He Upheld Land Reforms Act, Set Free Fr Benedict

While writing the Communist History of Kerala in 2013, I had to do a chapter on the Andhra rice scandal, which cropped up during the first EMS ministry in Kerala in 1957-1959. Justice P T Raman Nayar commission had enquired about it.I had to then write a personality sketch on him. He was the Judge who liquidated the Palai Central Bank in 1960, and ex0nerated Fr Benedict in the Mariyakutty murder case.

Justice P.T. Raman Nayar's seminal, trail-blazing judgments speak for him. The third Malayali Indian Civil Service officer,after M C B Koman and A S P Ayyar, to have become a Judge — and later Chief Justice — he won laurels for his erudition, and austere, if not manic, adherence to the rule of law.Koman was a Judge of the Madras High Court during 1945-1946.He belonged to the 1923 batch of the ICS. Raman Nayar was the only ICS Judge the Kerala Highcourt ever saw. He bacame a Judge in 1957 and was its Chief Justice from 1969-1971.

|

| P T Raman Nair |

I C S had a judicial branch-It is generally acknowledged that the ICS men in the Judicial Branch contributed significantly to both sustaining and enriching the Indian legal system, pre and post-1947. While only one, Kailas NathWanchoo (ICS, UP, 1926) headed the Supreme Court of India (1967– 68), several other ICS Judges have adorned that Court; the names of Justices SK Das, KC Dasgupta, Raghubar Dayal, V Ramaswami and Vashistha Bhargava come to mind. In Punjab, the first four Chief Justices, post-Independence, were from the ICS, namely Eric Weston, a European ICS, AN Bhandari, GD Khosla and Donald Falshaw, another European ICS, who left in 1966. In 1958, Justice H.K. Chainani (ICS, 1927) – approximately the same seniority as Justice KT Mangalmurti, ICS – succeeded MC Chagla as Chief Justice, Bombay High Court. Other ICS Chief Justices, RL Narasimhan in Cuttack, DE Reuben in Patna, MC Desai, VG Oak and Dhatri Saran Mathur (an engineering graduate from Roorkee) in Allahabad, NDK Rao in Hyderabad, Jagat Narain in Jodhpur, PT Raman Nair in Kochi and VB Raju in Ahmedabad have added lustre to the status and dignity of the judiciary in independent India.

M Anantanarayanan (ICS, Madras, 1929) retired as Chief Justice of the Madras High Court in 1969.Another contemporary, Justice V Ramaswami (ICS, Bihar & Orissa, 1929) was elevated to the Supreme Court in January, 1965.

Satyendranath Tagore, elder brother of the poet, the first Indian to win his way into the ICS, served in the judiciary in the then Bombay Presidency which covered parts of present-day Maharashtra, Gujarat and Sindh. The third Indian to join the ICS (in 1869), Behari Lal Gupta, became the first Indian Chief Presidency Magistrate of Calcutta, an appointment that sparked off a serious debate in regard to an Indian being appointed to this position in the colonial State, leading to the Ilbert Bill controversy of 1883; he retired as an Officiating Judge of the Calcutta High Court in 1907. The first two Indians to enter the ICS in the Madras Presidency became Judges – AC Dutt (District Judge, Cuddalore) and V Venugopal Chetti (District Judge, Nagapattinam).

In 1938-39, Ronald Francis Lodge (ICS, Bengal, 1910) was on a three-member Bench of the Calcutta High Court hearing the appeal in the sensational Bhawal Sanyasi case in which the majority view upheld the identity of the second Kumar, Romendra Narayan Roy; Lodge, who gave a dissenting judgment, went on to become Chief Justice of the Assam High Court in April, 1948 and, briefly, Acting Governor upon the demise of Sir Akbar Hydari.

Till India’s Independence in 1947, around one-fourth of the ICS officers served in the judiciary becoming, in time, District and Sessions and High Court Judges. The rationale of transferring an ICS officer after about ten years of service to the judicial cadre was to ensure that those entrusted with the responsibility of resolving disputes and dispensing justice had direct knowledge (having been Assistant Collectors and Sub-Collectors) of the ground realities and of matters of tradition and custom. Post – 1947, a few Indian ICS officers like Kerala Christian A L Fletcher (Punjab, 1933) who had been the District Judge, Gujranwala (now in Pakistan) moved from the Judicial Branch to the Executive, worked as Commissioner, Jullundur Division and had a long stint as Financial Commissioner at Chandigarh.

|

A L Fletcher

|

Anthony Leocadia Fletcher, son of Peter Fletcher and Helen Fletcher, was born on 9 December 1909 in a Christian family of Kerala. He completed his school education from St. Joseph's Higher Secondary School, Trivandrum. He did his B.Sc. from University of Madras and M.Sc. from University of Nagpur. Then he went to School of Oriental Studies for further education and joined as Indian Civil Servant in London,in 1933.

Fletcher was appointed the first Vice-chancellor of Chaudhary Charan Singh Haryana Agricultural University on 29 March 1970 and served until his death on 14 December 1974. He was also the founder of Campus School CCS HAU, Hisar present inside the university premises, a school that caters to the children of university employees. The administrative block of the University is named after him as Fletcher Bhawan. Nomenee Robinson, Michelle Obama's uncle has worked under him in 1961.Fletcher was married to Patricia Fletcher and had one son and two daughters.

Of the small number of European ICS officers who opted to serve on the Indian side of the Radcliffe Line, a few were in the High Courts, such as Basil Reginald James (1954 – 60) and William Broome (1958 – 72), son-in-law of Sir Hari Singh Gour (eminent jurist and founder of Sagar University) at Allahabad. When a vacancy of Chief Justice occurred in the Nagpur High Court in the early fifties, a replacement was brought in from Patna, since the senior most puisne judge, CR Hemeon, a European ‘nominated’ to the ICS (in recognition of ‘war service’) was found to be “not good enough to be promoted as Chief Justice and not bad enough to be superseded in his own Court”.

The image of the ICS officer as ‘ruler’ runs through many accounts of British Raj in India. While the Executive and Judicial branches of the Service had a clear demarcation of functions, they maintained, in broad terms, a common identity; the ICS origins were always important. On the judicial side, there were distinguished personalities like Sir B N Rau (ICS, Bengal, 1910) who served in the Calcutta High Court and, later, as Constitutional Adviser to the Constituent Assembly, Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir State,as also Judge of the International Court of Justice at The Hague.

KVK (Kalyana) Sundaram (ICS, CP & Berar, 1927) displayed such legal ability at an early stage that the Judicial Commissioner, Sir Robert McNair, later commented that “Sundaram was one of the few junior legal officers whose recommendations he would take in disposing of a case without appraising it himself”. Sundaram was appointed as Union Law Secretary in 1948 and was, thereafter, the second Chief Election Commissioner of India.

The High Courts had an array of ICS officers. Among them were Justices Sir Barjor Jamshedjee Dalal (1925-31), Harish Chandra, S B Chandiramani, Atma Charan (he was the Special Judge in the Mahatma Gandhi murder trial), B N Nigam at Allahabad, Justices ASP Ayyar (Ayilam Subramania Panchapakesan Iyer-an eminent literary figure and father of former Foreign Secretary, AP Venkateswaran), K Srinivasan Iyer at Madras, HR Krishnan in Bihar (and Indore in Madhya Pradesh) and S S Dulat in Punjab. Justice AK Mukherjea (Judge, Supreme Court, 1972-73) who joined the ICS in 1937 and worked in the Ministry of Transport, Government of India, and as Secretary, Radcliffe Commission, opted for premature retirement in 1951; later, he returned to judicial service as a puisne judge of the Calcutta High Court.

While the ICS members of the higher judiciary in the subcontinent did not exactly set the Thames on fire, their integrity and sincerity were unchallengeable. Some of the very highly regarded personalities at the Supreme Court of India – Justices Patanjali Sastri, BK Mukherjea, Vivian Bose, Gajendra Gadkar, Hidayatullah, JR Mudholkar, SM Sikri and VR Krishna Iyer, illustratively speaking – had no links with the ICS.

One ICS District Judge (IM Lall) faced compulsory retirement; Justice SB Capoor of the Punjab & Haryana High Court was among the last ICS members to leave in the late sixties.

Like Fletcher,the legendary A S P Ayyar is never identified as a Malayali,but his son A P Venkateswaran,was referred to as a Malayali.A S P Ayyar ( 1899-1963 ) was born at Ayilam,a Palakkad hamlet.K P K Menon has written a biography of him.He himself wrote his service story-Twenty five Years as a Civilian.He presided over the Alavandar murder case.

|

A S P Ayyar

|

P T Raman Nayar's court was even a greenhorn's tutorial. “Regardless of seniority, he would patiently hear you out. For beginners like me, appearing before him was really an educative experience,” remembered K.A. Nayar, a former Judge of the High Court.

“[He] did not make any distinction between senior and junior lawyers and he knew only about good and bad cases,” the former Kerala High Court Judge, V. Bhaskaran Nambiar, who had appeared before Raman Nayar as an advocate, writes in his memoirs, Life's Likes and Dislikes.

Raman Nayar expected lawyers to be thorough with his or her case. Anyone caught wanting in facts or advocacy would face terse, but intelligent, comments from him. But he would not be incensed by a repartee.

Whenever a question involving a section of the Civil Procedure Code or an Act came up, before hearing the lawyer on the interpretation he would reach out for the Act or Code and read the section over and over again before engaging the lawyer in a discourse and arriving at a conclusion.

Remembered Senior Advocate T.P. Kelu Nambiar: “Even if on the same day the same question pertaining to the same section had come up, he would repeat the process. When I asked him about this, he explained: ‘When we interpret a section in the background of a case, we get a perspective, but the same section read in the backdrop of a new case may throw up a whole new perspective'.”

Born on January 14, 1910, Raman Nayar hailed from Kumaranellur,Palakkad. He was the cson of Padinjarankunnath Thazhethayil Lakshmi Amma and Kinattinkara Krishnan Nayar.After schooling at Mangalore, Kakinada, Kozhikode and Madras, he graduated from the Madras Law College. He cleared the ICS in 1932 while an apprentice-at-law under O.T.G. Nambiar in the Madras High Court.

After probation at Cambridge, he held the posts of Assistant Collector, Sub Collector, City Magistrate, Additional District Sessions Judge and District Sessions Judge in places like Chengsalpet and Tiruchirapally in Tamil Nadu, and in Mangalore. He became Registrar of the Madras High Court. He was Joint Secretary to the Law Ministry when Dr. B.R. Ambedkar was Law Minister. Later he was Special Secretary overseeing State reorganisation in Kerala.

In 1957, Madras High Court Chief Justice P.V. Rajamannar nominated him a Judge of the Kerala High Court.After the states reorganisation,Nayar had opted for Kerala.

|

| Fr Benedict Onamkulam |

In the Mariyakutty murder case — Raman Nayar later termed it the most difficult in his career —he acquitted the accused, Fr. Benedict Onamkulam, a Catholic priest who had been convicted by a District Court. The District Court had reservations about the investigation, but took a ‘serious view' as the accused was a priest. Raman Nayar upheld the principle of equality before the law and exonerated him.Nayar was proved right when in 2001,wife of the real ciulprit confessed to Fr Benedict.The culprit had died and Fr Benedict,who was in his 80s had returned from the US.It seems the priest had kept the confession of the culprit as a secret.

Mariyakutty case or Madatharuvi case involved the 1966 murder of a widow named Mariyakutty. A priest, Fr. Benedict Onamkulam, was convicted of the crime. Sessions court sentenced the priest to death but the Church approached the high court and freed him. His supporters claim that he knew the culprit, but he didn't break the seal of confession.The prosecution alleged that the Syro-Malabar Catholic priest Fr. Benedict Onamkulam had killed Mariyakutty at the stream of Madatharuvi, near Ranni with the motive of ending their affair. Onamkulam was sentenced to death by the session court, however, the High court of Kerala acquitted and freed him purely based on technical grounds dismissing circumstantial evidence in 1967.

The case has been so sensational in Kerala that it inspired a number films. It came into prominence in local media again in 2010 when the Changanassery Bishop opened Fr. Benedict's tomb for prayers at Athirampuzha,Kottayam.

Raman Nayar's commission of inquiry report into the Andhra rice deal provided fodder to the ‘liberation struggle' that led to the dismissal of the first elected Communist government. EMS had apologised in a contempt of court case in 1958.Nayar penalised E.M.S. Namboodiripad in, who was Chief Minister for a second term, in a contempt of court case in 1968,for his statement that the judiciary was “guided and dominated by class hatred, class interests and class prejudices and where the evidence is balanced between a well-dressed, pot-bellied rich man and a poor, ill-dressed and illiterate person, the judge instinctively favours the former.”

The first state government led by E. M. S. Namboodiripad was rocked by the infamous Rice Scandal that pertained to alleged corruption in the purchase of rice from Andhra Pradesh. During the summer of 1956,the government imported 5000 tonnes of rice from a wholesale dealer,M/s T Sriramulu,P Suryanarayana & Co.It was done without tenders.This deal was suggested by the then Lok Sabha member A K Gopalan and it is said that the kick back in the deal was diverted to the Andhra elections where the Communist Party expected to win; P Sundarayya had gone to Andhra from Delhi to lead the campaign,expecting to win and becoming the CM.

T. O. Bava of the Congress raised the allegation that the purchase made without floating tenders caused a loss of Rs 16.50 lakh to the exchequer. K. C. George was the then food minister. A probe was ordered under the Commission of Inquires Act, 1952 and Justice P. T. Raman Nayar was the inquiry commission. Though the commission’s report confirmed the monetary loss, it also suggested that no one in the ministry made any personal gains. The government tabled the report in the Assembly, but with a dissent note and rejected the demand for K. C. George’s resignation.EMS government rejected the Raman Nayar commission report.

|

| K C George |

Though branded an anti-Communist, he upheld certain vital provisions of the Kerala Land Reforms Act as “it passed the test of law.” Amid opposition from lawyers, he instituted the list system under which cases pending hearing would be posted for a particular day and no adjournment would be allowed.

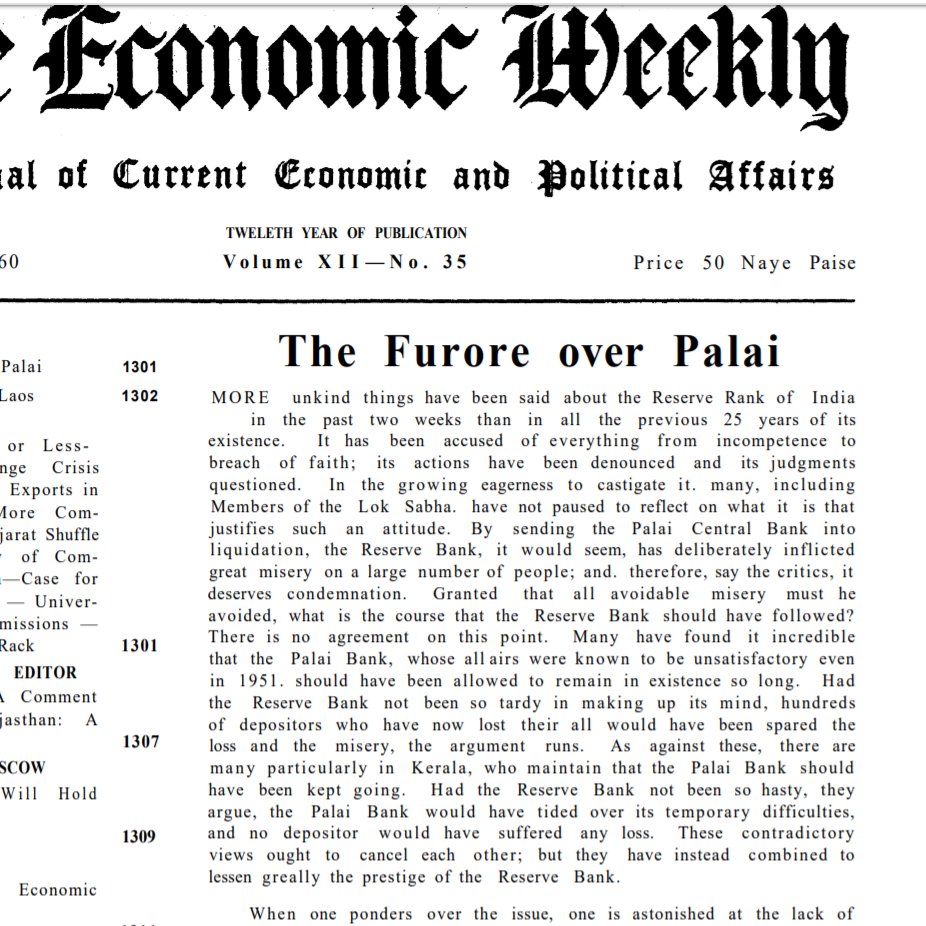

Among his judgments were the one liquidating the Pala Central Bank in 1960. Said Senior Advocate C.M. Devan, who represented the Reserve Bank of India in the case: “Justice Raman Nayar … did everything to protect the interest of investors. His legal acumen stood out.” The incisive, lucid judgment was dictated soon after arguments ended. Raman Nair rarely reserved judgments.

From the time of its founding in 1927, Palai Central Bank had an eventful history.Although it was started in a small remote city, the bank grew up to become not only the biggest bank but the biggest institution in Kerala, after the state government, and the 17th largest among the 94 scheduled banks in India.

Joseph Augusti Kayalackakom founded The Central Bank Limited in (Pala), a small town in the central part of the then native state of Travancore, which later became part of Kerala. His uncle, Augusti Mathai Kayalackakom, provided the start up capital. Joseph Augusti, who belonged to a family of agriculturists and traders, had carried on some other businesses before going into banking. He had run textile business initially in Pala, and later on in Thiruvananthapuram (Trivandrum) in 1908; he also established a bus service in Thiruvananthapuram from 1910 onwards.

The bank was incorporated under the Travancore Companies Regulation (1092) with the following persons as the initial Promoter-Directors:

- Chairman: Augusti Mathai Kayalackakom

- Mg. Director: Joseph Augusti Kayalackakom

- Directors: Outha Ouseph Thottumkal, Varkey Ouseph Vellookunnel, Cheriyathu Thommen Menamparambil, George Joseph Kottukappallil and Jacob Cherian Maruthukunnel

In 1929, when the Great Depression struck and Travancore's plantation sector was badly hit, the bank gave liberal assistance to the plantations. The bank, which later changed its name to Palai Central Bank, started expanding its activities by opening branches at several places. When the Bank opened a branch in New Delhi, India's new capital city in 1932, it was the very first bank to do so, ahead of even the established north-Indian banks. The Bank also discovered the potential of Aluva (Alwaye) by opening a branch there.

In 1935, the bank introduced electricity in its head office building in Pala by installing oil-powered generator, years before Government's first power project was commissioned at Pallivasal.The bank's managers, KM Joseph and later KM Augustine in Thiruvananthapuram, George Joseph in Chennai (Madras), KM Chacko in Nagercoil, C J Thomas in Delhi and others enjoyed exceptional popularity and influence.

|

Joseph Augusti

|

In 1935, George Thomas Kottukapally, the brother of Director George Joseph Kottukappally, became a Director of Palai Central Bank. As the Travancore Debt Relief Act was coming into existence in 1937, one of the first directors of the bank, Jacob Cherian Maruthukunnel, was nominated to the Sree Chitra State Council to pilot the relative Debt Relief Bill, as it was expected that banks would be affected by the Act.

In 1937, two of the major banks of Travancore – Travancore National Bank and Quilon Bank merged to form Travancore National and Quilon (TNQ) Bank. However, in the very next year it was liquidated . This led to the collapse of more than 60 small banks. However, Palai Central Bank, which was the leading bank then, remained unaffected.

With India's independence in 1947, the first popular government assumed power in Travancore in 1948 with Pattom Thanu Pillai as Chief Minister. The new Chief Minister told the bank's management that the bank could make a major contribution in nation building. The bank subscribed to government bonds for large amounts.The bank financed the construction of the Trivandrum-Nagercoil Cement Concrete Road, which now forms part of NH-47.

In the 1940s the Bank enjoyed an unprecedented financial position and influence. I took the chief editor of Malayala Manorama Daily, K M Mathew to the Surya TV studio in 1998 for an interview in which he spoke on the Palai Central Bank management helping their founder Mammen Mappilai – who was struggling to revive the newspaper – by offering to take over the paper as a whole or to invest in its shares, as a friendly gesture of Joseph Augusti towards a close family friend. Eventually, an investment of 20% in shares was made.

In 1948, K M Joseph Kayalackakom – who had become a Director of the bank in 1940 following the death of his father and the first Chairman of the Bank, Augusty Mathai – moved from Trivandrum to the bank's head office at Pala. He became the virtual General Manager of the institution.

In 1947, at a time when there were no management schools anywhere in the British Empire, Joseph Augusti sent his cousin KM George to the United States for management studies. KM George took his MBA degree from New York University in 1948, thus becoming the first MBA degree holder in Travancore. In 1949, he joined the bank as an executive. He was to later become the Secretary and chief executive officer of the bank.

In the late forties it was found that during the previous few years, the institution had drifted and slowed down from its previous spectacular growth rate. Officials, who had the charge of advances, had not been successful in controlling subordinates sufficiently to ensure discipline over making of advances. Several advances had proved to be doubtful, although their percentage in total advances was not high.

In 1949, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) was nationalised and the Banking Companies Act came into existence (later renamed as Banking Regulation Act). This legislation gave RBI complete control over commercial banks. As RBI entered the picture, it continuously pursued the question of the old doubtful advances of the bank.

Like the TNQ bank,Palai Central Bank too had a Christian agenda. In 1950, when a new Diocese of the Catholic Church was formed in Pala, it was an open secret that the bank was the prime mover in bringing the Diocese to Pala. Joseph Augusti led a delegation that accompanied the new Bishop Mar Sebastian Vayalil to Rome for the investiture ceremony. The bank also took keen interest in extending assistance to the initial ventures of the new Diocese of Palai.It financed the St Thomas College, Alphonsa College and the Bishop's palace, without collateral. In 1953, the Bank accorded a grand reception to Eugene Tisserant, Dean of Vatican's Sacred College of Cardinals, at the residence of the managing director in Palai during the Cardinal's visit to Kerala.These were not banking,but were communal activities.

|

| Palai Central Bank was a pioneer in modern ads |

In 1953, George Thomas Kottukapally, who was still a Director of the bank, became a member of parliament. Even after that, he continued to be a director. In the same year, when A. J. John (who had become Chief Minister of the integrated Travancore-Cochin State) resigned, he accepted the bank's invitation to join its board of directors.

In January 1955, the ruling Indian National Congress party, at their national conference held at Avadi in Tamil Nadu, passed the resolution to establish socialism in India "where the principal means of production are under social ownership or control". As the implementation of this began and the nation started moving along the socialist path, in that year itself Government of India nationalised the Imperial Bank of India and formed State Bank of India. In January 1956, life insurance was nationalised and Life Insurance Corporation of India was formed.

Palai Central Bank had by then emerged not only as the biggest enterprise in Kerala – bigger than all the private and public undertakings and banks in the State – but also as the 17th largest bank in the country, bigger than even some of the State banks. From 1956 onwards RBI started turning down the Bank's repeated requests for opening new branches. In 1956, when RBI asked for the communal break-up of the Bank's depositors.

In March 1957, H V R Iyengar became Governor of RBI. He had succeeded B Rama Rau who had resigned due to differences with the Finance Minister after a long period of nearly eight years in office. In Delhi, Jawaharlal Nehru's two finance ministers had resigned in quick succession and Morarji Desai became the new Finance Minister in March 1958.

In 1959, seven banks controlled by the erstwhile native states – including State Bank of Travancore – were nationalised by Government of India and made subsidiaries of State Bank of India. Towards the end of that year RBI, initiated a series of steps in Palai Central Bank. It asked Joseph Augusti to retire from the board of directors of the Bank. K M George was asked to step down from the post of chief executive officer and to continue as Secretary of the Bank. An official of the State Bank of India was appointed as the bank's new chief executive officer. Following these moves, some of the bank's depositors lost confidence in the institution.

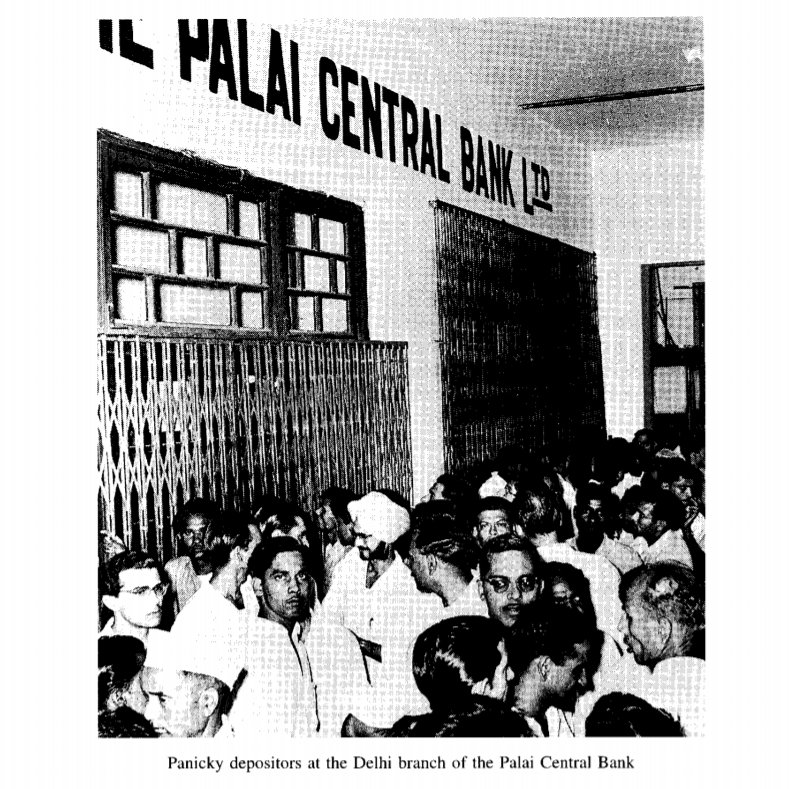

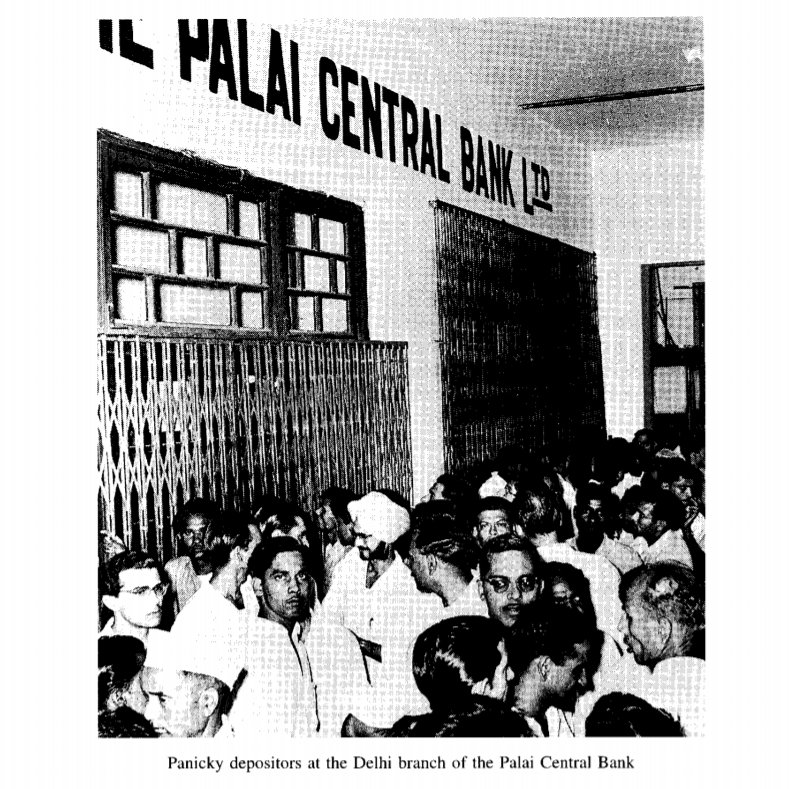

In 1960 February, a new ministry assumed office in Kerala with Pattom Thanu Pillai as Chief Minister. In August that year, the Governor of RBI succeeded in persuading Desai for the closure of Palai Central Bank which, he told him, had too much of doubtful advances.RBI moved the application in Kerala High Court for the winding up of the Bank under Section 38(3) (b) (iii) of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949. The Banking Regulation Act does not allow the High Court to go into the merits of RBI's application but specifies that the Court "shall order the winding up" if an application is made by RBI. Also, RBI can move an application if in the opinion of the RBI "the continuance of the banking company is prejudicial to the interests of its depositors". Justice P T Raman Nair, the presiding Judge of the Kerala High Court ordered the winding up on 8 August 1960.

When a group of Kerala MPs met Nehru requesting that the bank be revived, he told them that he would like to, but his insistence will lead to the resignation of Desai. He said there is a feeling that Finance Ministers did not thrive under him and so he did not want another resignation. In the larger interests of the nation, he asked the Kerala MPs to put up with the whole thing. When Chief Minister Pattom Thanu Pillai met Desai to make a personal appeal, he cut him out by asking as to how much money he had lost. A furious Pattom Thanu Pillai told him that like Desai he was also a true Gandhian and he has never had a bank account in his life. He then angrily walked out. With that, all doors for a revival from Government side were closed.

A legal battle was then fought. But the delay of the legal process made a revival impossible. In the Supreme Court, the Bank's case was argued among others by Gopal Swarup Pathak, who later became Vice-President of India. The Court ruled in a 3–2 judgement that with the delay, a revival has been rendered infructuous.

The Finance Minister of the country stated in Parliament that the bank's deposits had hardly 15% asset backing,;the people had no reason to disbelieve.The depositors got more than 90% of their money – but in petty instalments.Desai said that,after the collapse of the bank,withdrawls increased steadily from Rs 12 lakh during the week ending 1 July 1960 to 17 lakh a week later,20 lakh during the week ending 15 July,23 lakh,29 lakh,35 lakh during the weeks ending 22 July,29 July and 5 August.

In the early 1990s when banks in India faced a crisis of mounting losses and high levels of non-performing assets, an interviewer asked a now-retired Justice P T Raman Nair about his thoughts on the winding-up order of Palai Central Bank three decades ago. He then remarked that today's banks were in much worse condition and that if the current yard stick were applied Palai Central Bank would not have been ordered to be closed.That doesn't mean Palai bank fared better or Ramn Nair's ruling was wrong.Infact,he did right-In 1964, barely 3 years after the closure of Palai Central Bank, a major upheaval occurred in the Congress Party in Kerala. Fifteen of its MLAs – mainly those from central Kerala – split and formed a new party, Kerala Congress.The closure of Palai Central Bank is considered by many to be one of the root causes that led to the new chain of political events.

|

| Panicky depositors at Delhi Palai Central Bank |

Raman Nayar led a simple life and steered clear of any inappropriate social engagement. “An able administrator and a highly-regarded jurist, he was really generous when praise was due,” recalled M.C. Madhavan, former Registrar of the Kerala High Court. He was personal assistant to Raman Nayar as Chief Justice.

He was not elevated to the Supreme Court. ‘Social justice' had become the buzzword in the late-1960s. Around this time, he gave a speech at Tiruchi in which he remarked that although everyone was so obsessed with socialism, the word did not find a mention in the Constitution. That speech, it is believed, cost him dear. (The word ‘socialist' was later added to the Constitution through the 42 Amendment,during the Emergency.)

K.S. Paripoornan, former Judge of the Supreme Court, said: “Justice never suffered at the impartial hands of Raman Nayar. By not promoting him to the Supreme Court, the country became the loser.”

Raman Nayar ‘retired hurt', on September 1, 1971 — four months before completing his term. H.R. Gokhale, Law Minister in the Indira Gandhi-led government, reportedly conveyed to him Chief Minister C Achutha Menon's displeasure at not being consulted while nominating judges for appointment in the High Court.Obviously,Menon had conveyed his displeasure to Indira Gandhi. The constitutional provision for appointment of judges to the High Court stipulated that the Chief Justices send their recommendations to the President through the Governor. Raman Nayar proceeded on leave.It should be noted that Menon,Member in Rajya Sabha was imported to Kerala as Chief Minister of a Congress led government.It was back door politics at the behest of the Soviet Union.Menon,who belonged to the Soviet led CPI was a stooge of Indira Gandhi by enjoying her generosity.He paid by the excesses committed by the police during his term in Emergency.

It is also said Menon was irked by the suggestion of Indira Gandhi and Gokhale in a meet of Chief Justices that the Juduciary should have a social face.His motto was,"I am not a law maker.My duty is to interpret the written law.I should not fail in it."

When once he was invited by the Nair Service Society to be the chief guest at their meet,Nayar refused feeling that the invitation came because he was a Nair.He asked the NSS office bearers to invite Justice K T Koshy.

He was a Gandhian even during the British rule and wore khadi always,except in court.He said about communism in Kerala:"There is communism both in Punjab and Kerala ( Harkishan Singh Surjeet,a Punjabi was CPI ( M ) General Secretary ).While a man in the street in Punjab aspires to be a car owner by hard work,here the tendency is to get the car owner into the street".

He drove his own car to the market,never exploiting public exchequer.When his car was once blocked by a traffic police man,Nayar stared at him."You are behaving as if you are a judge",the police man freacted.Nayar was the Chief Justice.

Until his death in 2003, Nayar kept himself updated with all that was happening around him. “Our regret is that he did not pen anything for posterity…,” said his son, Major General (retd) I. Krishnan. But posterity will remember him.

© Ramachandran