Not St Thomas,but St Bartholomew

"In AD 190, the Great Gnostic Pantaenus, a Professor of Theology in the school of Alexandria, set sail from Bernice in the Red Sea and landed after the tedious coasting voyage of those days in one of the Cochin ports, where he found a colony of Christians in possession of the Aramaic version of the Gospel of St. Mathew, in Hebrew, which St. Bartholomew was supposed to have carried thither, and this is the earliest mention of the community now known as the Syrian Christians."

Who was Pantaenus?

Ayyar in his book states:

"In 547 AD, Cosmos, an Alexandrian monk, who was called Indicopleustes on account of his voyages to India, went to Ceylon, and reported that there were churches there. "At Male (Malabar) where pepper grows and at Kalliana Kollam) — Quilon — there is a Bishop who is specially ordained in Persia."

Who was Indicopleustes?

Ayyar states that,"As recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Alfred the Great in 883 sent an embassy to India, headed by Sighelm, bishop of Shireburne, bearing the alms which the King had vowed to send to shrines of St. Thomas and to St Bartholomew in India."

Who was Sighelm?

Ayyar's book refers to The Acta Thomae.What is it?

Who was Sighelm?

Ayyar's book refers to The Acta Thomae.What is it?

Pantaenus was a Stoic philosopher teaching in Alexandria. He was a native of Sicily. He converted to the Christian faith, and sought to reconcile his new faith with Greek philosophy. His most famous student, Clement, who was his successor as head of the Catechetical School, described Pantaenus as "the Sicilian bee". Although no writings by Pantaenus are extant, his legacy is known by the influence of the Catechetical School on the development of Christian theology, in particular in the early debates on the interpretation of the Bible, the Trinity, and Christology. He was the main supporter of Serapion of Antioch for acting against the influence of Gnosticism.

In addition to his work as a teacher, Eusebius of Caesarea reports that Pantaenus was for a time a missionary, travelling as far as India where, according to Eusebius, he found Christian communities using the Gospel of Matthew written in "Hebrew letters", supposedly left them by the Apostle Bartholomew (and which might have been the Gospel of the Hebrews). This may indicate that Syrian Christians, using a Syriac version of the New Testament, had already evangelized parts of India by the late 2nd century. However, some writers have suggested that having difficulty with the language of Saint Thomas Christians, Pantaenus misinterpreted their reference to Mar Thoma (the Aramaic term meaning Saint Thomas), who is currently credited with bringing Christianity to India in the 1st century by the Syrian Churches, as Bar Tolmai (the Hebrew name of Bartholomew). The ancient seaport Muziris on the Malabar Coast (modern day Kerala in India) was frequented by the Egyptians in the early centuries AD.

|

| Ancient trade routes in Silk road map |

Saint Jerome (c. 347 – 30 September 420), apparently relying entirely on Eusebius' evidence from Historia Ecclesiastica, wrote that Pantaenus visited India, “to preach Christ to the Brahmans and philosophers there.”It is unlikely that Jerome has any information about Pantaenus' mission to India that is independent of Eusebius. On the other hand, his claim that "many" of Pantaenus' Biblical commentaries were still extant is probably based on Jerome's own knowledge.

His feast day is July 7.

The Universalist Church of America historian J W Hanson (1899) argued that Pantaenus "must, beyond question" have taught Universalism to Clement of Alexandria and Origen.However, since it is now considered that Clement of Alexandria's views contained a tension between salvation and freewill,and that he and Origen did not clearly teach universal reconciliation of all immortal souls in their understanding of apokatastasis, Hanson's conclusion about Pantaenus lacks a firm basis.

Cosmas Indicopleustes (Cosmas who sailed to India; also known as Cosmas the Monk) was a Greek merchant and later hermit from Alexandria of Egypt.He was a 6th-century traveller, who made several voyages to India during the reign of emperor Justinian. His work Christian Topography contained some of the earliest and most famous world maps.Cosmas was a pupil of the East Syriac Patriarch Aba I and was himself a follower of the Church of the East.

Around 550 Cosmas wrote the once-copiously illustrated Christian Topography, a work partly based on his personal experiences as a merchant on the Red Sea and Indian Ocean in the early 6th century. His description of India and Ceylon during the 6th century is invaluable to historians. Cosmas seems to have personally visited the Kingdom of Axum in modern day northern Ethiopia, as well as Eritrea, India, and Ceylon."Indicopleustes" means "Indian voyager".While it is known from classical literature, especially the Periplus Maris Erythraei, that there had been trade between the Roman Empire and India from the first century BC onwards, Cosmas's report is one of the few from individuals who had actually made the journey. He described and sketched some of what he saw in his Topography. Some of these have been copied into the existing manuscripts, the oldest dating to the 9th century. In 522 AD, he visited the Malabar Coast (South India). He is the first traveller to mention Syrian Christians in present-day Kerala in India. He wrote, "In the Island of Taprobane (Ceylon), there is a church of the Christians, and clerks and faithful. Likewise at Malé where the pepper grows; and in the town of Kalliana, The present Day Kalyan where Comas used to rule, there is also a bishop consecrated in Persia.

A major feature of his Topographia is Cosmas' worldview that the world is flat, and that the heavens form the shape of a box with a curved lid. He was scornful of Ptolemy and others who held that the world was spherical. Cosmas aimed to prove that pre-Christian geographers had been wrong in asserting that the earth was spherical and that it was in fact modelled on the tabernacle, the house of worship described to Moses by God during the Jewish Exodus from Egypt. However, his idea that the earth is flat had been a minority view among educated Western opinion since the 3rd century BC.Cosmas's view was never influential even in religious circles; a near-contemporary Christian, John Philoponus, disagreed with him as did many Christian philosophers of the era.

David C. Lindberg asserts: "Cosmas was not particularly influential in Byzantium, but he is important for us because he has been commonly used to buttress the claim that all (or most) medieval people believed they lived on a flat earth. This claim...is totally false. Cosmas is, in fact, the only medieval European known to have defended a flat earth cosmology, whereas it is safe to assume that all educated Western Europeans (and almost one hundred percent of educated Byzantines), as well as sailors and travelers, believed in the earth's sphericity."

Cosmology aside, Cosmas proves to be an interesting and reliable guide, providing a window into a world that has since disappeared. He happened to be in Adulis on the Red Sea Coast of modern Eritrea at the time (c. 525 AD) when the King of Axum was preparing a military expedition to attack the Jewish king Dhu Nuwas in Yemen, who had recently been persecuting Christians. On request of the Axumite king and in preparation for this campaign, he recorded now-vanished inscriptions such as the Monumentum Adulitanum (which he mistakenly attributed to Ptolemy III Euergetes).

|

| World map by Indicopleustus |

The first member of the subsequent paraphrase of the Saxon Chronicle, by Harris, though unauthorized, is yet necessarily true, as Alfred could not have sent messengers to a shrine, of which he did not know the existence. For the success of the voyage, the safe return, the promotion of Sighelm, and his bequest, the original record gives no authority, although that is the obvious foundation of the story, to which Aserus has no allusion in his life of Alfred. "In the year 883, Alfred, King of England, hearing that there existed a Christian church in the Indies, dedicated to the memory of St Thomas and St Bartholomew, dispatched one Sighelm, or Sithelm, a favourite ecclesiastic of his court, to carry his royal alms to that distant shrine. Sighelm successfully executed the honourable commission with which he had been entrusted, and returned in safety into England. After his return, he was promoted to the bishoprick of Sherburn, or Shireburn, in Dorsetshire; and it is recorded, that he left at his decease, in the treasury of that church, sundry spices and jewels, which he had brought with him from the Indies."

Of this voyage, William of Malmsbury makes twice mention; once in the fourth chapter of his second book, De Gestis Regum Anglorum; and secondly, in the second book of his work; entitled, De Gestis Pontificum Anglorum; and in the chapter devoted to the Bishops of Shireburn, Salisbury, and Winchester, both of which are here added, although the only authority for the story is contained in what has been already given from the Saxon Chronicle42. "King Alfred being addicted to giving of alms, confirmed the privileges which his father had granted to the churches, and sent many gifts beyond seas, to Rome, and to St Thomas in India. His messenger in this business was Sighelm, bishop of Sherburn, who, with great prosperity, which is much to be wondered at in this age, penetrated into India; whence he brought on his return, splendid exotic gems, and aromatic liquors, of which the soil of that region is prolific." "Sighelm having gone beyond seas, charged with alms from the king, even penetrated, with wonderful prosperity, to Saint Thomas in India, a thing much to be admired in this age; and brought thence, on his return, certain foreign kinds of precious stones which abound in that region; some of which are yet to be seen in the monuments of his church."

In the foregoing accounts of the voyage of Sighelm, from the first notice in the Saxon Chronicle, through the additions of Malmsbury, and the amplified paraphrase by Harris, we have an instance of the manner in which ingenious men permit themselves to blend their own imaginations with original record, superadding utterly groundless circumstances, and fancied conceptions, to the plain historical facts.

Thus a motely rhetorical tissue of real incident and downright fable is imposed upon the world, which each successive author continually improves into deeper falsehood. We have here likewise an instance of the way in which ancient manuscripts, first illustrated by commentaries, became interpolated, by successive transcribers adopting those illustrations into the text; and how many fabricators of story, first misled by these additaments, and afterwards misleading the public through a vain desire of producing a morsel of eloquence, although continually quoting original and contemporary authorities, have acquired the undeserved fame of excellent historians, while a multitude of the incidents, which they relate, have no foundations whatever in the truth of record. He only, who has diligently and faithfully laboured through original records, and contemporary writers, honestly endeavouring to compose the authentic history of an interesting period, and has carefully compared, in his progress, the flippant worse than inaccuracies of writers he has been taught to consider as masterly historians, can form an adequate estimate of the enormity and frequency of this tendency to romance. The immediate subject of these observations is slight and trivial; but the evil itself is wide-spread and important, and deserves severe reprehension, as many portions of our national history have been strangely disfigured by such indefensible practices.

The early 3rd-century text called Acts of Thomas is one of the New Testament apocrypha. References to the work by Epiphanius of Salamis show that it was in circulation in the 4th century. The complete versions that survive are Syriac and Greek. There are many surviving fragments of the text. Scholars detect from the Greek that its original was written in Syriac, which places the Acts of Thomas in Edessa. The surviving Syriac manuscripts, however, have been edited to purge them of the most unorthodox overtly Encratite passages, so that the Greek versions reflect the earlier tradition.

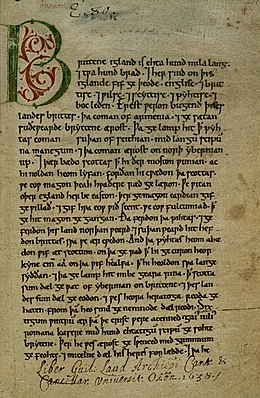

|

| Anglo-Saxon Chronicle |

Fragments of four other cycles of romances around the figure of the apostle Thomas survive, but this is the only complete one. It should not be confused with the early "sayings" Gospel of Thomas. "Like other apocryphal acts combining popular legend and religious propaganda, the work attempts to entertain and instruct. In addition to narratives of Thomas' adventures, its poetic and liturgical elements provide important evidence for early Syrian Christian traditions," according to the Anchor Bible Dictionary.

Acts of Thomas is a series of episodic Acts (Latin passio) that occurred during the evangelistic mission of Judas Thomas ("Judas the Twin") to India. It ends with his martyrdom: he dies pierced with spears, having earned the ire of the monarch Misdaeus because of his conversion of Misdaeus' wives and a relative, Charisius. He was imprisoned while converting Indian followers won through the performing of miracles.

Embedded in the Acts of Thomas at different places according to differing manuscript traditions is a Syriac hymn, The Hymn of the Pearl, (or Hymn of the Soul), a poem that gained a great deal of popularity in mainstream Christian circles. The Hymn is older than the Acts into which it has been inserted, and is worth appreciating on its own. The text is interrupted with the poetry of another hymn, the one that begins "Come, thou holy name of the Christ that is above every name" (2.27), a theme that was taken up in Catholic Christianity in the 13th century as the Holy Name.

Mainstream Christian tradition rejects the Acts of Thomas as pseudepigraphical and apocryphal, and for its part, the Roman Catholic Church declared Acts as heretical at the Council of Trent.

Thomas is often referred to by his name Judas (his full name is Thomas Judas Didymus), since both Thomas and Didymus just mean twin, and several scholars believe that twin is just a description, and not intended as a name. The manuscripts end "The acts of Judas Thomas the apostle are completed, which he did in India, fulfilling the commandment of him that sent him. Unto whom be glory, world without end. Amen.".

The Acts of Thomas connects Thomas, the apostle's Indian ministry with two kings, According to one of the legends in the Acts, Thomas was at first reluctant to accept this mission, but the Lord appeared to him in a night vision and said, “Fear not, Thomas. Go away to India and proclaim the Word, for my grace shall be with you.” But the Apostle still demurred, so the Lord overruled the stubborn disciple by ordering circumstances so compelling that he was forced to accompany an Indian merchant, Abbanes, to his native place in north-west India, where he found himself in the service of the Indo-Parthian king Gondophares. The apostle's ministry resulted in many conversions throughout the kingdom, including the king and his brother.

According to the legend, Thomas was a skilled carpenter and was bidden to build a palace for the king. However, the Apostle decided to teach the king a lesson by devoting the royal grant to acts of charity and thereby laying up treasure for the heavenly abode. But at least by the year of the establishment of the Second Persian Empire (226), there were bishops of the Church of the East in north-west India comprising Afghanistan and Baluchistan, with laymen and clergy alike engaging in missionary activity.

The Acts of Thomas identifies his second mission in India with a kingdom ruled by King Mahadeva, one of the rulers of a 1st-century dynasty in southern India. It is most significant that, aside from a small remnant of the Church of the East in Kurdistan, the only other church to maintain a distinctive identity is the Mar Thoma or “Church of Thomas” congregations along the Malabar Coast of Kerala State in southwest India. According to the most ancient tradition of this church, Thomas evangelized this area and then crossed to the Coromandel Coast of southeast India, where, after carrying out a second mission, he died in Mylapore near Madras. Throughout the period under review, the church in India was under the jurisdiction of Edessa, which was then under the Mesopotamian patriarchate at Seleucia-Ctesiphon and later at Baghdad and Mosul. Historian Vincent A. Smith says, “It must be admitted that a personal visit of the Apostle Thomas to South India was easily feasible in the traditional belief that he came by way of Socotra, where an ancient Christian settlement undoubtedly existed. I am now satisfied that the Christian church of South India is extremely ancient... ”.

Although there was a lively trade between the Near East and India via Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf, the most direct route to India in the 1st century was via Alexandria and the Red Sea, taking advantage of the Monsoon winds, which could carry ships directly to and from the Malabar coast. The discovery of large hoards of Roman coins of 1st-century Caesars and the remains of Roman trading posts testify to the frequency of that trade. In addition, thriving Jewish colonies were to be found at the various trading centers, thereby furnishing obvious bases for the apostolic witness.

Piecing together the various traditions, one may conclude that Thomas left north-west India when invasion threatened and traveled by vessel to the Malabar coast, possibly visiting southeast Arabia and Socotra en route and landing at the former flourishing port of Muziris on an island near Cochin (c. AD 51–52). From there he is said to have preached the gospel throughout the Malabar coast, though the various churches he founded were located mainly on the Periyar River and its tributaries and along the coast, where there were Jewish colonies.He reputedly preached to all classes of people and had about seventeen thousand converts, including members of the four principal castes. Later, stone crosses were erected at the places where churches were founded, and they became pilgrimage centres. In accordance with apostolic custom, Thomas ordained teachers and leaders or elders, who were reported to be the earliest ministry of the Malabar church.

Acts of Thomas is a series of episodic Acts (Latin passio) that occurred during the evangelistic mission of Judas Thomas ("Judas the Twin") to India. It ends with his martyrdom: he dies pierced with spears, having earned the ire of the monarch Misdaeus because of his conversion of Misdaeus' wives and a relative, Charisius. He was imprisoned while converting Indian followers won through the performing of miracles.

Embedded in the Acts of Thomas at different places according to differing manuscript traditions is a Syriac hymn, The Hymn of the Pearl, (or Hymn of the Soul), a poem that gained a great deal of popularity in mainstream Christian circles. The Hymn is older than the Acts into which it has been inserted, and is worth appreciating on its own. The text is interrupted with the poetry of another hymn, the one that begins "Come, thou holy name of the Christ that is above every name" (2.27), a theme that was taken up in Catholic Christianity in the 13th century as the Holy Name.

Mainstream Christian tradition rejects the Acts of Thomas as pseudepigraphical and apocryphal, and for its part, the Roman Catholic Church declared Acts as heretical at the Council of Trent.

Thomas is often referred to by his name Judas (his full name is Thomas Judas Didymus), since both Thomas and Didymus just mean twin, and several scholars believe that twin is just a description, and not intended as a name. The manuscripts end "The acts of Judas Thomas the apostle are completed, which he did in India, fulfilling the commandment of him that sent him. Unto whom be glory, world without end. Amen.".

|

| First page of the Gospel of Judas |

The Acts of Thomas connects Thomas, the apostle's Indian ministry with two kings, According to one of the legends in the Acts, Thomas was at first reluctant to accept this mission, but the Lord appeared to him in a night vision and said, “Fear not, Thomas. Go away to India and proclaim the Word, for my grace shall be with you.” But the Apostle still demurred, so the Lord overruled the stubborn disciple by ordering circumstances so compelling that he was forced to accompany an Indian merchant, Abbanes, to his native place in north-west India, where he found himself in the service of the Indo-Parthian king Gondophares. The apostle's ministry resulted in many conversions throughout the kingdom, including the king and his brother.

According to the legend, Thomas was a skilled carpenter and was bidden to build a palace for the king. However, the Apostle decided to teach the king a lesson by devoting the royal grant to acts of charity and thereby laying up treasure for the heavenly abode. But at least by the year of the establishment of the Second Persian Empire (226), there were bishops of the Church of the East in north-west India comprising Afghanistan and Baluchistan, with laymen and clergy alike engaging in missionary activity.

The Acts of Thomas identifies his second mission in India with a kingdom ruled by King Mahadeva, one of the rulers of a 1st-century dynasty in southern India. It is most significant that, aside from a small remnant of the Church of the East in Kurdistan, the only other church to maintain a distinctive identity is the Mar Thoma or “Church of Thomas” congregations along the Malabar Coast of Kerala State in southwest India. According to the most ancient tradition of this church, Thomas evangelized this area and then crossed to the Coromandel Coast of southeast India, where, after carrying out a second mission, he died in Mylapore near Madras. Throughout the period under review, the church in India was under the jurisdiction of Edessa, which was then under the Mesopotamian patriarchate at Seleucia-Ctesiphon and later at Baghdad and Mosul. Historian Vincent A. Smith says, “It must be admitted that a personal visit of the Apostle Thomas to South India was easily feasible in the traditional belief that he came by way of Socotra, where an ancient Christian settlement undoubtedly existed. I am now satisfied that the Christian church of South India is extremely ancient... ”.

Although there was a lively trade between the Near East and India via Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf, the most direct route to India in the 1st century was via Alexandria and the Red Sea, taking advantage of the Monsoon winds, which could carry ships directly to and from the Malabar coast. The discovery of large hoards of Roman coins of 1st-century Caesars and the remains of Roman trading posts testify to the frequency of that trade. In addition, thriving Jewish colonies were to be found at the various trading centers, thereby furnishing obvious bases for the apostolic witness.

Piecing together the various traditions, one may conclude that Thomas left north-west India when invasion threatened and traveled by vessel to the Malabar coast, possibly visiting southeast Arabia and Socotra en route and landing at the former flourishing port of Muziris on an island near Cochin (c. AD 51–52). From there he is said to have preached the gospel throughout the Malabar coast, though the various churches he founded were located mainly on the Periyar River and its tributaries and along the coast, where there were Jewish colonies.He reputedly preached to all classes of people and had about seventeen thousand converts, including members of the four principal castes. Later, stone crosses were erected at the places where churches were founded, and they became pilgrimage centres. In accordance with apostolic custom, Thomas ordained teachers and leaders or elders, who were reported to be the earliest ministry of the Malabar church.

|

| Image of St Thomas |

The text is broken by headings:

- 1 - when he went into India with Abbanes the merchant. The apostles cast lots to see who will go where as a missionary. Thomas gets India, but refuses his mission, even after Jesus speaks to him. Jesus then appears in human form and sells Thomas to a merchant as a slave, since Thomas is skilled as a carpenter. Thomas is then asked if Jesus is his master, which he affirms. It is only then he accepts his mission.

- 2 - concerning his coming unto the king Gundaphorus

- 3 - concerning the servant

- 4 - concerning the colt

- 5 - concerning the devil that took up his abode in the woman

- 6 - of the youth that murdered the Woman. A young couple begin to have relationship problems when the woman proves to be too keen on sex, while the male advocates being chaste, honouring the teachings of Thomas. So the male kills his lover. He comes to take the eucharist with others in the presence of Thomas, but his hand withers, and Thomas realises that the male has committed a crime. After being challenged, the male reveals his crime, and the reason for it, so Thomas forgives him, since his motive was good, and goes to find the woman's body. In an inn, Thomas and those with him lay the woman's body on a couch, and, after praying, Thomas has the male hold the woman's hand, whereupon the woman comes back to life.

- The story clearly has the gnostic themes of death and resurrection, death not being a bad thing but a result of the pursuit of gnostic teaching, and the resurrection into greater life (and they lived happily ever after) once gnostic teaching is understood.

- 7 - of the Captain

- 8 - of the wild asses

- 9 - of the Wife of Charisius

- 10 - wherein Mygdonia receiveth baptism

- 11 - concerning the wife of Misdaeus

- 12 - concerning Ouazanes (Iuzanes) the son of Misdaeus

- 13 - wherein Iuzanes receiveth baptism with the rest

- The Martyrdom of Thomas

- Leucius Charinus

|

| St John with Bartholomew( right) /Dosso Dossi,1527 |

It is clear now that St Barthalomew was in India and maybe,Kerala.

Eusebius of Caesarea Ecclesiastical History (5:10) states that after the Ascension, Bartholomew went on a missionary tour to India, where he left behind a copy of the Gospel of Matthew. Other traditions record him as serving as a missionary in Ethiopia, Mesopotamia, Parthia, and Lycaonia.Popular traditions and legends say that Bartholomew preached the Gospel in India, then went to Greater Armenia.

Since it has been accepted that St Thomas was never in India,it is better to replace him with Bartholomew.

© Ramachandran