His official biodata reads: Graduated in B.A. (Hons.). Born on 18th March 1910. Educated at Laytmer Upper School, Hammersmith and Caius College, Cambridge. Joined the Indian Civil Service on 10.10.1932 and served in Uttar Pradesh as Assistant Magistrate and Collector, Joint Magistrate. Became District and Session Judge on 16.4.1941, appointed Registrar of Allahabad High Court in December 1943, confirmed as District and Sessions Judge on 13th September 1945 and in the Selection Grade on 31.3.1953. Appointed Additional Judge, Allahabad High Court on 8.12.1958. Permanent Judge of Allahabad High Court on 18.2.1959.

Broome came to India as an imperial official in 1932. During a period when British rule in India was still characterised by racial hierarchies and segregation, he defied British prejudices by marrying an Indian woman and devoting his life to India. He even raised his children as Hindus, learned numerous Indian languages and immersed himself in Indian culture.

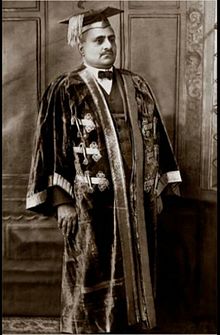

He served in what was then the United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh). In 1937, he married Swaroop Kumari Gour, the daughter of the lawyer, politician and academic Sir Hari Singh Gour. Hari Singh had married Olivia, the daughter of Balwant Singh of Bhandara.

|

| Hari Singh Gour |

When he was 18 years old, Hari Singh Gour went to the University of Cambridge in England where he took Moral Sciences Tripos and Law Tripos. Unfortunately, the young Hari Singh experienced a great deal of racism as a student and throughout his life. He participated in a mathematics competition, of which the results were not declared. Some years after obtaining his LL.D. he learned that the scholarship that the competition awarded was not given to foreigners, especially "blacks," as Indians were referred to by the British. Since Hari Singh came first in the competition, the scholarship ended up not being awarded to anyone. He faced similar treatment in other situations and academic competitions, however, he never let this unfair treatment by the British discourage him. Instead, he began to write poetry. In fact, while in England he came to be known in literary circles as a promising poet, becoming acquainted with the likes of George Bernard Shaw. He wrote a book of poetry entitled Stepping Westward and Other Poems due to which he became somewhat of a celebrity and was thereby selected as a Member of the Royal Society of Literature.

He was admitted as a pensioner at Downing College, Cambridge on 5 June 1889. Gour received his BA in 1892; the MA in 1896; LL.M. in 1902; and finally the LL.D. in 1908. After his time at Cambridge, he read for the D.Litt. and LL.D. at Trinity College, Dublin.

|

| Young Hari Singh Gour |

|

| Gour and Family |

Broome was appointed as a district and sessions judge in 1941. His independence in that role was legendary. When the chief secretary of the United Provinces declared that too many detainees under the Defence of India Rules were receiving bail, Broome responded by threatening the chief secretary with contempt of court.

By 1958, Nehru was able to write of Broome that “I have seldom known any Englishman who has so Indianized himself in various ways as he has”, and that “he is as much as Indian as anybody can be who is not born in India and indeed probably more so than many people born in India”.

In that year, with Nehru’s assistance, Broome renounced his British citizenship and became an Indian citizen.

Unlike other British civil servants, he opted to stay in India as a judge after Independence. He was appointed to the Allahabad High Court, where he served until his retirement in 1972. His judgments in this role demonstrated a strong concern for civil liberties, even going further than the Supreme Court of that time.

One of Broome’s final cases as a judge was to hear the early stages of Raj Narain’s challenge to Indira Gandhi’s 1971 election from Rae Bareli – the challenge that ultimately led to the Emergency. Broome had known Nehru and had once enjoyed a friendly relationship with Indira – he and his wife were even invited to Rajiv and Sonia Gandhi’s wedding reception. But he nonetheless made important procedural rulings in Narain’s favour. (Although Broome’s friendship with Indira Gandhi seems to have ended after this case, it is striking that no effort was made to delegitimise his decisions by referring to his foreign birth.)

1971 was a momentous year in our history. India was celebrating its silver jubilee. The general elections that took place a few months prior to the Bangladesh war had provided a battle cry that sounded as hollow as it was shrill: Garibi Hatao. Yet again, the nation got fooled, perhaps lulled into believing its progenitor – Indira Gandhi. She won a resounding victory.

Raj Narain, her adversary for the keenly contested Lok Sabha seat of Rai Bareli, nearly lost his deposit. But the plucky, bandana-wearing socialist, born in the same year as Indira Gandhi, went to court alleging that Mrs Gandhi had deployed government jeeps during canvassing, thereby violating the code of conduct. The charge of appropriating a few jeeps – 23 to be precise – for the purposes of election canvassing seemed laughable.In the first week of March 1971, Raj Narain and Indira Gandhi crossed swords for the Rai Bareli seat. Mrs Gandhi won handsomely (with a margin of 1,11,810 votes). A month later, on April 24, 1971, Narain filed a petition in the Allahabad High Court challenging Mrs Gandhi’s election on the grounds that she had indulged in corrupt practices. No, not for promoting her kin to positions of limitless power or indulging in shady arms deals, but rather for using official jeeps for canvassing.

Raj Narain alleged that Yashpal Kapur – a gazetted officer who claimed to have retired by the time his expert services were availed of by Mrs Gandhi – had shamelessly distributed quilts, dhotis and alcohol among the voters as an inducement. He had also hired and procured a number of vehicles for the free conveyance of electors to the polling stations.

It was this last allegation that changed the course of India’s history.

On February 24, 1971, Dal Bahadur Singh, President of the District Congress Committee, Rae Bareli, wrote a letter to Yashpal Kapur, in which he commanded Kapur to ask the Electoral Officer to release some jeeps. Dal Bahadur was incensed as this gutsy officer had earlier denied Dal Bahadur’s request on the grounds that “it was not possible to release the vehicles in favour of any party for election purposes”.

Kapur duly obliged but made a grievous error while wording his letter – understandable as he was a gazetted officer. He not only asked the Election Officer to release the 23 vehicles without delay but also stated that the vehicles in question had already been taken by the District Congress Committee.

Tense confusion and truth blurtings aside, this time round the letter had come from none other than the Prime Minister’s election agent, and the poor election officer had no option but to “release” the vehicles that had already been released.

Back then our politicians thought it fit to act on their own advice and not their lawyer’s. Not to be outdone by her electoral agent’s gaffe, Mrs Gandhi gave it in writing to the court that indeed those 23 jeeps had been used by the District Congress Committee Rae Bareli for election purposes in the constituencies of Rae Bareli, Amethi and Ram Sanehi Ghat.

|

| Raj Narain |

Bench: Justice WG Broome

“…After jurisdiction was conferred by the Parliamentary Elections Act, 1868, the court continued to follow the principles, practice and rules on which committees of the House of Commons had previously acted in dealing with election petitions; and as pointed out in Wells v. Wren, (1880) it is admitted that the exhibition of interrogatories to the sitting member by an election committee was a thing unheard of. When elections were introduced in India, however, there was a radical departure from this principle…”

“…The respondent says that the petitioner should not be allowed to supplement these particulars by resorting to discovery. But this argument is misconceived, for discovery has nothing to do with supplementing the petitioner’s pleadings; its object is to elicit admissions from the respondent that may obviate the necessity for producing lengthy evidence when the time comes to examine witnesses.”

“…It is no doubt true that the Indian electoral law has been largely modelled on the corresponding English statutes, but that does not mean that English Common Law doctrines must be followed when interpreting the Indian Law. An objection that an order for discovery of documents might tend to incriminate the party ordered is not sufficient to give immunity from discovery. To sum up, I find that in India there is no warrant for following the English practice of disallowing discovery in the trial of election petitions.”Raj Narain Vs Smt Indira Gandhi & Others

Verdict: Allahabad High Court (http://indiankanoon.org/doc/431532/)

Date: March 20, 1974

Bench: Justice KN Srivastava

It appears Mrs Gandhi was hell-bent on denying Raj Narain and the court a dekko at some documents that included, bizarrely, a “blue book”. The judge wasn’t too pleased with this stand.“In this election petition”, said Justice Srivastava, “privilege has been claimed [by the respondent, ( Mrs Gandhi ) regarding three sets of documents, including copy of a blue book with the title Rules and Instructions for the Protection of Prime Minister when on Tour or in Travel. It shall hereinafter be called as the blue book…The Union Government itself disclosed a part of this blue book, on the top of which the word Secret is printed. The blue book is not an unpublished official record. The State cannot be permitted to have two yardsticks for two different individuals.”

“…Unless the blue book is made available to him, the petitioner cannot be in a position to efficiently cross-examine the respondent’s witnesses. It is, therefore, just, equitable and in accordance with the principle of natural justice that the claim of privilege regarding the blue book and other papers which are correlated with the blue book be rejected.”

|

| Yashpal Kapur with Indira |

|

| Jagmohan Lal Sinha |

The Supreme Court was on vacation. Only one judge was available

Smt. Indira Nehru Gandhi Vs Raj Narain & Another

Verdict: Supreme Court (http://www.indiankanoon.org/doc/1240174/)

Date: June 24, 1975

Bench: Justice VR Krishna Iyer

“While the right to appeal is statutory”, said Justice Iyer, “the power to stay is discretionary. But judicial discretion – indeed, even executive discretion – cannot run riot. Judicial power is dynamic, forward-looking, socially lucent and aware. The Court is the quiet of the storm centre and views with an equal eye the claims on each side. The High Court and its finding, until upset, holds good, however weak it may ultimately prove.”“…I hereby pass a stay of the order of the High Court under appeal. The petitioner will remain a Member of the Lok Sabha, will be entitled to sign the Register kept in the House for that purpose and attend the Sessions of the Lok Sabha, but she will neither participate in the proceedings nor vote nor draw remuneration in her capacity as Member of the Lok Sabha.”

This was anything but the “absolute stay” Mrs Gandhi had wished for. Her anger was palpable. Fascism beckoned her, and at midnight, June 25, 1975, she declared a state of Emergency. We got freedom at midnight and lost it another midnight.

Yashpal Kapur, the one who started it all by providing the jeeps, went on to become, just like his nephew RK Dhawan later on, a member of the Rajya Sabha.

Broome died in Bengaluru in 1988. Having come to India in the service of imperial power, he died an Indian.

Broome’s decision to seek Indian citizenship, and the nation’s willingness to accept his faithful service, highlights interesting aspects of ‘citizenship’ and ‘nationalism’ in the young Indian republic.

He was retained as a judge by the independent Indian government partially through pragmatism: despite the long struggle for independence, free India kept many of the institutions and officials that had governed (even subjugated) colonial India. But his life also reflected important, idealistic aspects of the new Indian state. But the fact that Broome brought up his children as Hindus underlines his belief in the Indian tradition and culture, unlike Nehru.

|

| B N Rau |

He was also closely involved in drafting key provisions of the Government of India Act, of 1935, which later became the template of the Constitution of India. B.N. Rau was also a prolific author and wrote on many aspects of law and jurisprudence.

-----------------------------

Reference: Indira, Jeeps and Blue Books/Anand Ranganathan

Many thanks for this insightful article about my maternal grandfather Justice Broome. From what I know he was one of the few judges who made decisions in favour of India's poor against zamindars. He never accepted their overly generous gifts offered in gratitude. Ashok uncle passed away a few years ago in Pune.

ReplyDelete