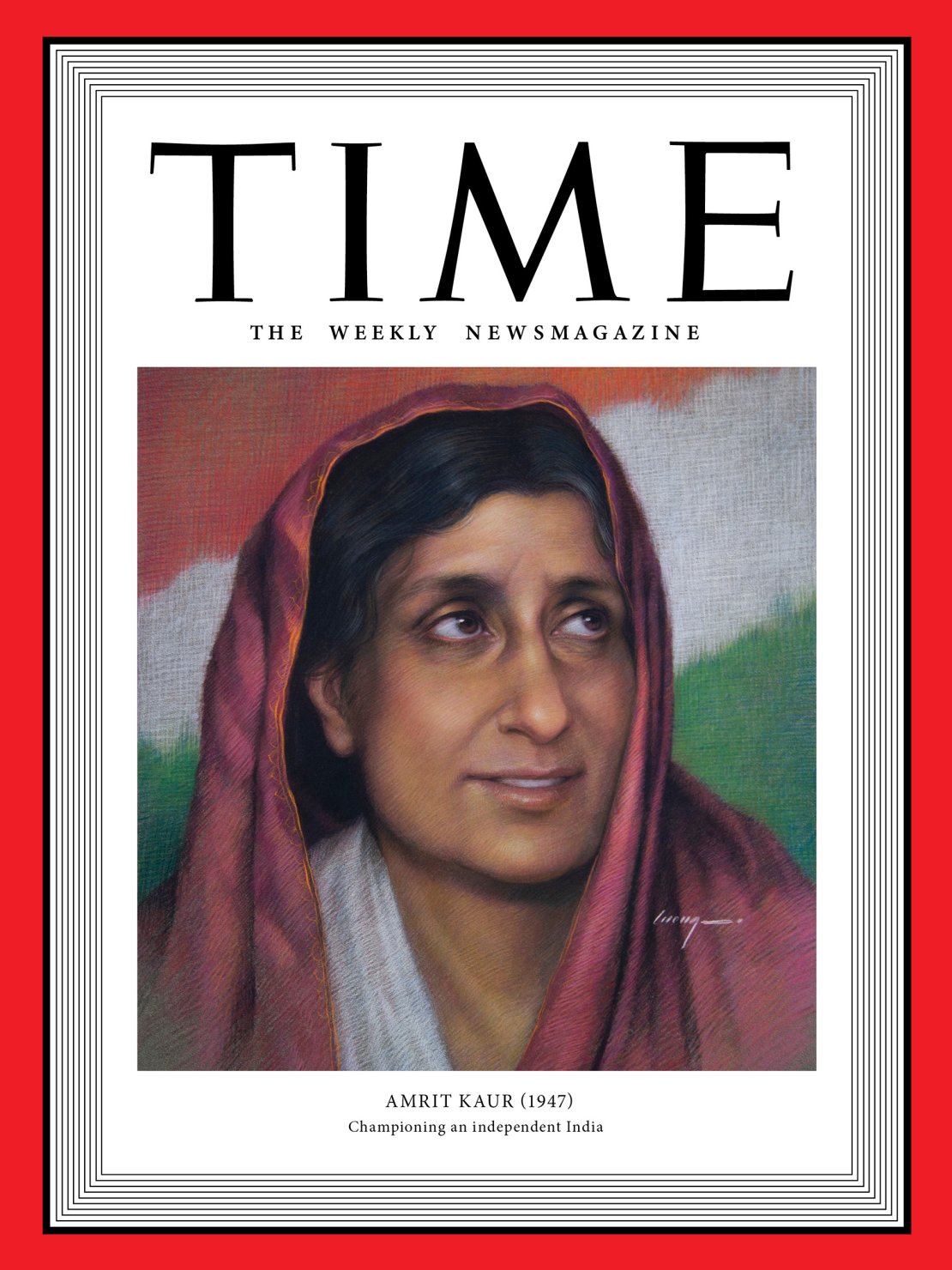

Former prime minister Indira Gandhi and freedom fighter Rajkumari Amrit Kaur were mentioned in TIME magazine’s list of the 100 most powerful women who defined the last century in a new project that aims to feature those women who were “often overshadowed”.

At 20, Kaur returned to India. She was fascinated by the teachings of the Mahatma, and although she would only meet him in 1919, she wrote to him regularly. This would go on to become one of the most enduring epistolary relationships that is documented in Letters to Rajkumari Amrit Kaur. Her parents’ objection to her joining the freedom struggle is what kept Kaur away till 1930, when her father passed away.

Amrit Kaur was the first woman in independent India who joined the Cabinet as the Health Minister and remained in that position for 10 years. Before taking up the position of a Health Minister, Kaur was Mahatma Gandhi’s secretary. During these 10 years, she founded the Indian Council for Child Welfare. She also laid the foundation of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) and Lady Irwin College in Delhi in the following years.

In 1936, hoping that more women would join the freedom struggle, Gandhi wrote to her: “I am now in search of a woman who would realise her mission. Are you that woman, will you be one?”.

In the following years, as Kaur started interacting with other freedom fighters such as Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Gandhi, she gave up her princely comforts and began to discipline herself by responding to the Gandhian call. “The flames of my passionate desire to see India free from foreign domination were fanned by him,” she said. Apart from joining the nationalist freedom struggle, Kaur also began work on a number of other social and political issues such as the purdah system, child marriage and the Devadasi system. When the civil disobedience movement took off in the 1930s, Kaur dedicated her life to it. The independence activist Aruna Asaf Ali wrote about her, “Rajkumari Amrit Kaur belonged to a generation of pioneers. They belonged to well to do homes but gave up on their affluent and sheltered lives and flocked to Gandhiji’s banner when he called women to join the national liberation struggle,”. Kaur was jailed after the Quit India movement and carried to the jail a spinning wheel, the Bhagwat Gita and the Bible.

In time he became an authority on Indian tribal lifestyle and culture, particularly on the Gondi people. He served as the Deputy Director of the Anthropological Survey of India upon its formation in 1945. Post-independence,he took up Indian citizenship.. In January 1954,Elwin became the first foreigner to be accepted as an Indian citizen. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru appointed him as an adviser on tribal affairs for north-eastern India, and later he was Anthropological Adviser to the Government of NEFA (now Arunachal Pradesh. The Government of India awarded him the third highest civilian honour of the Padma Bhushan in 1961. His autobiography, The Tribal World of Verrier Elwin won him the 1965 Sahitya Akademi Award in English Language.

Harry Verrier Holman Elwin was born in Dover.He is the son of Edmund Henry Elwin, Bishop of Sierra Leone. He was educated at Dean Close School and Merton College, Oxford,where he received his degrees of BA First Class in English Language and Literature, MA, and DSc. He also remained the President of Oxford Inter-Collegiate Christian Union (OICCU) in 1925.He had a brilliant career at Oxford, where he took a Double First in English and in Theology, before being ordained a priest in the Church of England. He came to India in 1927, to join a small sect, the Christa Seva Sangh of Poona, which hoped to 'indigenise' Christianity.

The Church has argued that the tribal people are not Hindus, and the missionaries have every right to convert them. However, the research of Verrier Elwin becomes very important, who, after years of meticulous study among the tribal population, concluded: “When I first arrived in aboriginal company thirteen years ago, I was under the impression that the Hillmen were not Hindus. Eight years of hard study and research have convinced me that I was wrong.”

So Joseph Cornellius Kumarappa, who once was an accountant running his own firm in Mumbai and had just returned from the US, changed his suit for Khadi.

J. C. Kumarappa (born Joseph Chelladurai Cornelius; 1892 - 1960) was an Indian economist and a close associate of Gandhi. A pioneer of rural economic development theories, Kumarappa is credited for developing economic theories based on Gandhism – a school of economic thought he coined "Gandhian economics".

|

| Kumarappa |

His older sister, E. S. Appasamy, became a notable educator and social worker in Madras.

On his return to India, Kumarappa published an article on the British tax policy and its exploitation of the Indian economy. He met Gandhi in 1929. At Gandhi's request he prepared an economic survey of rural Gujarat, which he published as A Survey of Matar Taluka in the Kheda District (1931). He strongly supported Gandhi's notion of village industries and promoted Village Industries Associations.

Kumarappa worked to combine Christian and Gandhian values of "trusteeship", non-violence and a focus on human dignity and development in place of materialism as the basis of his economic theories. While rejecting socialism's emphasis on class war and force in implementation, he also rejected the emphasis on material development, competition and efficiency in free-market economics. Gandhi and Kumarappa envisioned an economy focused on satisfying human needs and challenges while rooting out socio-economic conflict, unemployment, poverty and deprivation.

He was described one of the "Christians of the inner Gandhi circle" – which included non-Indians such as C F Andrews, Verrier Elwin and R. R. Keithahn, and Indians such as Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, S. K. George, Aryanayagam and B. Kumarappa, all of whom espoused the philosophy of non-violence. J. C. Kumarappa responded positively to the Indian national renaissance, and he and George rejected the idea that British rule in India was ordained by divine providence.

Kumarappa worked as a professor of economics at the Gujarat Vidyapith in Ahmedabad, while serving as the editor of Young India during the Salt Satyagraha, between May 1930 and February 1931. He helped found and organise the All India Village Industries Association in 1935; and was imprisoned for more than a year during the Quit India movement. He wrote during his imprisonment, Economy of Permanence, The Practice and Precepts of Jesus (1945) and Christianity: Its Economy and Way of Life (1945).

Several of Gandhi's followers developed a theory of environmentalism. Kumarappa took the lead in a number of relevant books in the 1930s and 1940s. He and Mirabehn argued against large-scale dam-and-irrigation projects, saying that small projects were more efficacious, that organic manure was better and less dangerous than man-made chemicals, and that forests should be managed with the goal of water conservation rather than revenue maximisation. The British and the Nehru governments paid them little attention. Historian Ramachandra Guha calls Kumarappa, "The Green Gandhian," portraying him as the founder of modern environmentalism in India.

After India's independence in 1947, Kumarappa worked for the Planning Commission of India and the Indian National Congress to develop national policies for agriculture and rural development. He also travelled to China, eastern Europe and Japan on diplomatic assignments and to study their rural economic systems. He spent some time in Sri Lanka, where he received Ayurvedic treatment. He settled near Madurai at the Gandhi Niketan Ashram, T.Kallupatti (a school based on Gandhian education system) constructed by freedom fighter and Gandhian follower K. Venkatachalapathi, where he continued his work in economics and writing.

He died on 30 January 1960. The Kumarappa Institute of Gram Swaraj was founded in his honour. His younger brother Bharatan Kumarappa was also associated with Gandhi and the Sarvodaya movement.

Charles Freer Andrews ( 1871 – 1940) was a priest of the Church of England. A Christian missionary, educator and social reformer in India, he became a close friend of Rabindranath Tagore and Gandhi and identified with the cause of India's independence. He was instrumental in convincing Gandhi to return to India from South Africa.

C. F. Andrews was affectionately dubbed Christ's Faithful Apostle by Gandhi, based on his initials, C.F.A. For his contributions to the Indian Independence Movement Gandhi and his students at St. Stephen's College, Delhi, named him Deenabandhu, or "Friend of the Poor".

Andrews was born on 12 February 1871 at 14 Brunel Terrace, Newcastle upon Tyne, Northumberland, United Kingdom; his father was the "Angel" (bishop) of the Catholic Apostolic Church in Birmingham. The family had suffered financial misfortune because of the duplicity of a friend, and had to work hard to make ends meet. Andrews was a pupil at King Edward's School, Birmingham, and afterwards read Classics at Pembroke College, Cambridge. During this period he moved away from his family's church and was accepted for ordination in the Church of England.

In 1896 Andrews became a deacon, and took over the Pembroke College Mission in south London. A year later he was made priest, and became Vice-Principal of Westcott House Theological College in Cambridge.

He was involved in the Christian Social Union since university, and was interested in exploring the relationship between a commitment to the Gospel and a commitment to justice, through which he was attracted to struggles for justice throughout the British Empire, especially in India.

In 1904 he joined the Cambridge Mission to Delhi and arrived there to teach philosophy at St. Stephen's College, where he grew close to many of his Indian colleagues and students. Increasingly dismayed by the racist behaviour and treatment of Indians by some British officials and civilians, he supported Indian political aspirations, and wrote a letter in the Civil and Military Gazette in 1906 voicing these sentiments. Andrews soon became involved in the activities of the Indian National Congress, and he helped to resolve the 1913 cotton workers' strike in Madras.

Known for his persuasiveness, intellect and moral rectitude, he was asked by senior Indian political leader Gopal Krishna Gokhale to visit South Africa and help the Indian community there to resolve their political disputes with the Government. Arriving in January 1914, he met the 44-year-old Gujarati lawyer, Mohandas Gandhi, who was leading the Indian community's efforts against the racial discrimination and police legislation that infringed their civil liberties. Andrews was deeply impressed with Gandhi's knowledge of Christian values and his espousal of the concept of ahimsa (nonviolence).

Andrews served as Gandhi's aide in his negotiations with General Jan Smuts and was responsible for finalizing some of the finer details of their interactions.

Following the advice of several Indian Congress leaders and of Principal Susil Kumar Rudra, of St. Stephen's College, Andrews was instrumental in persuading Gandhi to return to India with him in 1915.

In 1918 Andrews disagreed with Gandhi's attempts to recruit combatants for World War I, believing that this was inconsistent with their views on nonviolence. In Mahatma Gandhi's Ideas, Andrews wrote about Gandhi's recruitment campaign: "Personally I have never been able to reconcile this with his own conduct in other respects, and it is one of the points where I have found myself in painful disagreement."

Andrews was elected President of the All India Trade Union in 1925 and 1927.

Andrews developed a dialogue between Christians and Hindus. He spent a lot of time at Santiniketan in conversation with Tagore. He also supported the movement to ban the ‘untouchability of outcasts’. He joined the famous Vaikom Satyagraha, and in 1933 assisted B.R. Ambedkar in formulating the demands of the Dalits.

Andrews, along with Tagore, visited Sree Narayana Guru, spiritual leader from Kerala, South India. Then he wrote to Romain Rolland:" I have seen our Christ walking on the shore of Arabian sea in the attire of a hindu sanyasin".

Kumarappa worked as a professor of economics at the Gujarat Vidyapith in Ahmedabad, while serving as the editor of Young India during the Salt Satyagraha, between May 1930 and February 1931. He helped found and organise the All India Village Industries Association in 1935; and was imprisoned for more than a year during the Quit India movement. He wrote during his imprisonment, Economy of Permanence, The Practice and Precepts of Jesus (1945) and Christianity: Its Economy and Way of Life (1945).

Several of Gandhi's followers developed a theory of environmentalism. Kumarappa took the lead in a number of relevant books in the 1930s and 1940s. He and Mirabehn argued against large-scale dam-and-irrigation projects, saying that small projects were more efficacious, that organic manure was better and less dangerous than man-made chemicals, and that forests should be managed with the goal of water conservation rather than revenue maximisation. The British and the Nehru governments paid them little attention. Historian Ramachandra Guha calls Kumarappa, "The Green Gandhian," portraying him as the founder of modern environmentalism in India.

After India's independence in 1947, Kumarappa worked for the Planning Commission of India and the Indian National Congress to develop national policies for agriculture and rural development. He also travelled to China, eastern Europe and Japan on diplomatic assignments and to study their rural economic systems. He spent some time in Sri Lanka, where he received Ayurvedic treatment. He settled near Madurai at the Gandhi Niketan Ashram, T.Kallupatti (a school based on Gandhian education system) constructed by freedom fighter and Gandhian follower K. Venkatachalapathi, where he continued his work in economics and writing.

He died on 30 January 1960. The Kumarappa Institute of Gram Swaraj was founded in his honour. His younger brother Bharatan Kumarappa was also associated with Gandhi and the Sarvodaya movement.

Charles Freer Andrews ( 1871 – 1940) was a priest of the Church of England. A Christian missionary, educator and social reformer in India, he became a close friend of Rabindranath Tagore and Gandhi and identified with the cause of India's independence. He was instrumental in convincing Gandhi to return to India from South Africa.

C. F. Andrews was affectionately dubbed Christ's Faithful Apostle by Gandhi, based on his initials, C.F.A. For his contributions to the Indian Independence Movement Gandhi and his students at St. Stephen's College, Delhi, named him Deenabandhu, or "Friend of the Poor".

Andrews was born on 12 February 1871 at 14 Brunel Terrace, Newcastle upon Tyne, Northumberland, United Kingdom; his father was the "Angel" (bishop) of the Catholic Apostolic Church in Birmingham. The family had suffered financial misfortune because of the duplicity of a friend, and had to work hard to make ends meet. Andrews was a pupil at King Edward's School, Birmingham, and afterwards read Classics at Pembroke College, Cambridge. During this period he moved away from his family's church and was accepted for ordination in the Church of England.

In 1896 Andrews became a deacon, and took over the Pembroke College Mission in south London. A year later he was made priest, and became Vice-Principal of Westcott House Theological College in Cambridge.

He was involved in the Christian Social Union since university, and was interested in exploring the relationship between a commitment to the Gospel and a commitment to justice, through which he was attracted to struggles for justice throughout the British Empire, especially in India.

In 1904 he joined the Cambridge Mission to Delhi and arrived there to teach philosophy at St. Stephen's College, where he grew close to many of his Indian colleagues and students. Increasingly dismayed by the racist behaviour and treatment of Indians by some British officials and civilians, he supported Indian political aspirations, and wrote a letter in the Civil and Military Gazette in 1906 voicing these sentiments. Andrews soon became involved in the activities of the Indian National Congress, and he helped to resolve the 1913 cotton workers' strike in Madras.

Known for his persuasiveness, intellect and moral rectitude, he was asked by senior Indian political leader Gopal Krishna Gokhale to visit South Africa and help the Indian community there to resolve their political disputes with the Government. Arriving in January 1914, he met the 44-year-old Gujarati lawyer, Mohandas Gandhi, who was leading the Indian community's efforts against the racial discrimination and police legislation that infringed their civil liberties. Andrews was deeply impressed with Gandhi's knowledge of Christian values and his espousal of the concept of ahimsa (nonviolence).

Andrews served as Gandhi's aide in his negotiations with General Jan Smuts and was responsible for finalizing some of the finer details of their interactions.

Following the advice of several Indian Congress leaders and of Principal Susil Kumar Rudra, of St. Stephen's College, Andrews was instrumental in persuading Gandhi to return to India with him in 1915.

In 1918 Andrews disagreed with Gandhi's attempts to recruit combatants for World War I, believing that this was inconsistent with their views on nonviolence. In Mahatma Gandhi's Ideas, Andrews wrote about Gandhi's recruitment campaign: "Personally I have never been able to reconcile this with his own conduct in other respects, and it is one of the points where I have found myself in painful disagreement."

Andrews was elected President of the All India Trade Union in 1925 and 1927.

Andrews developed a dialogue between Christians and Hindus. He spent a lot of time at Santiniketan in conversation with Tagore. He also supported the movement to ban the ‘untouchability of outcasts’. He joined the famous Vaikom Satyagraha, and in 1933 assisted B.R. Ambedkar in formulating the demands of the Dalits.

Andrews, along with Tagore, visited Sree Narayana Guru, spiritual leader from Kerala, South India. Then he wrote to Romain Rolland:" I have seen our Christ walking on the shore of Arabian sea in the attire of a hindu sanyasin".

|

| Andrews ( far left) with Gandhi |

He and Agatha Harrison arranged for Gandhi's visit to the UK. He accompanied Gandhi to the second Round Table Conference in London, helping him to negotiate with the British government on matters of Indian autonomy and devolution.

When the news reached India, of the mistreatment of Indian indentured labourers in Fiji, the Indian Government in September 1915 sent Andrews and William W. Pearson to make inquiries. The two visited numerous plantations and interviewed indentured labourers, overseers and Government officials and on their return to India also interviewed returned labourers. In their "Report on Indentured Labour in Fiji" Andrews and Pearson highlighted the ills of the indenture system; which led to the end of further transportation of Indian labour to the British colonies. In 1917 Andrews made a second visit to Fiji, and although he reported some improvements, was still appalled at the moral degradation of indentured labourers. He called for an immediate end to indenture; and the system of Indian indentured labour was formally abolished in 1920.

In 1936, while on a visit to Australia and New Zealand, Andrews was invited to and visited Fiji again. The ex-indentured labourers and their descendants wanted him to help them overcome a new type of slavery, by which they were bound to the Colonial Sugar Refining Company, which controlled all aspects of their lives. Andrews, however, was delighted with the improvements in conditions since his last visit, and asked Fiji Indians to "remember that Fiji belonged to the Fijians and they were there as guests.

About this time Gandhi reasoned with Andrews that it was probably best for sympathetic Britons like himself to leave the freedom struggle to Indians. So from 1935 onwards Andrews began to spend more time in Britain, teaching young people all over the country about Christ's call to radical discipleship. He was widely known as Gandhi's closest friend and was perhaps the only major figure to address Gandhi by his first name, Mohan.

He died on 5 April 1940, during a visit to Calcutta, and is buried in the 'Christian Burial ground' of Lower Circular Road cemetery, Calcutta.

When the news reached India, of the mistreatment of Indian indentured labourers in Fiji, the Indian Government in September 1915 sent Andrews and William W. Pearson to make inquiries. The two visited numerous plantations and interviewed indentured labourers, overseers and Government officials and on their return to India also interviewed returned labourers. In their "Report on Indentured Labour in Fiji" Andrews and Pearson highlighted the ills of the indenture system; which led to the end of further transportation of Indian labour to the British colonies. In 1917 Andrews made a second visit to Fiji, and although he reported some improvements, was still appalled at the moral degradation of indentured labourers. He called for an immediate end to indenture; and the system of Indian indentured labour was formally abolished in 1920.

In 1936, while on a visit to Australia and New Zealand, Andrews was invited to and visited Fiji again. The ex-indentured labourers and their descendants wanted him to help them overcome a new type of slavery, by which they were bound to the Colonial Sugar Refining Company, which controlled all aspects of their lives. Andrews, however, was delighted with the improvements in conditions since his last visit, and asked Fiji Indians to "remember that Fiji belonged to the Fijians and they were there as guests.

About this time Gandhi reasoned with Andrews that it was probably best for sympathetic Britons like himself to leave the freedom struggle to Indians. So from 1935 onwards Andrews began to spend more time in Britain, teaching young people all over the country about Christ's call to radical discipleship. He was widely known as Gandhi's closest friend and was perhaps the only major figure to address Gandhi by his first name, Mohan.

He died on 5 April 1940, during a visit to Calcutta, and is buried in the 'Christian Burial ground' of Lower Circular Road cemetery, Calcutta.

| Mirabehn |

Madeleine Slade was the daughter of an English aristocratic family. Because her father, Sir Edmond Slade, was a rear admiral in the British Royal Navy and was often away, Madeleine and her siblings spent much of their childhood at their grandfather’s country home in Surrey. She developed a strong admiration for the music of Ludwig van Beethoven and eventually became a concert manager.

Her aristocratic existence took a life-changing turn after she read French novelist and essayist Romain Rolland’s 1924 biography of Gandhi. In the book the author had described Gandhi as the greatest personality of the 20th century. Slade became fascinated by the principles of nonviolence and contacted Gandhi himself, asking if she could become his disciple and live in his ashram in the western Indian region of Gujarat. Gandhi, while replying in the affirmative, forewarned her of the difficulties of such a life. Undeterred, Slade reached India in November 1925 and made India her home for the next 34 years. She chose not to return to England for personal visits, even when her father died in 1926.

Upon her arrival at the ashram, Gandhi gave her the nickname Mirabehn (“Sister Mira”), named for Mira (or Meera) Bai, the Hindu mystic and great devotee to the god Krishna. She started wearing a white sari, cut her hair short, and took a vow of celibacy. During the first two years in India, she learned Hindi and spent much time spinning and carding cotton. Subsequently, she started travelling to various parts of the country to work in villages.

Mirabehn often accompanied Gandhi on his tours and looked after his personal needs. She became one of Gandhi’s confidants and an ardent champion internationally for India’s freedom from British rule and was with Gandhi at the London Round Table Conference in 1931. In 1934 she made a brief visit to the United States for lectures and radio talks and met first lady Eleanor Roosevelt for an interview at the White House. Before returning to India, she conducted interviews with a number of British politicians in the United Kingdom—Sir Samuel Hoare, Lord Halifax, Winston Churchill, David Lloyd George, and Clement Attlee—as well as the South African leader Jan Smuts.

| Mirabehn with Secretary Brahmachari Dutt |

Mirabehn was active in spreading the spirit of nonviolence, and she was considered by the British to be important to India’s independence movement. She was arrested multiple times, including during a period of civil disobedience in 1932–33, when she was detained on the charge of supplying information to Europe and America regarding conditions prevailing in India; and in 1942, when she was imprisoned in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune along with Gandhi and his wife, Kasturba.

In 1946 Mirabehn was appointed as honorary special adviser to the Uttar Pradesh government to assist in a campaign to expand agricultural production. In 1947 she set up an ashram near Rishikesh. Following Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, Mirabehn decided to stay in India. For the next 11 years, she travelled to various Indian states, took on community projects including one that came to be known as the Gopal Ashram in the Bhilangana valley and worked on environmental issues such as those preventing deforestation and implementing flood-control measures. She even experimented with the introduction of Dexter cattle from England for crossbreeding with the yak in Jammu and Kashmir.

Mirabehn returned to England in 1959 and a year later moved to a house near Vienna, where she spent the remaining years of her life. A year before her death, the Indian government conferred on her the Padma Vibhushan medal, the country’s second highest civilian honour.

Among her writings are New and Old Gleanings, published in 1960 (an updated edition of Gleanings Gathered at Bapu’s Feet, originally published in 1949), and her autobiography, The Spirit’s Pilgrimage,( 1960).Sudhir Kakar's novel,Mira and Mahatma,portrays the special relationship between nthe two,hinting at a jealousy on the part of Kasthurba.

In 1946 Mirabehn was appointed as honorary special adviser to the Uttar Pradesh government to assist in a campaign to expand agricultural production. In 1947 she set up an ashram near Rishikesh. Following Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, Mirabehn decided to stay in India. For the next 11 years, she travelled to various Indian states, took on community projects including one that came to be known as the Gopal Ashram in the Bhilangana valley and worked on environmental issues such as those preventing deforestation and implementing flood-control measures. She even experimented with the introduction of Dexter cattle from England for crossbreeding with the yak in Jammu and Kashmir.

Mirabehn returned to England in 1959 and a year later moved to a house near Vienna, where she spent the remaining years of her life. A year before her death, the Indian government conferred on her the Padma Vibhushan medal, the country’s second highest civilian honour.

Among her writings are New and Old Gleanings, published in 1960 (an updated edition of Gleanings Gathered at Bapu’s Feet, originally published in 1949), and her autobiography, The Spirit’s Pilgrimage,( 1960).Sudhir Kakar's novel,Mira and Mahatma,portrays the special relationship between nthe two,hinting at a jealousy on the part of Kasthurba.

|

Born on 2 February, 1889, to the royal family of Kapurthala, Amrit Kaur grew up in a Christian household as her father converted to Christianity before she was born, and her mother was a Bengali Christian.Kaur spent her early years in Kapurthala, Punjab, and then moved to Sherborne School in Dorset, UK. She excelled at the school, was the “head girl” and the captain of the cricket, hockey and lacrosse team. She spent her undergraduate years at Oxford.She returned to India in 1918, and began to be drawn towards the work and teachings of Gandhi.

Amrit Kaur was the first woman in independent India who joined the Cabinet as the Health Minister and remained in that position for 10 years. Before taking up the position of a Health Minister, Kaur was Mahatma Gandhi’s secretary. During these 10 years, she founded the Indian Council for Child Welfare. She also laid the foundation of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) and Lady Irwin College in Delhi in the following years.

In 1936, hoping that more women would join the freedom struggle, Gandhi wrote to her: “I am now in search of a woman who would realise her mission. Are you that woman, will you be one?”.

In the following years, as Kaur started interacting with other freedom fighters such as Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Gandhi, she gave up her princely comforts and began to discipline herself by responding to the Gandhian call. “The flames of my passionate desire to see India free from foreign domination were fanned by him,” she said. Apart from joining the nationalist freedom struggle, Kaur also began work on a number of other social and political issues such as the purdah system, child marriage and the Devadasi system. When the civil disobedience movement took off in the 1930s, Kaur dedicated her life to it. The independence activist Aruna Asaf Ali wrote about her, “Rajkumari Amrit Kaur belonged to a generation of pioneers. They belonged to well to do homes but gave up on their affluent and sheltered lives and flocked to Gandhiji’s banner when he called women to join the national liberation struggle,”. Kaur was jailed after the Quit India movement and carried to the jail a spinning wheel, the Bhagwat Gita and the Bible.

Gandhi would affectionately use the epithet ‘idiot’ or ‘rebel’ for Kaur, and would sign his letters as ‘robber’ and ‘tyrant’, respectively. They developed such a lasting friendship that they continued to write to each even during their jail terms after the Quit India Movement.

Further, while Kaur advocated for equality, she was not in favour of reservations for women and believed that universal adult franchise would open the doors for women to enter into the legislative and administrative institutions of the country. In light of this, she believed that there was no place left for reservation of seats.

She passed away in 1964, at the age of 75. While she was a practicing Roman Catholic, she was cremated as per Sikh rituals in the Yamuna.

Further, while Kaur advocated for equality, she was not in favour of reservations for women and believed that universal adult franchise would open the doors for women to enter into the legislative and administrative institutions of the country. In light of this, she believed that there was no place left for reservation of seats.

She passed away in 1964, at the age of 75. While she was a practicing Roman Catholic, she was cremated as per Sikh rituals in the Yamuna.

|

| Verrier Elwin |

Verrier Elwin (1902- 1964 ) was a British-born anthropologist, ethnologist and tribal activist, who began his career in India as a Christian missionary. He first abandoned the clergy, to work with Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, then converted to Hinduism in 1935 after staying in a Gandhian ashram and split with the nationalists over what he felt was an overhasty process of transformation and assimilation for the tribals. Verrier Elwin is best known for his early work with the Baigas and Gonds of Orissa and Madhya Pradesh in central India, and he married a member of one of the communities he studied. He later also worked on the tribals of several North East Indian states especially North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) and settled in Shillong, the hill capital of Meghalaya.

In time he became an authority on Indian tribal lifestyle and culture, particularly on the Gondi people. He served as the Deputy Director of the Anthropological Survey of India upon its formation in 1945. Post-independence,he took up Indian citizenship.. In January 1954,Elwin became the first foreigner to be accepted as an Indian citizen. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru appointed him as an adviser on tribal affairs for north-eastern India, and later he was Anthropological Adviser to the Government of NEFA (now Arunachal Pradesh. The Government of India awarded him the third highest civilian honour of the Padma Bhushan in 1961. His autobiography, The Tribal World of Verrier Elwin won him the 1965 Sahitya Akademi Award in English Language.

Elwin married a 13 year old Raj Gond tribal girl called Kosi who was a student at his school at Raythwar (Raithwar) in Dindori district in Madhya Pradesh on 4 April 1940. They had one son, Jawaharlal (Kumar), born in 1941. Elwin had an ex-parte divorce in 1949, at the Calcutta High Court, writing in his autobiography, "I cannot even now look back on this period of my life without a deep sense of pain and failure". In 2006 Kosi was still living in a hut in Raythwar, their son Kumar having died. The couple's second son, Vijay, also died young. Elwin remarried a woman called Lila, belonging to the Pardhan Gond tribe in nearby Patangarh, moving with her to Shillong in the early 1950s. They had three sons, Wasant, Nakul and Ashok. Elwin died in Delhi on 22 February 1964 after a heart attack. His widow Lila died in Mumbai in 2013, aged about 80, shortly after the demise of their eldest son, Wasant. His marriage to Lila connected Verrier to Jangarh Singh Shyam, the Gond artist.

The first meeting between Stanley Jones and Gandhi took place

in 1919 when Jones was at St. Stephen's College, Delhi to address the

students. Susil Rudra, the Principal, introduced him to Gandhi. It was

followed by a conversation about how Christianity could be naturalised

in India86. Jones was impressed by Gandhi’s faithfulness to the moral

ideal of Christ and remarked: Gandhi went by manifesting a Christian

spirit far beyond most of the Christians.

Jones’s next meeting with Gandhi was in Poona in 1924. That

was when Gandhi was temporarily released from the jail for an operation. Jones asked for a message he could take back with him to

the west as to how we should live this Christian life? Gandhi replied:

“Such a message cannot be given by word of mouth; it can only be

lived”88. Though this reply impressed Jones, the evangelist in Jones

persuaded Gandhi that he ought to make Christ the centre of his nonviolent movement for it could then readily appreciated by the west. “If

you will give a clear-cut witness to Jesus, then a world kingdom is

awaiting you”89. Also Jones wanted Gandhi to declare a personal

allegiance to Christ, though he added that he did not mean coming out

and being a baptised Christian. He left that for Gandhi to decide. But to

the disappointment of Jones, Gandhi did neither.

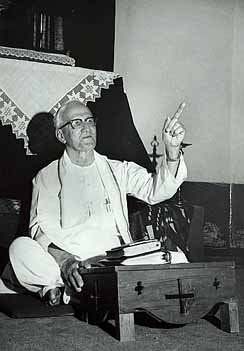

|

| Stanley Jones |

Jones admiration of Gandhi was not uncritical. He viewed

every word and every deed of Gandhi from a strictly Christianevangelical point of view and critiqued them. Jones was provoked by

Gandhi’s speech in the missionaries’ meet in Calcutta YWCA where

he said: “Hinduism, as I know, entirely satisfies my soul, fills my

whole being, and I find solace in the Bhagavadgita and the

Upanishads that I miss even in the Sermon on the Mount”90. In the

above words Jones sensed a serious weakness in Gandhi’s

understanding of Christ and was disappointed about it He wrote:

“I think you have grasped certain principles of the Christian

faith which have moulded you and have helped make you greatyou have grasped the principles, but you have missed the

person. You said in Calcutta to the missionaries that you did not

turn to the Sermon on the Mount for consolation, but to the

Bhagavadgita. Nor do I turn to the Sermon on the Mount for

consolation, but to this person who embodies and illustrates the

Sermon on the Mount, but he is much more. Here is where I

think you are weakest in your grasp. May I suggest that you

penetrate through the principles to the person and then come

back and tell us what you have found. I don’t say this as a mere

Christian propagandist. I say this because we need you and need

the illustration you could give us if you really grasp the centre

the person”.

The point raised by Jones regarding the precedence to be

accorded to the person of Jesus was not new to Gandhi. But he stuck to

his position that Jesus was one among the great teachers of the world

and his life inspired him as an embodiment of sacrifice.

C. F. Andrews, S. K. George and Stanley Jones who were

Gandhi’s close Christian friends were in full agreement that Gandhi

had manifested in his life a true Christliness. They said that they

themselves and the Christian world as a whole were enriched by

Gandhi’s practical application of the Christian principles. They

emphasised that living like Christ-in other words imitation of Christwas more important than preaching or teaching of any Christian

dogmas or traditions. Coming under Gandhi’s influence they modified

their traditional views and challenged Christians to give more

importance to practical aspects of religion rather than mere dogmas or

creed. They firmly believed that Gandhi posed an un-mistakable

challenge before the Christian world as he was more Christianised than

many who claimed to be Christians and his precepts were really valid

for Christianity for its healthy conduct in a pluralistic context.

S K George,a Keralite from Thrissur in Gandhi's fold,wrote,Gandhi's Challenge to Christianity,which made the anti Gandhi Church,furious.

S K George,who lived in Sabarmathi and Santiniketan after resigning as lecturer in Bishop's College,Calcutta in 1932,published the book in London in 1939 with a foreword by S Radhakrishnan;its second edition was published in 1947 by Navjivan Trust with an added preface by Horace Alexander.

When the young theologian stepped out of the portals of the Bishop’s College Calcutta in 1932, little did he realize that the teachings of Christ would be religiously followed by an ‘unbeliever’. Much to the shock of his relatives and friends w ho expected him to be conventional parson of the Anglican Church,Srampickal Kuruvilla George by the message and teachings of Gandhi.

For George,the practice of redemptive suffering love manifested in the cross of Christ was the central principle of Christianity.Gandhi's satyagraha movement was for him the cross in action and he joined it wholeheartedly in 1932,resigning his job.Even prior to this,as a Bachelor of Divinity student of Bishop's College ( 1924-27),he had his doubts about the exclusive divinity of Christ.As early as George helped in organizing the All Kerala Inter-Religious Students Fellowship,which tried to bring together students of various of various religions for mutual understanding and co-operation.The first conference of the Fellowship was held at Alwaye in May 1937.

George saw in Gandhi, a person who dared to live the Christian life and even called others to do so.Never had he seen anyone who treated the Gita and the Sermon on the Mount as Gospels. His conviction to follow the Gandhian way also gave him enough audacity to express theological doubts pertaining to the exclusive Divinity of Christ. Theologians, who were taken by surprise at George’s affirmations,postponed his ordination as a priest of the Church, hoping that he would come back to the real faith of the Church.

Since the irrevocable had happened, George became a social leper in theological circles. Unmindful of the hostility, George went a step further. In the 1930s, when the Church in India did not show any sympathy towards the national movement, George urged the Christians to join the Civil Disobedience Movement for he firmly believed that the ‘satyagraha’ ‘was the Cross in action’. He published an appeal to all Indian Christians and the Church to join in and act as custodians of non-violence as a community which claimed to believe in the supreme instance of the triumphant satyagraha the world has seen, viz, the Cross of Jesus of Nazareth. The Bengal Government took objection to this statement and two Calcutta papers were penalized. George himself escaped Government prosecution. But this sympathy with Indian nationalism was regarded as disloyalty to the Church and the Government.

The then head of the Anglican Church in India, Metropolitan Foss Westcott, had condemned the Disobedience Movement as unchristian and even justified the British law comparing it to the law of Nature. However, George confronted his stand by drawing a parallel between the revolt of Israelites mentioned in the Bible to the Disobedience Movement what followed was a theological battle.

George said: " One striking biblical parallel suggests itself to me whenever I think of Gandhiji, namelythat of Moses leading the revolt of the Israelites, creating disaffection among them against constituted authority and leading them to independence. Moses would stand condemned by your Lordship’s argument from the analogy of the laws of Nature."

George saw in Gandhi, a person who dared to live the Christian life and even called others to do so.Never had he seen anyone who treated the Gita and the Sermon on the Mount as Gospels. His conviction to follow the Gandhian way also gave him enough audacity to express theological doubts pertaining to the exclusive Divinity of Christ. Theologians, who were taken by surprise at George’s affirmations,postponed his ordination as a priest of the Church, hoping that he would come back to the real faith of the Church.

Since the irrevocable had happened, George became a social leper in theological circles. Unmindful of the hostility, George went a step further. In the 1930s, when the Church in India did not show any sympathy towards the national movement, George urged the Christians to join the Civil Disobedience Movement for he firmly believed that the ‘satyagraha’ ‘was the Cross in action’. He published an appeal to all Indian Christians and the Church to join in and act as custodians of non-violence as a community which claimed to believe in the supreme instance of the triumphant satyagraha the world has seen, viz, the Cross of Jesus of Nazareth. The Bengal Government took objection to this statement and two Calcutta papers were penalized. George himself escaped Government prosecution. But this sympathy with Indian nationalism was regarded as disloyalty to the Church and the Government.

The then head of the Anglican Church in India, Metropolitan Foss Westcott, had condemned the Disobedience Movement as unchristian and even justified the British law comparing it to the law of Nature. However, George confronted his stand by drawing a parallel between the revolt of Israelites mentioned in the Bible to the Disobedience Movement what followed was a theological battle.

George said: " One striking biblical parallel suggests itself to me whenever I think of Gandhiji, namelythat of Moses leading the revolt of the Israelites, creating disaffection among them against constituted authority and leading them to independence. Moses would stand condemned by your Lordship’s argument from the analogy of the laws of Nature."

In his reply the Metropolitan stated: I always understood that Moses went with the full permission of Pharaoh… but his pursuit was arrested not by the violence of Moses but by what is recorded as an act of God". And in his reply to this, George said: "You say our Lord kept out of politics, but we are not to bring Him into our politics if He is to be the Lord of all life?… And I challenge anyone to say that in principle the war of non-violent disobedience to an unjust law is against the teaching of Christ."

|

In the preface to his book on Gandhi,,George wrote:

"I do not claim to be great anything; but I

do claim to be a Gandhiite and a Christian. That combination is to me vital and

significant for the world today and especially so for India. The conviction came

to me as a young man in the beginnings of the Gandhian era in Indian politics, a

conviction that has only been deepened by the passage of years and a greater

understanding of the message both of Jesus Christ and Mahatma Gandhi, that a

true Christian in India today must necessarily be a Gandhian. The corollary to

that, that a Gandhiite must also be a Christian, need not necessarily follow,

unless the term Christian is understood in its widest, perhaps its truest sense,

in the sense in which Gandhi, with his life-long devotion to Hinduism, is himself

a Christian.

" A true Gandhiite is essentially a Christian. If what is vital in Christianity is the message of the Master and its application to life then Gandhi is a true follower of Jesus. The story is told how the disciples of Jesus once came across a person doing good works in his name, who yet would not follow them; and they "forbade him because he followed not us". When the incident was reported to Jesus, the Master said: "Forbid him not; for he that is not against you is for you." Gandhi certainly is not only not against Jesus, but is definitely for him.

"For redemptive, suffering love is the central principle in Christianity and the manifestation of it in practice, and not the preaching of any dogma, is what is needed, is what will convince India of the truth and the power of Christianity. It ought to be a matter of supreme thankfulness to the Indian Christian that this principle is not unwelcome or alien to India; that it is the guiding light of India's leading statesman and has received at his hands a practical application on a scale unprecedented in world history. For it is one of the main theses of this book that Gandhi's satyagraha is Christianity in action and that the Christian Church lost one of its greatest opportunities in recent years in failing to fall behind Gandhi in his great movement for national emancipation on non-violent lines. This failure was largely due to the foreign leadership to which it is still so subservient."

His personal life was also in turmoil as his wife had to stay with her parents with their two small children while George went to Gandhi’s Ashram at Sabarmathi. That was the time when Gandhi was in prison. In one of his letters to George, Gandhi wrote… "Only do not give me up in despair…"

This appeal not to give him up in despair touched George and humiliated him. He wrote later: "Not only have I not givenhim (Gandhi) up, but I continue to draw inspiration from that fountainhead of light to humanity, groping and floundering along the path of violence in this age of atomic powers…"

George had to return to Kerala shortly afterwards following the death of his daughter to look after his wife who suffered from a sudden shock following the tragedy. It was the time when Gandhi had come to Trivandrum to preside over the celebrations of the Travancore Temple Entry. He made it a point to visit the ailing Mary George after the function inspiring her with his mere presence.

For George the going was not easy. He spent much of his time struggling to maintain his intellectual integrity and his right to exist even as an independent and unattached Christian. Many of the church-controlled institutions refused to provide him a job because of his freethinking religious ideas.

In 1942 George produced a small book Life and Teachings of Jesus Christ. Reviewing this book Sir C P Ramaswami Aiyar wrote: "It is impossible to improve on Mr. George’s account that the modern mind sees the evidence of Jesus Christ’s divinity not in his miracles in the fragrance of his sacrificial living…I have learnt more about the real character of Jesus from this book than from any other." Sir C P was the then Dewan of Travancore.

Gandhi appointed Mrs. George as his representative in the Kasturba Trust for Kerala, which started functioning in 1946, with a training centre at Trichur in the house and land belonging to the George family. Mrs. George worked as a representative for about 8 years.

From 1947-1950, George was in Viswa Bharati, Shantiniketan, as editor of Sino-Indian Journal and professor of English in their college and then as President, C F Andrews Memorial Hall for Christian and Western Studies.

The Fellowship of the Friends of Truth,which started in 1951 and whose Secretary for the first seven years was George,functioned as an inter religious movement.According to George,the place of Jesus in the Hindu heritage of India is as one of the Ishta Devathas or chosen or favourite deities.Hinduism readily grants such a place to Jesus.

In 1954, the then Madhya Pradesh Government appointed the Christian Missionaries Activities Enquiry Committee with Justice N B Niyogi as its chairman with five members. Prof S K George was one of them, the only Christian on the committee. A storm of protest was raised by a certain section of people against the very appointment of the enquiry committee, and specially directed against George.

He launched Gandhi Marg , a magazine in 1957.The work of the Enquiry Committee proved too much for George. The nervous strain of serving on such a commission could be imagined. " A very tired man", as he said to himself. He was suffering from Parkinson’s disease. There was no definite treatment for this progressive disease in those days. His health deteriorated. Meanwhile his wife died on 19th December 1959.George followed his wife a few months later on 4th May, 1960. He was sixty years old then.

To those who knew the man personally, it was a great loss. As Rev. R. R. Keithahn said: "George was ahead of most of us. He had rid himself of that which binds the spirit. He could look at another man, another religion, another thought as few men ever do. As a result, he could at once make the truth his own fettered by no dogma or ritual or prejudice…surely he was a man of God."

In 1954, the then Madhya Pradesh Government appointed the Christian Missionaries Activities Enquiry Committee with Justice N B Niyogi as its chairman with five members. Prof S K George was one of them, the only Christian on the committee. A storm of protest was raised by a certain section of people against the very appointment of the enquiry committee, and specially directed against George.

The force of opposition to George’s appointment can be well gauged by the necessity felt by the

Government of issuing a press note to justify the appointment of the Committee. With reference to George, the press note stated: " As regards Shri S K George, he is a devout Christian and a nationalist, belonging to the oldest Church in India- the Syrian Christian Church-and has been an educationist and a public worker of more than twenty five years’ standing. He has pursued Theological studies both in India and Oxford, and was also working in Shantiniketan. He has published several books on Christianity."

Government of issuing a press note to justify the appointment of the Committee. With reference to George, the press note stated: " As regards Shri S K George, he is a devout Christian and a nationalist, belonging to the oldest Church in India- the Syrian Christian Church-and has been an educationist and a public worker of more than twenty five years’ standing. He has pursued Theological studies both in India and Oxford, and was also working in Shantiniketan. He has published several books on Christianity."

He launched Gandhi Marg , a magazine in 1957.The work of the Enquiry Committee proved too much for George. The nervous strain of serving on such a commission could be imagined. " A very tired man", as he said to himself. He was suffering from Parkinson’s disease. There was no definite treatment for this progressive disease in those days. His health deteriorated. Meanwhile his wife died on 19th December 1959.George followed his wife a few months later on 4th May, 1960. He was sixty years old then.

To those who knew the man personally, it was a great loss. As Rev. R. R. Keithahn said: "George was ahead of most of us. He had rid himself of that which binds the spirit. He could look at another man, another religion, another thought as few men ever do. As a result, he could at once make the truth his own fettered by no dogma or ritual or prejudice…surely he was a man of God."

S K George was gentle as a saint but firm as a rock on all matters of principle, that was what had made his life’s pilgrimage such a difficult one. With his scholarship and flawless English he could so easily have led a peaceful and happy life in the pleasant backwaters of Christian colleges, had he been prepared to turn a deaf ear to what he called, in the title of his first book, Gandhi’s Challenge to Christianity and to hold aloof from national struggle.

Another Christian,Barrister George Joseph ( 1887 - 1938) from Kerala was just opposite to S K George-George Joseph,who was with Gandhi, distanced himself from him when he was asked to stay away from the Vaikam Sathyagraha by Gandhi. He was the editor of Motilal Nehru's The Independent and Gandhi's Young India.Instead of becoming a gandhian,he turned a Christian.

An anecdote from S K George:

In 1936, Gandhi went to Trivandrum to preside over a meeting to welcome the epoch-making

proclamation accepting the right of so-called 'untouchables' to worship at Hindu temples. I (S. K. George) went to call on Gandhi at his residence, but

could not see him. I met Mahadev Desai and told him about his wife who was ill at the

time. I spoke about it also to G. Ramachandran, another colleague of Gandhi's hailing

from Trivandrum, regretting our inability to meet Bapu. Ramachandran, knowing the mind

of the master, said that then it would be a case of the Mountain going to Muhammad. I

quoted scripture against that, and said that it was unworthy that he should enter under our

roof.

But what the disciple had predicted happened. After the great meeting that evening Gandhiji

returned to his residence, not joining in the procession that followed. During his evening

meal he asked about my wife and enquired where we were staying. It so happened that the

State Guest House where he (Gandhi) was staying was close to our house, and one of the

sisters in attendance on him was a teacher in our school. She offered to guide him to our

place; and so immediately after food, staff in hand, the old man set out to visit his humble

sister who, he had heard, was lying ill.

It was past nine, and we had retired early. Only a single kerosene oil lamp was burning in the

house. We had not slept, and I could distinguish the voice of Mahadevbhai who was one of

the company visiting us. I told my wife about this and heard Mahadevbhai remarking: "He

thinks it is only Mahadev." Looking out I saw Gandhiji and party at our gate. I immediately

rushed to open the gate which was locked. Gandhiji observed with a chuckle: "So you are

afraid of thieves." I mentioned to Gandhiji what Ramachandran had said, and referred to the

Biblical parallel of the Roman centurion telling Jesus that he was not worthy that the Master

should enter under his roof. "Aha!" retorted Gandhiji.

Coming into the house, I sought to detain him in the drawing room. But he had come to give

a courtesy call and put me immediately in my place saying. "I have come to see not you but

your wife." And he walked straight to her room. Sitting beside her cot he enquired about her

illness and the treatment she was having. I woke up our little son and brought him to Bapu for his blessing. It was a very patient and unhurried few minutes that he spent with us, but

we were a little too flurried to use it to the fullest advantage in seeking his paternal advice on

our problems.

(Source: "A Sick Visitation" by S.K. George)

Two other Christians associated with Gandhi were,K T Paul and S K Datta.After a long period as National Secretary of YMCA,Paul resigned that position so that he could be more active in politics.Paul alongwith Datta,represented the Indian community at the London Round Table conferences ( 1930-32) and there tried to bring reconciliation among the opposing leaders who took part.Paul knew Gandhi intimately and was associated with the prominent leaders between 1920 and till his death in 1931.

In 1937,the American Christian Rev Dr R R Keithahn asked Gandhi to explain the differences between religions. Gandhi answered:"The differences of race and skin and of mind and body ... are transitory.In the same way essentially all religions are equal."

© Ramachandran

No comments:

Post a Comment