The Swapna Suresh case in Kerala,reminds one of the Olga case in which over 40 officers of the Customs were booked for aiding smuggling in exchange for sexual favours and bribes.

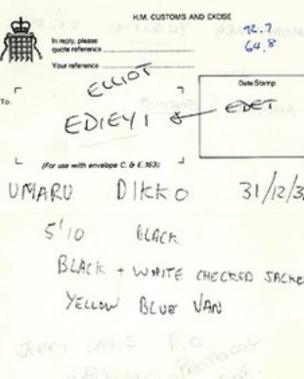

On 28 August 2000, Olga Kozireva, an Uzbek, arrived at Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport from Bishkek by Kyrgyzstan Airlines flight No K2-545.The arrival of a woman from a former Soviet republic was not a rarity, but, Olga stood out. She was 26, fluent in Russian with a little English to get by, and she had a diploma in medicine from the Red Cross Society in Tashkent. Her grainy passport photograph suggested a look that was to become famous a decade later with the release of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. And her effrontery at the airport actually seemed to belong in fiction. She had the temerity to walk through the green channel with 27 bags weighing a total of 2,200 kg ( it weighed more than 4000 kg) registered on her air ticket.

In that year alone, between January and August, she had travelled to India 68 times, often with even bigger consignments. But something finally went wrong that day. After four years of letting Olga and several other Uzbek women walk past with little or no scrutiny, a Customs officer decided to act.He was Y Rama Murthy,who caught the 30 kg gold in the UAE diplomatic baggage,in Kerala,later.

Since 1997, Olga and her accomplices had been brazenly walking through the airport’s green channel—for those with nothing to declare—with tonnes of baggage. The day she was caught, the consignment had Chinese silk being flown in from Uzbekistan, a prohibited item that had done great damage to India’s domestic industry. In 2000 alone, there were 23 instances of similar consignments of Chinese silk being cleared with only nominal penalties. Officials on duty, had deliberately noted only small quantities of Chinese silk in their records, charged minor penalties and let huge consignments into the country.

On 28 August 2000, Olga Kozireva, an Uzbek, arrived at Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport from Bishkek by Kyrgyzstan Airlines flight No K2-545.The arrival of a woman from a former Soviet republic was not a rarity, but, Olga stood out. She was 26, fluent in Russian with a little English to get by, and she had a diploma in medicine from the Red Cross Society in Tashkent. Her grainy passport photograph suggested a look that was to become famous a decade later with the release of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. And her effrontery at the airport actually seemed to belong in fiction. She had the temerity to walk through the green channel with 27 bags weighing a total of 2,200 kg ( it weighed more than 4000 kg) registered on her air ticket.

In that year alone, between January and August, she had travelled to India 68 times, often with even bigger consignments. But something finally went wrong that day. After four years of letting Olga and several other Uzbek women walk past with little or no scrutiny, a Customs officer decided to act.He was Y Rama Murthy,who caught the 30 kg gold in the UAE diplomatic baggage,in Kerala,later.

Since 1997, Olga and her accomplices had been brazenly walking through the airport’s green channel—for those with nothing to declare—with tonnes of baggage. The day she was caught, the consignment had Chinese silk being flown in from Uzbekistan, a prohibited item that had done great damage to India’s domestic industry. In 2000 alone, there were 23 instances of similar consignments of Chinese silk being cleared with only nominal penalties. Officials on duty, had deliberately noted only small quantities of Chinese silk in their records, charged minor penalties and let huge consignments into the country.

|

An official involved revealed to Customs investigators that apart from the Uzbek women provided to them for sex, a bribe of roughly $500 was paid on every bag brought in.

On the day she was caught, Olga had 27 bags, and an estimated Rs 5 lakh had been arranged as a bribe to evade Customs duty of around Rs 50 lakh. Taking into account the number of times Olga had visited India since 1997, this roughly adds up to Rs 5 crore in bribes to ensure duty evasion of Rs 50 crore. Considering the fact that she was one among several Uzbek women making similar trips, the racket has meant Customs losses of hundreds of crore in a period when the rupee was worth much more.

The racket began on a modest scale in 1997 when some Indian Group B officers of the rank of superintendent and inspector were first approached. As Olga and her accomplices grew confident of getting material past Customs, the scale of their operation increased to the point that by 2000, Olga herself was walking in through immigration and Customs at IGI airport once every two or three days. The frequency of her visits alone should have triggered an alarm among security officials at immigration, but their failure to act has never been examined.

According to Olga, the man behind the scandal was an Afghan named Mamoor Khan who had left India shortly before her arrest. The arrangement with the officers was simple: even before the consignment was loaded—in Pakistan, Uzbekistan or Kyrgyzstan—the staff on duty at IGI were contacted, and they in turn would indicate which shift would be appropriate for getting the contraband through.

The network was vast and included staff at some airports where the material was loaded. The investigation found that ‘the staff of [Kyrgyzstan Airlines] at Bishkek and other places were hand in glove with offender passengers to suppress weight of excess baggage carried by them without recording the actual weight of the goods [in lieu] of illegal gratification from the offending passengers.'The airline, which was later fined, informed DRI officials that, ‘this matter has been investigated and [the] services of staff responsible including that of Mr Dusheev, Head of Manas Airport, [have] been suspended.’

In Delhi, as the flight would be about to arrive, traders from Chandni Chowk—a locality in old Delhi—would already have turned up at the airport with delivery trucks to pick up the consignment. They would pay the officials the pre-arranged bribe, and wait for the flight to land. The payment ranged from $400 to $700 a bag, depending on its size. One of the officials later admitted having received sexual favours, too, from Uzbek women.

| M K Zutshi |

The contraband, usually transported in large sacks, would then be taken out and loaded on the waiting vehicles. None of this could have been possible without the involvement of the senior staff at Customs clearance. The material was not hidden from anyone’s view, nor could it be hauled off surreptitiously. Moreover, in several cases, a nominal weight had been recorded for a much larger consignment, an assessment that could only have been made by the shift in-charge, usually a Group A official of the rank of deputy commissioner or above.

Olga’s arrest had thus exposed an airport smuggling racket unprecedented in its scope and gumption. The financial losses, while large, were not as significant as the possible threat to national security.It was to be expected that investigations would commence speedily, and end in action against the officials involved. But what has followed since is even more incredible.

The passengers - usually women - would alight with loads of baggage, sail through customs and disappear into the bylanes of Paharganj, a congested but flourishing locality adjoining the New Delhi railway station.

It worked smoothly even after the arrest on 28 August, 2000, of Olga Kozireva, the 27-year-old Uzbek who seemed to spend more time in India than in Uzbekistan. The raids on the residences of 48 officials posted at the Indira Gandhi International Airport on March 31, 2001, coincided with the raid on the house of their chief, B.P. Verma. But this exercise should have taken place at least seven months earlier, soon after Olga's arrest.

Olga’s arrest had thus exposed an airport smuggling racket unprecedented in its scope and gumption. The financial losses, while large, were not as significant as the possible threat to national security.It was to be expected that investigations would commence speedily, and end in action against the officials involved. But what has followed since is even more incredible.

The passengers - usually women - would alight with loads of baggage, sail through customs and disappear into the bylanes of Paharganj, a congested but flourishing locality adjoining the New Delhi railway station.

It worked smoothly even after the arrest on 28 August, 2000, of Olga Kozireva, the 27-year-old Uzbek who seemed to spend more time in India than in Uzbekistan. The raids on the residences of 48 officials posted at the Indira Gandhi International Airport on March 31, 2001, coincided with the raid on the house of their chief, B.P. Verma. But this exercise should have taken place at least seven months earlier, soon after Olga's arrest.

Apartments in Delhi, Noida and Kolkata. Stray investments worth Rs 40 lakh. Jewellery worth Rs 24 lakh. Loose change of about Rs 3.5 lakh; in many currencies. Few had heard of him before his arrest on 2cApril 2012.

Yet when B.P. Verma, chairman of the Central Board of Excise and Customs and the country's top revenue officer, was taken into custody for graft, criminal conspiracy and possession of assets far in excess of known sources of income, he evoked the voyeur in every Indian who had ever suffered the tyranny of the minor babu.

Verma ran a government agency 80,000-strong. He made a career of transferring people and exploiting discretionary powers.

He also lost his job, and India the taste in its mouth.

Olga, by her own admission, was a frequent visitor since 1997. Often, she would board the flight to Karachi or Lahore in Pakistan on the same day that she arrived in Delhi, and the CBI - the agency investigating the case now - is wondering whether she carried more than just textiles. Says a CBI official: "We cannot rule out the possibility of her carrying drugs or even weapons."

Two different kinds of offences were involved: one related to the criminal conduct of the officials , a case that was handed over to the CBI, and another related to smuggling that dealt with Customs and was investigated by the Department of Revenue Intelligence (DRI).

The problem became clear at the very beginning. The DRI at the time was headed by MK Zutshi, whose wife Vijaya Zutshi was commissioner at the airport till mid-2000. Moreover, DD Ingty, then additional director of the DRI, had been additional commissioner at the airport from 1997 to 1999. This may in some measure explain why the DRI took the otherwise inexplicable decision to restrict its investigation only to the year 2000.

When the case finally did come up before the Customs, Excise and Service Tax Appellate Tribunal (CESTAT), this tribunal began its conclusions and findings by stating, ‘It is shocking to read para 557 of impugned order. Learned Adjudicating Authority noticed that Ms Olga K admitted in her statement that she along with her associates was coming to India right from the year 1997. But show cause notice was issued to different persons to deal with the illegal clearances made mainly [during] the year 2000, even though extended portion was invokable (sic) for a period of 5 years…’

Uzbeks arrested on charges of smuggling fake drugs operated from hotels like Yes Please in Delhi.

|

| B P Verma |

Her links in Delhi are also suspect. Inquiries reveal that she was working in tandem with two Afghan nationals who waited outside the airport in trucks to ferry the loot. The CBI now says that there was a three-way nexus between her, the Afghans and the customs officials.

All their cell phones would begin ringing incessantly the moment Olga got off the plane, and records show that they were calling each other on the given dates.

It wasn’t surprising that no Group A officers—that is, officers of the rank of deputy commissioner who supervise shifts and their seniors—serving at the airport were part of the probe.

They were not the only ones kept out; the appellate tribunal in its judgment noted that ‘RN Zutshi (an inspector not related to the then DRI chief whose confession formed the initial basis for the investigation) has deposed unequivocally that 60 per cent of the bribe money used to go to the Preventive Department of the Airport which also manned the exit gates of the Airport. Superfluous investigations were conducted and blame was put entirely on the officers involved in baggage clearance keeping the Preventive Wing completely out of the scope of investigation, making sketchy, superficial, deliberately flawed and incomplete adjudication proposals.’

The appellate tribunal judgment, pronounced in 2011, was the result of an appeal filed against the decision of the airports commissioner who had, based on these ‘sketchy’ DRI investigations, decided to fine seven Customs officials of the rank of superintendent and below. The cumulative fines ranged roughly from Rs 2 lakh to Rs 15 lakh.

The appellate tribunal imposed a fine of Rs 1 lakh each on 14 other Custom officials who had been spared by the commissioner. These officials filed an appeal to the High Court, which sent the matter back to the appellate authority because the case against each had not been dealt with individually but been clubbed together. In what seemed a controversial move, CBI in August 2014 withdrew prosecution against five senior officers of Indian Customs and Central Excise.The five senior officers wre VK Singh Kushwaha, HR Bhima Shankar, Rajiv Gupta, Virender Kumar Choudhary and Upendra Gupta who still held senior positions and have gone on to become Joint Commissioners. 27 other junior Customs officers of Group B and C level, who were also charged by the CBI, were also off the hook.Top CBI officials pointed out that former Finance Secretary RS Gujral has written to then CBI Director AP Singh on 1 March 2012 with the approval of the then Finance Minister, Pranab Mukherjee,asking the agency to apply to the trial judge for a closure of the case against the five top officers. Then AG, GE Vahanvati, gave such a legal opinion as well, CBI said.

|

The case was repeatedly listed before a bench that did not pass the original order, even though the original bench of DN Panda and Rakesh Kumar continued to sit and he

ar other matters on a regular basis. The Revenue Department, which operates under the Union Finance Ministry, has direct control over the appellate tribunal, but it failed to take any action in this case.

The case was taken over by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) in March 2001. This agency asked the Finance Ministry for its sanction to prosecute nine group A officers and 35 Group B and C officers through the Director General (Vigilance). The Ministry finally granted this sanction in March 2006, but only against 27 officers and just five of the nine Group A officers.

The five Group A officers are VK Singh Kushwaha, then additional commissioner at the airport, apart from HR Bhima Shankar, Rajiv Gupta, Virender Kumar Choudhary and Upendra Gupta, who were all deputy commissioners.

After the framing of charges, the actual trial began only in 2011, long after the case had faded from public memory.

In a startling development since, Finance Secretary RS Gujral wrote to CBI Director AP Singh asking the agency to apply to the judge for a closure of the case against the five officers.

The letter stated that the cases were referred to the attorney general, who, after examining the charges and departmental enquiries, recommended the withdrawal: ‘It has been decided by the competent authority that the case [before the special judge, Tis Hazari] is fit for withdrawal of prosecution.’

Departmental inquiries were too closed. Deepak Garg, Deputy Commissioner (Preventive), head of the same preventive wing that came in for so much flak from the appellate authority, became a member of the DRI and was among the select few to join the Tax Research Unit in the Revenue Department, the body responsible for framing the Union Budget.

The case was taken over by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) in March 2001. This agency asked the Finance Ministry for its sanction to prosecute nine group A officers and 35 Group B and C officers through the Director General (Vigilance). The Ministry finally granted this sanction in March 2006, but only against 27 officers and just five of the nine Group A officers.

The five Group A officers are VK Singh Kushwaha, then additional commissioner at the airport, apart from HR Bhima Shankar, Rajiv Gupta, Virender Kumar Choudhary and Upendra Gupta, who were all deputy commissioners.

After the framing of charges, the actual trial began only in 2011, long after the case had faded from public memory.

In a startling development since, Finance Secretary RS Gujral wrote to CBI Director AP Singh asking the agency to apply to the judge for a closure of the case against the five officers.

The letter stated that the cases were referred to the attorney general, who, after examining the charges and departmental enquiries, recommended the withdrawal: ‘It has been decided by the competent authority that the case [before the special judge, Tis Hazari] is fit for withdrawal of prosecution.’

Departmental inquiries were too closed. Deepak Garg, Deputy Commissioner (Preventive), head of the same preventive wing that came in for so much flak from the appellate authority, became a member of the DRI and was among the select few to join the Tax Research Unit in the Revenue Department, the body responsible for framing the Union Budget.

|

| Agha,Olga's help |

Olga Kozireva served a two-year sentence before she was granted bail, which she jumped and made her way back to Uzbekistan. Only one inspector of the department, the one who admitted to sleeping with Uzbek women, was dismissed from service.

The Olga case happened when B P Verma was the head of Central Board of Excise and Customs, now known as Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs – a top policy-making body of the customs department, the officials said.

Verma, it seems, was presiding over a corrupt empire, for the Customs Department even moved the high court to try and scuttle the Olga investigation. Finally, N. Raja, director, vigilance, customs and central excise, had to put down the facts of the case in a letter to CBI Chief K. Raghavan.

The extent to which the customs officials helped Olga is quite brazen. Often, she would just walk out of the green channel, and on rare occasions, pay for part of the goods, when she should have been booked for unauthorised import of textiles. On the day of her arrest-she fell into the net because the shift had changed - the manifested cargo weight was 2,200 kg but on being weighed again it was found to be 4,375 kg.

Verma was later removed as CBEC chief for allegedly receiving illegal gratification from a Chennai-based exporter.

| A P Singh |

In a blatant attempt to hush up the case, the Customs Department approached the high court after a judge hearing her bail application in the additional sessions court observed that Olga had a dubious link with the customs officials and recommended a CBI investigation.

It sought to expunge the remarks made against them and stall the CBI inquiry. The high court granted the request.

The respite, however, was short lived. The matter came up for discussion in the Rajya Sabha towards the end of November and Finance Minister Yashwant Sinha ordered a two-pronged inquiry: from the vigilance and smuggling angles.

The probe did indeed find the officers guilty of aiding smuggling from the CIS countries and ordered the suspension of 42 of them. It didn’t happen, perhaps because of Verma’s indulgence.

The department was guilty of many more improprieties. An enterprising first secretary, Uma Suryan Arayan Mishra, posted at the Indian Embassy in Tashkent had provided detailed information on how Uzbeks and citizens of other CIS countries made frequent trips to India, carrying items like diamond powder, gold and tungsten wire.

They returned with fake medicines supplied to them at Paharganj hotels. This information was gathered from visa applicants. Records also showed that the Uzbek travellers who were being given six-month multi-entry visas were making as many as 20 trips during the period.

The Olga case was clearly only the tip of the iceberg; eight other Uzbek women were arrested on charges of smuggling and prostitution. They obviously spread their net wide, as according to the CBI, 20-40 young women were coming in on each flight from that region.

Delhi Police conducted raids on Hotel Saini International and subsequently on a banquet hall in Rajinder Nagar – a west Delhi locality-and busted a fake medicine racket. Eight quintals of medicines were recovered with wrappers printed in both Russian and Uzbek.

The medicines, Mishra pointed out, were being sold with Russian markings to pass them off as real but the authorities in Uzbekistan had woken up to the truth. Severe restrictions were imposed at Tashkent airport against import of Indian pharmaceutical products. “These activities should be monitored and controlled before they get out of hand,” the diplomat wrote in May 2000.

The government – the Home Ministry and Intelligence Bureau – too was warned about the Uzbek women, but the letters apparently remained relegated to the files. Copies of the letters from Tashkent were also forwarded to the Customs Department and, predictably, ignored.

In some cases, they were conveniently back dated. A memo sent to V.K. Singh Kushwah, additional commissioner, customs and excise, in February this year-following the internal investigation – points to this.

According to the memo, no circular or alert was issued following the Tashkent letters and worse, the alerts were “fudged” and put out only after Olga’s arrest. Kushwah was also asked to explain his decision regarding the clearing of seven bulletproof jackets brought by another CIS national, Louri Lokhov, on June 10, 2000, which the memo says “is most likely to fall in the hands of antisocial/anti – national elements”.

The scandal also highlighted another serious lapse: the Afghans- Mamoor Khan and Del Agha – are absconding. The CBI is also investigating the possibility of the customs officials having tipped them off about Olga’s arrest.

It sought to expunge the remarks made against them and stall the CBI inquiry. The high court granted the request.

The respite, however, was short lived. The matter came up for discussion in the Rajya Sabha towards the end of November and Finance Minister Yashwant Sinha ordered a two-pronged inquiry: from the vigilance and smuggling angles.

The probe did indeed find the officers guilty of aiding smuggling from the CIS countries and ordered the suspension of 42 of them. It didn’t happen, perhaps because of Verma’s indulgence.

The department was guilty of many more improprieties. An enterprising first secretary, Uma Suryan Arayan Mishra, posted at the Indian Embassy in Tashkent had provided detailed information on how Uzbeks and citizens of other CIS countries made frequent trips to India, carrying items like diamond powder, gold and tungsten wire.

They returned with fake medicines supplied to them at Paharganj hotels. This information was gathered from visa applicants. Records also showed that the Uzbek travellers who were being given six-month multi-entry visas were making as many as 20 trips during the period.

The Olga case was clearly only the tip of the iceberg; eight other Uzbek women were arrested on charges of smuggling and prostitution. They obviously spread their net wide, as according to the CBI, 20-40 young women were coming in on each flight from that region.

Delhi Police conducted raids on Hotel Saini International and subsequently on a banquet hall in Rajinder Nagar – a west Delhi locality-and busted a fake medicine racket. Eight quintals of medicines were recovered with wrappers printed in both Russian and Uzbek.

The medicines, Mishra pointed out, were being sold with Russian markings to pass them off as real but the authorities in Uzbekistan had woken up to the truth. Severe restrictions were imposed at Tashkent airport against import of Indian pharmaceutical products. “These activities should be monitored and controlled before they get out of hand,” the diplomat wrote in May 2000.

The government – the Home Ministry and Intelligence Bureau – too was warned about the Uzbek women, but the letters apparently remained relegated to the files. Copies of the letters from Tashkent were also forwarded to the Customs Department and, predictably, ignored.

In some cases, they were conveniently back dated. A memo sent to V.K. Singh Kushwah, additional commissioner, customs and excise, in February this year-following the internal investigation – points to this.

According to the memo, no circular or alert was issued following the Tashkent letters and worse, the alerts were “fudged” and put out only after Olga’s arrest. Kushwah was also asked to explain his decision regarding the clearing of seven bulletproof jackets brought by another CIS national, Louri Lokhov, on June 10, 2000, which the memo says “is most likely to fall in the hands of antisocial/anti – national elements”.

The scandal also highlighted another serious lapse: the Afghans- Mamoor Khan and Del Agha – are absconding. The CBI is also investigating the possibility of the customs officials having tipped them off about Olga’s arrest.

|

| Afghas Khan |

Says a CBI official: “She operated under the belief that she wouldn’t be touched.” Some CIS nationals even stayed for as long as a month at a stretch. Says Vinod Kumar, owner of Hotel Yes Please, a favourite with Olga: “Till her arrest, CIS nationals accounted for 60 per cent of my hotel’s occupancy.”

Hotel rooms in Paharganj come cheap, costing between Rs 150 and Rs 450 a night and are patronised by visiting Uzbeks and other CIS nationals. This corroborates reports from Tashkent that young girls, especially from the fields of entertainment and fashion designing, made as many as 30 trips in six months. This alludes to a well-organised prostitution racket in and around Delhi.

Visa applicants also revealed that they picked up jobs as agents for Herbalife, a brand name that markets food supplements. One of them, claiming to be a Herbalife consultant, had an identity card issued by the company. Photographs of Uzbek women partying and drinking have been recovered during the raids, pointing to the “hospitality” showered by the Uzbeks on the right people.

Questions are being asked about why the Government took eight months to wake up to a scandal that involved national security. Also, why was Raja chosen to head the investigation when he had himself been a commissioner, customs, in 1997 – about the time the CIS operations began?

Similarly, doubts were also raised about the competence of Revenue Intelligence chief M.K. Zutshi participated in the investigations since his wife had been the commissioner at the airport till June 2000.

Hotel rooms in Paharganj come cheap, costing between Rs 150 and Rs 450 a night and are patronised by visiting Uzbeks and other CIS nationals. This corroborates reports from Tashkent that young girls, especially from the fields of entertainment and fashion designing, made as many as 30 trips in six months. This alludes to a well-organised prostitution racket in and around Delhi.

Visa applicants also revealed that they picked up jobs as agents for Herbalife, a brand name that markets food supplements. One of them, claiming to be a Herbalife consultant, had an identity card issued by the company. Photographs of Uzbek women partying and drinking have been recovered during the raids, pointing to the “hospitality” showered by the Uzbeks on the right people.

Questions are being asked about why the Government took eight months to wake up to a scandal that involved national security. Also, why was Raja chosen to head the investigation when he had himself been a commissioner, customs, in 1997 – about the time the CIS operations began?

Similarly, doubts were also raised about the competence of Revenue Intelligence chief M.K. Zutshi participated in the investigations since his wife had been the commissioner at the airport till June 2000.

A P Singh,the CBI Director,who closed the case was arrested by CBI,on 20 February 2017,after he retired,in a graft case along with controversial meat exporter Moin Akhtar Qureshi.Qureshi,according to IT and ED,was operating as middle man for several public servants,including A P Singh.He headed the CBI in 2010-2012,during the UPA government.He was instrumental in the arrest of A Raja of 2G,Suresh Kalmadi of CWG scam.He finalized the Arushi -Hemraj double murder case. Upon his retirement,it was revealed in an IT evasion probe against Qureshi that the two regularly inter acted on daily basis,on Blackberry Messenger platform.Transcripts of conversations from Qureshi's BlackBerry Messenger revealed that not only Singh,former Directors Ranjit Sinha,Alok Verma and and Joint Director Rakesh Asthana had a had a meaty Qureshi angle to their bumpy careers.

The letter annexed full transcripts of messages Qureshi and several other individuals had allegedly exchanged on their BlackBerry Messenger during the UPA era.

|

| Moin Qureshi |

"I am also preponing my trip. Just to the homework now. And wait then we will see how to tackle it in the meantime just see who all he listens to," read a message from Qureshi to AP Singh, a former CBI director, on September 24, 2013. "May be AP or K. Nath, or someone else, also any of your friends who know him well," he added.The messages were purportedly intercepted by the Income Tax department and shared by the ED with the CBI.The Enforcement Directorate's warning, however, nowhere established the identity of individuals Qureshi wrote about. But the initials and surnames -- such as "K. Nath" and "AP" -- had a striking resemblance to some of the key figures in the then ruling United Progressive Alliance.

At the same time, the transcripts do indicate the meat trader remained in touch with AP Singh of the CBI for suspect deals in 2013.

In his response, Singh advised Quershi to get in touch with one Shinde. It's not proven whether the former CBI chief was recommending the name of then home minister, Sushil Kumar Shinde, in his reply.

"Ok let me know when you are coming back, you may need to go through Shinde," the ex-CBI director wrote.

© Ramachandran