"You have not cared to inquire into my past," BR Ambedkar wrote to his fiancée Sharda Kabir in February 1948. "But it will be available to you at any time in the pages of many Marathi magazines." Thus, in a terse statement, the towering leader of the untouchables dismissed his private preoccupations, almost like an afterthought, and put a premium on the recorded instances of his biography in the public domain.

|

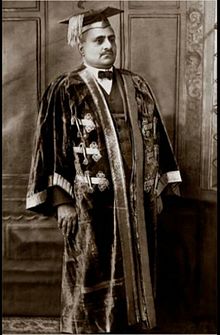

| Ambedkar,1952.On his way to Columbia University |

Savita Bhimrao Ambedkar or Sharada Kabir (1909 – 2003), was a doctor and the second wife of Babasaheb Ambedkar, the father of the Indian Constitution.

In Ambedkar's various movements, during the writing of the books, Indian Constitution and Hindu code bills and Buddhist mass conversion, she helped him from time to time. Ambedkar credited her in the preface of his book The Buddha and His Dhamma for extending his life for eight-ten years.

|

| Savita |

Savita was born in Bombay in a Marathi Brahmin family. Her birth name was Sharada Kabir. Her mother was Janaki and her father was Krishnarao Vinayak Kabir. Her family were a resident of Doors village, located in Rajapur of Ratnagiri district, Maharashtra. Later, her father came from Ratnagiri to Bombay. On Sir Rao Bahadur C. K. Bole Road, near the pigeon in the west of Dadar, the Kabir family rented Sahru's house in Matruchaya.

Sharda was a brilliant student. Her early education was completed in Pune. Around 1937 she did MBBS from Grant Medical College, Bombay. When her studies were completed, she was appointed as the first-class medical officer in a major hospital in Gujarat. After a few months of illness, she left her job and returned home. Her six of eight siblings had inter-caste marriages. Those days it was an extraordinary thing for Marathi Brahmins. Savita said, "Our family did not oppose inter-caste marriages, because the whole family was educated and progressive."

At Vile Parle, Dr S.M. Rao had close links with Ambedkar. When Ambedkar came from Delhi to Bombay, he often used to visit the doctor. Sharda Kabir also used to visit Dr Rao's house as she had a family relationship with him. One day both met at Rao's home.

The second meeting took place in the Advice Room of Dr Mavalankar. Ambedkar had blood pressure, blood sugar and joint pain at that time. In 1947, during the writing of the Indian Constitution, Ambedkar got health-related problems due to diabetes and high blood pressure. He did not sleep. having neuropathic pain in the legs,; insulin and some homoeopathic medicines could provide relief to some extent. He went to Bombay for treatment. Sharada came closer to Ambedkar during treatment.

On 15 April 1948, when they became a couple, she was 39 and he was 57. After their marriage, she was popularly called "Mai" (mother) by his followers. As Registrar for marriage, Rameshwar Dayal, Deputy Commissioner, was called into Delhi. It was completed as a Civil Marriage under the Civil Marriage Act. Among those who attended the occasion were Rai Sahab Puran Chand, Macy (Private Secretary), Neelkanth, Ramkrishna Chandiwala, Estate Officer Meshram, nephew of Chitre, his wife, Sharda Kabir's brother, and Home Secretary Banerjee. The then governor-general of India, C. Rajagopalachari, invited them for a Sneh Bhoj and greeted them. Sharda adopted the name Savita. Ambedkar used to call her, "Shārū".

On Ashok Vijaya Dashami (The Day on which Buddhism was accepted by Emperor Ashoka ) 14 October 1956, Savita accepted Buddhism along with her husband in Deekshabhoomi, Nagpur. She was given the initiation of Buddha's Dhamma by the Burmese Bhikkhu Mahastavir Chandramani giving Three Jewels and Five precepts. After this, Ambedkar himself initiated his followers to Buddhism. Savita Ambedkar became the first woman to accept Buddhism in this movement.

Many people from Delhi came to meet Ambedkar at 26, Alipur Road when he was sick. It wasn't possible that everyone will get a glimpse. Savita had to perform the dual duties of a wife and doctor. Ambedkar's health was steadily getting worse. She continued her care with full devotion till he breathed his last. After Ambedkar's death, his close friends and followers removed Ambedkar's acknowledgement of her help, from the book, Buddha and his Dhamma. After the death, some Ambedkarites blamed Savita for killing him. Rumours were spread that she had been giving slow poison.

The irony is that the people who are fighting against the caste system are becoming casteists. If Brahmin women refuse to marry Dalits, you would say it is casteism. If she does then you would say it is a conspiracy.

Ambedkar was already suffering from diabetes and ill health before marrying Savita. His health was deteriorating because of the heavy work and responsibilities on him. He was organising Dalits throughout the country. He has been involved in research-orientated works and publishing books. His economical condition was also not good. In his busy schedule, he didn't have time to take care of his health. Even Mrs Rama bai died of illness.

Savita knew the health conditions of Ambedkar before marrying. Since 1955 Ambedkar's health deteriorated further and faster. On medical advice, his teeth had been extracted long before. While getting up and moving about in the house he would require support. He had also trouble to breathe. An oxygen cylinder was purchased and he was given oxygen off and on But this was kept secret as Ambedkar feared that his followers would take fright at this news. Later he was given oxygen twice a week. In winter his body was given warmth by a heating apparatus. Sometimes he was also given an electric bath. Western type of food was also tried for his health but it was not to his taste and the arrangements for having such food prepared for him had to be discontinued.

After the demise of Babasaheb, when Nehru and Indira Gandhi offered Savita a Rajya Sabha seat, while they were Prime Ministers, she adhered to her husband's principle, rejecting the offer thrice.

Republican Party of India leaders Ramdas Athavale and Gangadhar Gadhe returned her to the mainstream Ambedkarite movement. The young activists of the Dalit Panthers movement treated Mai with respect. Again, she got separated from them. The posthumous Bharat Ratna for Ambedkar was received by Savita from President R Venkataraman on 14 April 1990.

She died in Mumbai on 29 May 2003.

Ambedkar himself did not shy away from acknowledging his relationship with 'F', as he referred to her. One of his most serious works, What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables (1945), a trenchant critique of Gandhi and the Congress, is prefaced by a long dedication which ends: "To F., In Thy Presence is the Fullness of Joy."

In 1921, the 30-year-old Bhim Rao resumed his doctoral studies at the London School of Economics and pursued Law at Grays Inn. Dependent on financial assistance, he lived the first year very frugally. His lodging was a room in a house in the Primrose Hill area of northwest London. It is this 2,050 sq ft three-storey six-bedroom house with a terrace that the Maharashtra government acquired in 2015 for close to Rs 40 crore.

What Ambedkar biographers know already is that the two met at the British Museum in 1920. In July 1920, he left for London with a loan from Shahu Maharaj to complete his studies. According to his biographer Dhananjay Keer, Ambedkar had to go to work with little food; "the keeper of the boarding house was a harsh and terrible lady". He moved from this to another boarding house, apparently that of Frances or her mother. After Ambedkar's return to India, Frances began corresponding with him in 1923, addressing him often as 'My darling Bhim'. She was instrumental in shipping a lot of books to Ambedkar and in sourcing material from the India Office library.

What is evident from a letter published in Khairmode's biography is that Ambedkar had suppressed his marriage to Ramabai from Frances. In 1905, Ambedkar, then 14, was married to nine-year-old Ramabai (who died in May 1935). Expressing concern over Ambedkar overworking himself, Frances wrote on March 11, 1925: "It is not as if you had a wife and family depending on you." Ambedkar chose to make this letter public in his own lifetime.

In 1923, when Ambedkar returned to India, Frances began writing to him; they stayed in touch until 1943 when her plans to come to India were disrupted. She was denied a visa because of "the political situation".

Having declared in 1936 that he was born a Hindu but shall not die one, Ambedkar had faced bitter criticism from the pro-Congress press of the time. There were even news reports in January 1937 that Ambedkar was to return from England having "secretly married an English widow." Ambedkar, of course, never married Frances, who died in 1945.

|

| Ramabai |

Ramabai was born in a poor family to Bhiku Dhatre (Valangkar) and Rukmini. She lived with her three sisters and a brother, Shankar Dhutre, in the Mahapura locality within the village of Vanand near. Her father earned his livelihood by carrying baskets of fish from Dabhol Harbour to the market. Her mother died when she was young and, after her father also died, her uncles Valangkar and Govindpurkar took the children to Bombay to live with them in the Byculla market.

Ambedkar married Ramabai, soon after he cleared the matriculation examination. He was a student at Elphinstone High School at the time. Ambedkar’s father Ramji Subedar had settled his son’s marriage with Ramabai. The wedding ceremony was held at the Byculla Bazar (Machhli Bazar) of Bombay. The groom’s family assembled at one corner of the market and the bride’s at another. Filthy water was gushing down a drain near the platform on which the rituals were performed. Ramabai was the youngest daughter of her parents, who had died when she was a child. Her father Bhikku Dhutre (Valangkar) had been from Vanand village near Dabhol and worked as a porter at the Dabhol port. She and her brothers and sisters were brought up by their relatives. Her brother’s name was Shankar Dhutre. (Dhananjay Keer, 2018, p 23).

Ramabai’s maiden name was Ramibai. After marriage, she was renamed Ramabai. Ambedkar’s followers addressed her as “Ramayee”.

Though Ambedkar and Ramabai married in 1908, they actually started living a married life only in 1917, after his return to Bombay from London. It was an occasion for celebration. Ramabai thought that her pain and miseries would soon end. Her Saheb would get a job, earn money and everyone would live happily. She hoped that they would have more children (the first child Gangadhar had died by then) and lead a happy, contented and prosperous life (Khairmode, 2016, p 112).

Testing times frequently visited the Ambedkar couple. The first time they found themselves in trouble was when Ambedkar went to London for the second time in 1920 to complete his studies. Before leaving, he left some cash with Ramabai for the household expenses but that did not last long and she had to manage with the meagre earnings of her brother Shankarrao and younger sister Meerabai. They could barely bring home 8-10 annas (50-60 paise) a day by doing odd jobs. She used the money for buying provisions and tried to somehow fill the stomachs of the family members. Those were difficult times for her. There were days on which they had to sleep on empty stomachs (Vasant Moon, 1991, p 25).

While Ramabai was struggling to arrange two square meals a day for the family in India, Ambedkar was no better off in faraway London. Ramabai wrote to him, describing the pitiful economic condition of the family. Ambedkar replied to her in these words:

|

How the two of them sacrificed their personal happiness and peace on the altar of social work was described by Ambedkar in an editorial on 3 February 1928 in Bahishkrit Bharat thus: “This writer [Ambedkar], who wrote 24 columns for Bahishkrit Bharat for a year for spreading social awareness without getting a penny in return and who, while doing this, did not care about his health, happiness and peace – she (Ramabai) made him the cynosure of her eyes. That is not all. When this writer was abroad, she carried the burden of the family on her shoulders and still does that. Even after this writer was back from overseas, she did not flinch in carrying basketfuls of cow dung on her head during periods of financial distress. And this writer could not find even half an hour in 24 hours for this extremely affectionate, amiable and venerable wife” (Prabhakar Gajbhiye, 2017, p 152).

This editorial was written to mark the completion of one year of the publication of the newspaper, titled, “Is Bahishkrit Bharat’s debt, not public debt?”

Ramabai and Ambedkar were dealt one cruel blow after another when they lost their three sons and a daughter. His son Gangadhar died when he was studying in America. Later, Yashwant was born, followed by Ramesh, Indu and Rajratna. The latter three also passed away. The loss of their four children left Ramabai and Ambedkar heartbroken. It looked like the family of Karl Marx, who has lost his children one by one in poverty. Ambedkar shared his pain in a letter to his friend Dattoba Pawar with heart-wrenching words:

| Home in London where Ambedkar stayed |

Ramabai died on 27 May 1935 at Rajgruha in Hindu Colony, Dadar, Bombay, after a prolonged illness.

After Ambedkar’s return to India, the economic condition of the family improved. But Ramabai’s health started deteriorating. Ambedkar’s biographer Dhananjay Keer writes:

She often had to starve in the initial years of her marital life, and that had broken her body. The death of four children had broken her heart. On 27 May 1935, Saheb’s Ramu bid farewell. Ambedkar had returned home the night before her death. He was by her side when she died. A morose Ambedkar, with his heart heavy with sorrow, walked haltingly with the funeral procession. After returning from the funeral ground, he locked himself up in a room. He cried like a child for a week after Ramabai’s death (Dhananjay Keer, 2018, p 239).

She had been married to Ambedkar for 29 years. Ambedkar's book, Thoughts on Pakistan, published in 1941, was dedicated to Ramabai. In the preface, Ambedkar credits her with his transformation from an ordinary Bhiva or Bhima to Dr Ambedkar. The dedication read:

“Inscribed to the memory of Ramu

As a token of my appreciation of her goodness of heart, her nobility of mind and her purity of character and also for the cool fortitude and readiness to suffer along with me which she showed in those friendless days of want and worries which fell to our lot.”

|

| Dhamma Diksha ceremony, Nagpur,14 October 1956 |

As the "ephemera of his life" keep flowing in, Ambedkar steps out of the aura of sainthood bestowed on him by history — revealing blind spots, prejudices, a mercurial temper and often fragile humanity.

The adulation Ambedkar got from the poor was extraordinary. On a visit to Nagpur in 1942, for instance, a group of "women in tattered saris" accosted him with garlands of marigolds. They had sold extra bundles of firewood and grass to be able to afford their modest gifts. An emotional Ambedkar recounted to them his own early years, spent in need and misery, promising to do his utmost to uplift the lives of their children. "If I cannot do this, I will take my own life with a gun," he said.

His message to the lower castes, however, was one of unequivocal rebellion among the ranks. Ambedkar urged them to not do the menial tasks they did (and continue to do in some parts of India even decades after him) for a paltry sum. "Stop eating the flesh of dead cattle to quiet the fire in your stomach. Stop cleaning the dirt of the village," he thundered at them. "For so long we have cleared the dirt, now let the one who creates the dirt learn to clean it."

In an essay, writer Mulk Raj Anand remembers Ambedkar telling him about his preference for the Buddhist greeting Om Mani Padmaye ("May the lotuses awake") over namaskar, with its casteist Hindu connotations.

|

| Ambedkar with Savita, 1948 |

Always impeccably dressed in Western attire in stark contrast to other national leaders who usually donned swadeshi clothes, Ambedkar advocated spending half of one's salary on buying books. By the end of his life, he could have made several lakh rupees by selling his collection, but instead, chose to donate the entire holdings to the college he had helped establish in Bombay.

Kartar Singh 'Polonius' recalls being told by Ambedkar about the three books that made him weep — Life of Tolstoy, which he also recommended to his fiancée Sharda Kabir during their courtship as an example of the portrait of an unhappy marriage; Victor Hugo's Les Miserables; and Thomas Hardy's Far From the Madding Crowd. No less was Ambedkar's enthusiasm for newspapers, which he read every day thoroughly and filed away stories from in folders over the decades.

The essay,' Waiting for a Visa' was the closest he came to writing directly about his life, going back to the trials of growing up as a Mahar in rural Maharashtra. In a singularly heartrending episode, Ambedkar describes a journey he undertook with his siblings to meet their father, only to be refused shelter and water by most along the way for their untouchable caste.

|

| Rajagriha, Bombay, February 1934: (L to R) Yashwant, BR Ambedkar, Ramabai, Laxmibai(widow of Ambedkar’s brother, Anandrao), Mukundrao, and dog Toby |

From 1924 to 1934, his library had become one of the biggest in Bombay.

Later, he had a massive collection of more than 50,000 books and he was the most extensive private collection in India.

Babasaheb was a Pet lover, especially a dog lover. He would bring dogs from the farthest corners of the country. He had kept many dogs in Bombay and Delhi.

In his early years, he also had pet deer.

Babasaheb was so close to a dog named Toby that when he died, Babasaheb mourned for days.

He had a great desire to be a painter so that he could paint a portrait of Lord Buddha.

He had an irresistible fascination to possess big and outsized varied types of fountain pens. Among the best were used by him, including Parker, Sheaffer and Waterman.

He also had a golden pen which was given to him by someone from England, which he kept very carefully. His stationary needs were attended by in Bombay: Thacker and Co. John;

In Delhi: Dhoomimal Dass stationary at Connaught Place.

Babasaheb possessed two cars. One in Bombay served him during his early years attending courts as an advocate and legislative assembly sessions. The second one was in Delhi, which was an old mobile model purchased from Rafi Ahmed Kidwai. It was used to attend parliamentary sessions, Ashok Buddha Vihar. The scheduled Castes Federation (SCF) flag always fluttered on the Bonnet.

On July 22, 1942, when Babasaheb took in-charge as Executive Councillor in New Delhi (Labour Ministry), he was searching for a house, there was no place which could accommodate his vast collection of books. After a lot of searching, he selected 22, Prithviraj Marg, New Delhi.

The watchman of the house said that the big house was a haunted house and had remained untenanted even by the English man for several years. The CPWD engineer also discouraged him.

Babasaheb said that “he had been fighting with all sorts of ghosts and spirits in India since his entry into politics. So, let him have his new experience also into this matter”.

The house was thus repaired and all surroundings were replanted. Rows of flowers blossomed all around.

Sometimes, Babasaheb himself used to flower plants at this house.

Ambedkar, B.R. (2019). Pakistan or the Partition of India in Dr Baba Saheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Volume 8, Bombay: Government of Maharashtra

Moon, Vasant. Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, National Book Trust, New Delhi, 1991

Shahare, M.L. and Anil, Nalini, Babasaheb Dr Ambedkar Ki Sangharsh Yatra Evam Sandesh, Samyak Prakashan, New Delhi, 2014

Bahishkrit Bharat mein Prakashit Babasaheb Dr Ambedkar ke Sampadakiye, translation Prabhakar Gajbhiye, Samyak Prakashan, New Delhi, 2017

Keer, Dhananjay, Dr Baba Saheb Ambedkar Jeevan Charit, Popular Prakashan, Mumbai, 2018

Khairmode, Changdeo Bhawanrao, Babasaheb Ambedkar: Jeevan Aur Chintan, Bhaag-1, translation Dr Vimal Kirti, Samyak Prakashan, New Delhi, 2016