The Canon Laws were Frozen Later

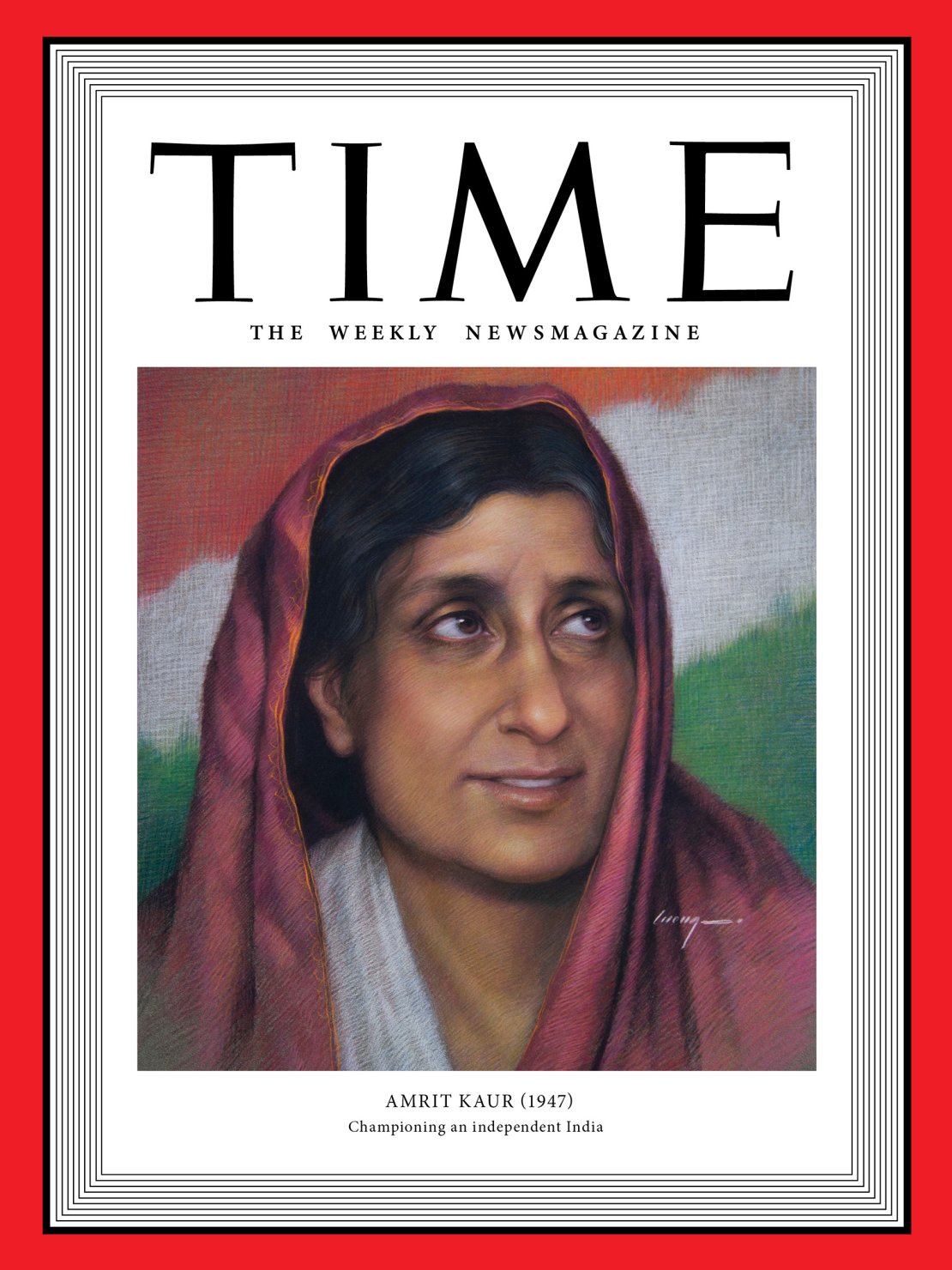

The Diamper Synod of 1599,convened by the Portuguese Goa Arch Bishop Alexio de Menezes,seems to me a mimicry of the Council of Trent held during 1545-1563.Like the Council of Trent called by three Popes,the Diamper Synod is characterised by sweeping decrees,aimed at imposition of the Pope's supremacy over the Indian Church.It was vehemently challenged by the Koonan Cross Oath of 1653 and the Diamper decrees were frozen.There is a tendency in the Latin Church in Kerala to glorify the Synod as as a creative dialogue between two versions of the faith-the Eurocentric and Indian.Ultimately indianness prevailed.

Certain canons the Synod passed are termed as progressive by the Latin Church,like the clause for the share of property even to the women.But it is known to everyone the Supreme Court had to intervene finally in 1986 in the Mary Roy case to establish the right of Christian women in the Father's wealth.

Diamper is the Portuguese name for Udayamperur,near Tripunithura in Cochin.A stone's throw away from,my home.

Synod of Diamper

It was the council that formally united the ancient Thomas Christians of the Malabar Coast of Southwestern India with the Roman Catholic Church. It was convoked in 1599 by Aleixo de Meneses, archbishop of Goa. The Synod renounced Nestorianism, the heresy that believed in two persons rather than two natures in Christ, as the Indians were suspected of being heretics by the Portuguese missionaries. The local patriarch—representing the Assyrian Church of the East, to which ancient Christians in India had looked for ecclesiastical authority—was then removed from jurisdiction in India and replaced by a Portuguese bishop; the East Syrian liturgy of Addai and Mari was “purified from error”; and Latin vestments, rituals, and customs were introduced to replace the ancient traditions. The forced Latinization and disregard for local tradition were accompanied by violence and led to schism among Thomas Christians by the mid-17th century.

As the Thomas Christian community grew, its members enjoyed about a millennium of theological and ecclesiastical cohesion and unity. That state of affairs changed after the Portuguese arrival. In April 1498 two Thomas Christians piloted Vasco da Gama’s small fleet from Melinda (East Africa) to Calicut (present-day Kozhikode), an event recorded by two Thomas Christian metrans (Malayam for “bishop”). Half a century later two more Thomas Christians made it possible for the Jesuit missionary St. Francis Xavier to bring shoreline fisherfolk, the Parayars and Mukkavars, into the Roman Catholic fold. Nevertheless, harmonious relations with the Catholics did not last. After 1561, Thomas Christians were branded heretics by the Goa Inquisition, which had been established under Portuguese rule. The 1599 Synod of Diamper anathematized the catholicos of Chaldea and all Christians of India who did not submit to Rome. Ancient churches were destroyed, libraries were burned, and clerics from Mesopotamia were intercepted, imprisoned, and executed.

Yet, eventually, ancient skills of silent resistance and subversion wore out one prelate after another. In 1653 anti-Catholic kattanars met at Koonen (“Crooked”) Cross, a granite monument at Mattancheri. There they swore an oath to never again accept another farangi (European) prelate and installed their own high metran (patriarch). Archdeacon (Ramban) Parambil Thoma became their first indigenous prelate, taking the title Mar Thoma I (Mar is a Syriac term meaning “Saint”). A schism occurred, with some Thomas Christian clergy remaining Roman Catholic while others divided between East Syrian (more closely affiliated with the Assyrian Church of the East) and West Syrian (called Jacoba, after the evangelist Jacob Baradaeus) authority. The unity that Thomas Christians had enjoyed for a thousand years ended in the proliferation of ever more denominations.

Dutch ascendancy along the Malabar Coast in the 17th century helped Thomas Christian communities preserve their ecclesiastical autonomy. The Portuguese Estado da India (“State of India”) could no longer enforce its writ outside Goa. Portuguese control over Thomas Christian Catholics was challenged by Roman Catholic missionaries sent by the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith. The schism lasted until the 19th century, when the Synod of Pondicherry (present-day Puducherry), organized by Msgr. Clement Bonnand, eventually led to a Latin-rite Catholic hierarchy. Non-Catholic Syrian Thomas Christian communities survived but continued to struggle for autonomy.

|

| Council of Trent 1545/By Nicolo Dorigati |

As the English East India Company gained ascendancy in the 18th century, Thomas Christians faced new challenges. In 1806 High Metran Mar Dionysius I (Mar Thoma VI) presented an ancient (perhaps 12th-century) copy of Syriac scriptures to Claudius Buchanan, a Church of England clergyman and representative of the government of India. In return, Mar Dionysius I was promised a missionary teacher, a modern seminary for training Thomas Christian clergy, and a Malayalam translation of scriptures for every pulpit. The partnership was ended by the Synod of Mavelikkara in 1836, when Thomas Christians broke away from Anglican domination. Reform-minded Thomas Christians at Kottayam Seminary then broke away from the high metran’s authority. A splinter group became Anglican, while most reformers staunchly adhered to ancient church traditions. Among Thomas Christian Catholics, meanwhile, struggles over Syrian, Latin, and Malabar rites continued. European Catholic prelates tried to bring autonomous Thomas Christian churches under the authority of Rome.

Council of Trent

It was the 19th ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church, held in three parts from 1545 to 1563. Prompted by the Reformation, the Council of Trent was highly important for its sweeping decrees on self-reform and for its dogmatic definitions that clarified virtually every doctrine contested by the Protestants. Despite internal strife and two lengthy interruptions, the council was a key part of the Counter-Reformation and played a vital role in revitalizing the Roman Catholic Church in many parts of Europe.

Period I: 1545–47

Though Germany demanded a general council following the excommunication of the German Reformation leader Martin Luther, Pope Clement VII held back for fear of renewed attacks on his supremacy. France, too, preferred inaction, afraid of increasing German power. Clement’s successor, Paul III, however, was convinced that Christian unity and effective church reform could come only through a council. After his first attempts were frustrated, he convoked a council at Trent (northern Italy), which opened on December 13, 1545.As the council opened, some bishops urged for immediate reform, and others sought clarification of Catholic doctrines; a compromise was reached whereby both topics were to be treated simultaneously. The council then laid the groundwork for future declarations: the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed was accepted as the basis of Catholic faith; the canon of Old and New Testament books was definitely fixed; tradition was accepted as a source of faith; the Latin Vulgate was declared adequate for doctrinal proofs; the number of sacraments was fixed at seven; and the nature and consequences of original sin were defined. After months of intense debate, the council ruled against Luther’s doctrine of justification by faith alone: man, the council said, was inwardly justified by cooperating with divine grace that God bestows gratuitously. By enjoining on bishops an obligation to reside in their respective sees, the church effectively abolished plurality of bishoprics. Political problems forced the council’s transfer to Bologna and finally interrupted its unfinished work altogether.

Period II: 1551–52

Before military events forced a second adjournment of the council, the delegates finished an important decree on the Eucharist that defined the Real Presence of Christ in opposition to the interpretation of Huldrych Zwingli, the Swiss Reformation leader, and the doctrine of transubstantiation as opposed to that of Luther’s consubstantiation. The sacrament of penance was extensively defined, extreme unction (later, the anointing of the sick) explained, and decrees issued on episcopal jurisdiction and clerical discipline. German Protestants, meanwhile, were demanding a reconsideration of all the council’s previous doctrinal decrees and wanted a statement asserting that a council’s authority is superior to that of the pope.

Period III: 1562–63

Pope Paul IV (1555–59) was opposed to the council, but it was reinstated by Pius IV (1559–65). The arrival of French bishops reopened the explosive question regarding the divine basis for the obligations of bishops to reside in their sees. When peace was restored, the council defined that Christ is entirely present in both the consecrated bread and the consecrated wine in the Eucharist but left to the pope the practical decision of whether or not the chalice should be granted to the laity. It defined the mass as a true sacrifice; issued doctrinal statements on holy orders, matrimony, purgatory, indulgences, and the veneration of saints, images, and relics; and enacted reform decrees on clerical morals and the establishment of seminaries.

Pius IV confirmed the council’s decrees in 1564 and published a summary of its doctrinal statements; observance of disciplinary decrees was imposed under sanctions. In short order the catechism of Trent appeared, the missal and breviary were revised, and eventually a revised version of the Bible was published. By the end of the century, many of the abuses that had motivated the Protestant Reformation had disappeared, and the Roman Catholic Church had reclaimed many of its followers in Europe. The council, however, failed to heal the schism that had sundered the Western Christian church.

The Canon Law

From the time that the Gregorian Reform introduced a more centralized ecclesiastical administration, the number of appeals to Rome and the number of papal decisions mounted. New papal laws and decisions, called decretals, first added to Gratian’s Decretum, were soon gathered into separate collections, of which the best known are the Quinque compilationes antiquae (“Five Ancient Compilations”). The first, the Breviarium extravagantium (“Compendium of Decretals Circulating Outside”; i.e., not yet collected) of Bernard of Pavia, introduced a system inspired by the codification of Justinian, a division of the material into five books, briefly summarized in the phrase judex, judicium, clerus, connubium, crimen (“judge, trial, clergy, marriage, crime”). Each book was subdivided into titles and these in turn into capitula, or canons. This system was taken over by all subsequent collections of decretals. These compilations were the foremost source of the Liber extra (“Book Outside”—i.e., of decretals not in Gratian’s Decretum), or Liber decretalium Gregorii IX (“Book of Decretals of Gregory IX”), composed by St. Raymond of Peñafort, a Spanish canonist, and promulgated on September 5, 1234, as the exclusive codex for all of canon law after Gratian. On March 3, 1298, Pope Boniface VIII promulgated Liber sextus (“Book Six”), composed of official collections of Innocent IV, Gregory X, and Nicholas III and private collections and decretals of his own, as the exclusive codex for the canon law since the Liber extra. The Constitutiones Clementinae (“Constitutions of Clement”) of Pope Clement V, most of which were enacted at the Council of Vienne (1311–12), were promulgated on October 25, 1317, by Pope John XXII, but they were not an exclusive collection. The Decretum Gratiani, the Liber extra, Liber sextus, and the Constitutiones Clementinae, with the addition of two private collections, the Extravagantes of John XXII and the Extravagantes communes (“Decretals Commonly Circulating”), were printed and published together for the first time in Paris in 1500. This entire collection soon received the name Corpus Juris Canonici (“Corpus of Canon Law”).

The science of canon law was developed by the writers of glosses, the commentators on the Decree of Gratian (decretists), and the commentators on the collections of decretals (decretalists). Their glosses were based on the system used by Gratian: next to the texts of canons parallel texts were noted, then conflicting ones, followed by a solutio (“solution”), again with text references. In connection with this the glosses of other canonists were also introduced. In this way the apparatus glossarum, continuous commentaries on the entire book, arose. The glossa ordinaria (“ordinary explanation”) on the different parts of the Corpus Juris Canonici was the apparatus that was used universally in the schools. After the classical period of the glossators (12th–14th century), terminated by the work of a lay Italian canonist, John Andreae (c. 1348), came that of the post-glossators. In the absence of new legislation in the time of the “Babylonian Captivity” (1309–77), when the papacy was situated at Avignon, France, and the Western Schism (1378–1417), when there were at least two popes reigning simultaneously, the commentaries on decretals continued but with a larger production of special tracts—e.g., regarding the laws of benefices and marriage and of consilia (advice about concrete legal questions).

Toward the end of the Middle Ages, decretal law ceased to govern. Medieval Christian society became politically and ecclesiastically divided according to the principle of cujus regio, ejus religio (“whose region, his religion”; i.e., the religion of the prince is the religion of the land). In Protestant areas the former Roman Catholic church buildings and benefices were taken over by other churches; and even in the lands that remained Roman Catholic the churches found themselves in an isolated position as secularization forced them to reorganize. With the end of feudalism, canon law dealing with benefices, chapters, and monasteries, which were closely bound to the feudal structure, changed. The territorial, material, and economic character of canon law and the decentralization allied with it disappeared. The decision of the reform councils from Pisa (1409) until the fifth Lateran Council (1512–17) affected, in particular, benefices, papal reservations, taxes, and other such ecclesiastical matters. In the same period various concordats (agreements) permitted the princes to intervene in the issue of ecclesiastical benefices and property. Canon law took on a more defensive character, with prohibitions regarding books, mixed marriages, participation of Roman Catholics in Protestant worship and vice versa, education of the clergy in seminaries, and other such areas of concern.

At the Roman Catholic reform Council of Trent (1545–63), a new foundation for the further development of canon law was expressed in the Capita de reformatione (“Articles Concerning Reform”), which were discussed and accepted in 10 of the 25 sessions. Papal primacy was not only dogmatically affirmed against conciliarism (the view that councils are more authoritative than the pope) but was also juridically strengthened in the conduct and implementation of the council. The central position of the bishops was recovered, over against the decentralization that had been brought about by the privileges and exemptions of chapters, monasteries, fraternities, and other corporate bodies that sprang from Germanic law, as well as caused by the rights granted to patrons. In practically all matters of reform the bishops received authority ad instar legati S. Sedis (“like delegates of the Holy See”). Strict demands were made for admission to ordination and offices; measures were taken against luxurious living, nepotism, and the neglect of the residence obligation; training of the clergy in seminaries was prescribed; prescriptions were given about pastoral care, schools for the young, diocesan and provincial synods, confession, and marriage; the right to benefices was purified of misuse; and the formalistic law of procedure was simplified.

The council gave the duty of execution of the reform to the Pope. On January 26, 1564, Pius IV confirmed the decisions and reserved for himself their interpretation and execution, and on August 2, 1564, he established the Congregation of the Council for that purpose. The congregations of cardinals, which proceeded from the former permanent commissions of the consistorium (the assembly of the pope with the Sacred College of Cardinals), were organized by Pope Sixtus V in 1587. Since then the administrative apparatus of the Roman Curia has consisted of congregations of cardinals together with courts and offices. This apparatus made it possible for the Latin church to acquire a uniform canon law system that was developed in detail.

|

| First Vatican Council,1859 |

Expansion of the church brought with it expansion of the ordinary hierarchical episcopal structure. This was true also for the new colonies under the right of patronage of the Spanish and Portuguese kings. In the other mission areas and in the areas taken over by the Protestants, where the realization of the episcopal structure and the decretal law adopted by Trent was not possible, the organization of mission activity was taken from missionaries and religious orders and given to the Holy See. The Sacred Congregation for Propagation of the Faith (the Propaganda) was established for this purpose in 1622. Missionaries received their mandate from Rome; the administration was given over to apostolic vicars (bishops of territories having no ordinary hierarchy) and prefects (having episcopal powers, but not necessarily bishops) who were directly dependent on the Propaganda, from which they received precisely described faculties. A new, uniform mission law was created, without noteworthy native influence; this sometimes led to conflict, such as the Chinese rites controversy in the 17th and 18th centuries over the compatibility of rites honouring Confucius and ancestors with Christian rites.

The First Vatican Council (1869–70) strengthened the central position of the papacy in the constitutional law of the church by means of its dogmatic definition of papal primacy. Disciplinary canons were not enacted at the council, but the desire expressed by many bishops that canon law be codified did have influence on the emergence and content of the code of canon law.

Since the closing off of the Corpus Juris Canonici, there had been no official or noteworthy private collection of the canon law except for the constitutions of Pope Benedict XIV (reigned 1740–58). The material was spread out in the collections of the Corpus Juris Canonici and in the generally very incomplete private publications of the acta of popes, of general and local councils, and the various Roman congregations and legal organs, which made canon law into something unmanageable and uncertain. The need for codification was recognized even more because of the fact that since the end of the 18th century, secular law had undergone a period of great codification. Several private attempts to do this had met with little success.

On March 19, 1904, Pius X announced his intention to complete the codification, and he named a commission of 16 cardinals, with himself as chairman. Bishops and university faculties were asked to cooperate. The schemata of the five books that were prepared in Rome—universal norms, personal law, law of things, penal law, and procedural law—were proposed in the years 1912–14 to all those who would ordinarily be summoned to an ecumenical council, and with their observations were then reworked in the cardinals’ commission. The entire undertaking and all the drafts were under the papal seal of secrecy and were not published. Meanwhile, Pius X introduced various reforms that were to a great degree the results of the commission’s work. In July 1916 the preparations for the Codex Juris Canonici (“Code of Canon Law”) were completed. The code was promulgated on Pentecost Sunday, May 27, 1917, and became effective on Pentecost Sunday, May 19, 1918.

In contrast to all earlier official collections, this code was a complete and exclusive codification of all universal church law then binding in the Latin church. Out of fear of political difficulties, a systematic handling of public church law, especially what concerned the relations between church and state, was omitted. Its main purpose was to offer a codification of the law, and only incidentally adaptation, and so it introduced relatively little that was new legislation. The 2,414 canons were divided into five books that no longer followed the system of the collections of decretals but did follow that of the Perugian canonist Paul Lancelotti’s Institutiones juris canonici (1563; “Institutions of Canon Law”), which in turn went back to the division of the 2nd-century Roman lawyer Gaius’s Institutiones—one section on persons, two sections on things, and one section on actions—and was based on the fundamental idea of Roman law—i.e., subjective right. In some editions the sources that were used by the editors were indicated at the individual canons. With the publication of the codex these sources belonged to the history of the law. Older general and particular law, in conflict with the codex, was given up and, insofar as it was not in conflict with it, served only as a means for interpreting the code. The old law of custom in conflict with the code and expressly reprobated by it was rendered null; when not reprobated and 100 years old or immemorial, it could be allowed by ordinaries for pressing reasons. Acquired rights and concordats in force remained in force. With this change, an independent science of the history of canon law became necessary, in addition to the dogmatic canonical science of canon law on the basis of the code.

|

| Our Lady of Life Church,Mattancherry,Venue of Coonan Cross Oath |

In order to ensure the unity of the codification and the law, a commission of cardinals was established on September 15, 1917, for the authentic interpretation of the new code. At the same time it was decided that the cardinals’ congregations should no longer make new general decrees but only instructions for the carrying out of the prescriptions of the code. Should a general decree appear necessary, it was determined, the commission would formulate new canons and insert them into the code. Neither of these decisions was carried out. Only two canons were altered and congregations promulgated numerous general decrees. New papal legislation complemented and altered the law of the code.

Catholic Eastern churches (churches in union with the Roman Catholic Church) retain their own traditions in liturgy and church order, insofar as these are not considered to be in conflict with the norms taken by Rome to be divine law. In 1929 Pius XI set up a commission of cardinals for the codification of canon law valid for all Uniate churches in the East. In the following year a commission was established for the preparation of the codification and another for the collection of the sources of Eastern law, in which experts of all rites were involved. These collections were published in three series, begun respectively in 1930, 1935, and 1942.

In 1935 the preparatory commission became the Pontifical Commission for the Redaction of the Codex Juris Canonici Orientalis (“Code of Oriental Canon Law”). The cooperation of all Eastern ordinaries (bishops, patriarchs, and others having jurisdictions) was requested, and the drafts of the various documents were sent to them. Thereafter four parts were published: in 1949, on marriage law; in 1952, on the law for monks and other religious, on ecclesiastical properties, and a title De Verborum Significatione (“Concerning the Meaning of Words,” a series of definitions of legal terms used in the canons); and in 1957, on constitutional law, especially of the clergy. The still-incomplete codification followed the Latin code with the assimilation of the authentic interpretation and with textual corrections, as well as with the insertion of the general law proper to the Eastern churches, including the Orthodox churches, regarding the patriarchs and their synods, marriage law, the law of religious, and other matters. The promulgation was made only in Latin in the Acta Apostolicae Sedis, the official organ of the Holy See. The Catholic Eastern churches came under the Congregation for the Eastern Churches that was established on January 6, 1862, by Pius IX as part of the Propaganda Fide; it was made independent by Benedict XV on May 1, 1917, and expanded considerably by Pius XI on March 25, 1938. Roman legislation as well as the jurisdiction of a congregation of the Roman Curia was criticized as being incompatible with the traditional autonomy of the Eastern churches in legislation and administration.

© Ramachandran