Three Generations of Anthropologists in a Family

Dr L K Ananthakrishna Iyer was a great pioneer in the younger branches of biological sciences, namely, Anthropology and Ethnology, and his indefatigable industry and remarkable activity in fieldwork and his study have been the admiration of all who knew him intimately. The results of his labours, besides diffusing general knowledge of the customs and manners of the different groups and communities of South Indian people have created a general interest in the science itself, which has made rapid progress under his inspiring example and guidance. His life comprehended well-nigh forty years of ethnographical research.

We stand too near the period during which Dr Iyer laboured to be able to assess the real value of his accomplished work. But there is no doubt that as Anthropological studies progress in India, his contributions will be regarded as the great foundation on which the superstructure has to be built.

Ananthakrishna Iyer is best known for his books Castes and Tribes of Mysore, and Castes and Tribes of Cochin. Both are pioneering works on the tribes inhabiting India's west coast.

Dr Iyer was born in Lakshminarayanapuram, one of the Brahmin villages in Palakkad, in the Malabar district of British India, in 1861. His father L N Krishna Iyer was a Vedic scholar. Ananthan was the eldest son of Krishna Iyer's family of four sons and two daughters.

Dr Iyer's official career ranged over a very wide field and although he shifted from one appointment to another he had the power and capacity to enrich his experience. I-Ie had, therefore, opportunities of coming into intimate contact with numerous people who were his colleagues or superior officers and from his early days he developed habits of close and critical observation of men and manners. This experience formed the foundation of his later interest in anthropological research. Dr Iyer was a man slow in forming his opinions and had a very large measure of scientific scepticism which accounts for the great rigour with which he applied the scientific methods to his studies and for the great precision and clearness of his descriptions.

Dr L K Ananthakrishna Iyer was a great pioneer in the younger branches of biological sciences, namely, Anthropology and Ethnology, and his indefatigable industry and remarkable activity in fieldwork and his study have been the admiration of all who knew him intimately. The results of his labours, besides diffusing general knowledge of the customs and manners of the different groups and communities of South Indian people have created a general interest in the science itself, which has made rapid progress under his inspiring example and guidance. His life comprehended well-nigh forty years of ethnographical research.

We stand too near the period during which Dr Iyer laboured to be able to assess the real value of his accomplished work. But there is no doubt that as Anthropological studies progress in India, his contributions will be regarded as the great foundation on which the superstructure has to be built.

Ananthakrishna Iyer is best known for his books Castes and Tribes of Mysore, and Castes and Tribes of Cochin. Both are pioneering works on the tribes inhabiting India's west coast.

Dr Iyer was born in Lakshminarayanapuram, one of the Brahmin villages in Palakkad, in the Malabar district of British India, in 1861. His father L N Krishna Iyer was a Vedic scholar. Ananthan was the eldest son of Krishna Iyer's family of four sons and two daughters.

| Ananthakrishna Iyer |

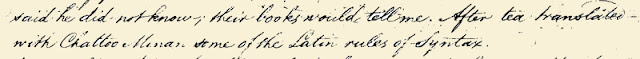

Iyer's educational career was synonymous with the development of English education in Palakkad. He completed Matriculation from the High school, which was the forerunner of Victoria CollegeHe went to Kerala Vidyasala in Kozhikode for higher studies-now Zamorin's College. At Kerala Vidyasala, he came under the notice of Barrow, the Principal of the College, with whom he was later destined to work as a colleague in the Palghat College. After FA here, he studied at Madras Christian College. He came under the influence of its Principal, Dr William Miller. He took Natural Science, but under the curriculum then in force, he had also a grounding in Psychology, Philosophy and History. Due to adverse family circumstances, he could not complete his degree then. He joined the Revenue Settlement office in Ooty as a clerk in 1888 but left in 1890 to become a teacher at Victoria College School. He worked there doing 1890-97, took his degree and also the diploma of licentiate in teaching.

Dr Iyer's official career ranged over a very wide field and although he shifted from one appointment to another he had the power and capacity to enrich his experience. I-Ie had, therefore, opportunities of coming into intimate contact with numerous people who were his colleagues or superior officers and from his early days he developed habits of close and critical observation of men and manners. This experience formed the foundation of his later interest in anthropological research. Dr Iyer was a man slow in forming his opinions and had a very large measure of scientific scepticism which accounts for the great rigour with which he applied the scientific methods to his studies and for the great precision and clearness of his descriptions.

|

| John Beddoe |

In 1897 he was headmaster of the S B High School, Changanassery for a brief period. The logbook kept at St Berchmans H S Changanacherry states, "He took charge of the school as Headmaster on 22 February 1897 He was there till May that year. Then the Cochin state offered the job of an assistant master of Science at Ernakulam Maharajas College and he settled there. For the next 23 years, he was in the Cochin service.

The turning point came in 1902 when he was appointed Superintendent of Ethnography in addition to his job at the college. His educational service ended in 1914 when his organizing capacity and scientific training were sought to create the State Museum, the Zoological Gardens in Thrissur and the Industrial Bureau. When he retired in 1920, the state issued an extraordinary gazette, which said:

"The Government desire to please on record their high appreciation of the valuable services rendered by Mr Ananthakrishna Iyer during his twenty-three years of service. His work in the field of Indian ethnology is known throughout India and Europe and has brought honour not only to himself but also to the State under which he has been employed."

The Government of India soon conferred on him the Rao Bahadur title ( 1921).

His activities after retirement, as Senior Lecturer in the Department of Anthropology, Calcutta University and officer in charge of Ethnography, Mysore for 17 years were tremendous. They form a logical continuation of the work in Anthropology he started at Cochin.

Soon after the Census of 1901, Sir Herbert H Risley inaugurated a comprehensive ethnographic survey of India. It embraced British India and the States. It was in response to this, the Cochin state agreed to take a survey of its people and appointed Iyer as the Superintendent of Ethnography. He held during 1902-1924 and carried out his work even after his retirement from the state. The results of this investigation were published from time to time in brief monographs n each caste or tribe which were later incorporated in his work, Cochin Tribes and Castes, published in two volumes (1908-1912.)

The turning point came in 1902 when he was appointed Superintendent of Ethnography in addition to his job at the college. His educational service ended in 1914 when his organizing capacity and scientific training were sought to create the State Museum, the Zoological Gardens in Thrissur and the Industrial Bureau. When he retired in 1920, the state issued an extraordinary gazette, which said:

"The Government desire to please on record their high appreciation of the valuable services rendered by Mr Ananthakrishna Iyer during his twenty-three years of service. His work in the field of Indian ethnology is known throughout India and Europe and has brought honour not only to himself but also to the State under which he has been employed."

The Government of India soon conferred on him the Rao Bahadur title ( 1921).

His activities after retirement, as Senior Lecturer in the Department of Anthropology, Calcutta University and officer in charge of Ethnography, Mysore for 17 years were tremendous. They form a logical continuation of the work in Anthropology he started at Cochin.

Soon after the Census of 1901, Sir Herbert H Risley inaugurated a comprehensive ethnographic survey of India. It embraced British India and the States. It was in response to this, the Cochin state agreed to take a survey of its people and appointed Iyer as the Superintendent of Ethnography. He held during 1902-1924 and carried out his work even after his retirement from the state. The results of this investigation were published from time to time in brief monographs n each caste or tribe which were later incorporated in his work, Cochin Tribes and Castes, published in two volumes (1908-1912.)

The publication of this evoked massive interest in the anthropological fraternity. Dr John Beddoe, in the preface, testified "to the importance and interest and to the great desirability of it being read and pondered by students of Ethnology and Sociology in England and the West generally."A H Keane, who had invited special attention in Man in March 1907 to the earlier monographs by 'this enthusiastic student of primitive peoples' wrote an introduction to this volume.

John Beddoe (1826 – 1911) was one of Victorian Britain's most prominent English ethnologists. Educated at University College, London (BA ) and Edinburgh University (M.D. 1853). He served in the Crimean War and was a physician at Bristol Royal Infirmary from 1862 to 1873. He and his wife were both friends with Mary Carpenter and they hosted what was said to be the first women's suffrage meeting in 1868. Invitees included a young Annie Leigh Browne. Beddoe retired from practice in Bristol in 1891.

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1873. In 1887 he was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society. He was a founder of the Ethnological Society and president of the Anthropological Institute from 1889 to 1891.

He died at Bradford-on-Avon on 19 July 1911.

Augustus Henry Keane (1833–1912) was an Irish Roman Catholic journalist and linguist, known for his ethnological writings. He was born in Cork, Ireland. He was educated in Cork, Dublin and Jersey, and graduated from the Roman Catholic College, in Dublin. Keane was editor of the Glasgow Free Press from 1862. He and his deputy Peter McCorry turned the first Scottish Catholic newspaper into a campaigning sheet, setting the Irish priests against the Scottish priests, and in particular the vicars-apostolic. He studied in Germany and taught at Hameln and became a linguist. He taught languages including Hindustani at the Hartley Institute, Southampton; a chair of Hindustani was created for him at University College, London, in 1883, but he left it in 1885. He then spent a period lecturing on ethnology at the University of Virginia in Charlotteville. His first important book was “History of the English Language” (1878).

Keane belonged to the "philological" group of British linguists, with Richard Garnett, Thomas Hewitt Key, Isaac Taylor, John Horne Tooke and Hensleigh Wedgwood. He began attending meetings of the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1879, read papers there, and became a Fellow, serving as vice president. He was granted a Civil List pension in 1897. Keane was a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. Keane's racial theories were published first in Nature in 1879–81. He affirmed the specific unity of human beings in his 1896 text Ethnology, even if his views had some other implications. He produced racial typologies, in his expository writings; they were more systematic than those of John George Wood and Robert Brown and were intended for rote learning. Keane was out of step with the anthropology of the time, preferring linguistic data to that of physical anthropology and came to occupy a marginal position in the emerging scientific discipline. On the other hand, his efforts at popularising anthropology were praised by Sir Harry Johnston.

Iyer's eminence as an anthropologist had been established by 1913. He was elected as President of Anthropology in the foundation session of the India Science Congress at Calcutta in 1914 with Asuthosh Mukherjee as General President. At the University of Madras in 1916 appointed Iyer as a Reader in Indian Ethnology to deliver 10 lectures.

During the eight years 1912-20, Iyer was engaged in further studies of the peoples of Cochin. The original plan was to complete the Cochin survey in three volumes, the last one being devoted to an Anthropamatic enquiry. This was interrupted by an independent enquiry on the Syrian Christians of Malabar, Cochin and Travancore. The same monograph was published by the Cochin Government Press in 1924.

The University of Calcutta invited him in 1920 to deliver a course of university readership lectures in Anthropology, after which he was appointed a lecturer in anthropology there. He remained Head of the Department and Chairman of the Board for Anthropology till his retirement in 1932. In 1924 he was appointed to complete the ethnographic survey of Mysore started by the late Dewan H V Nanjudaiya. Every year, after the University sessions in Calcutta, he proceeded to Mysore and toured the villages. After his retirement from Calcutta, he continued in Mysore as an Officer of ethnographic Survey. The work was completed in 1936 with the publication of four volumes and an appendix. He retired only by his death.

His work in Mysore comprehended a critical survey of 104 tribes and castes published in four superb volumes, most beautifully edited and illustrated. These four volumes to which prefaces and introductions were contributed by European savants such as Baron yon Eickstedt, Dr Marett and others, will always remain a monumental contribution to the descriptive science of South Indian Anthropology and should provide the basis for future anthropologists for further investigations. In the first volume which was curiously published last, he adopted a more extended canvas and discussed in great detail the ethnology of Mysore in the South Indian setting. It might be regarded as one of the finest and most exhaustive treatises on South Indian Ethnology.

Early in 1934, he was invited by European universities for lectures. At 72, the vegetarian began his voyage. His youngest son L A Natesan accompanied. He sailed on 23 April 1934 and spent about five months in Europe. Disembarking at Brindisi, he proceeded to Rome and Naples. He addressed the Department of Indian Culture of the Royal University of Rome, on 'Black Magic in India."In Florence on 14 May, he spoke on 'Primitive Culture in Southern India', at the Institute of Anthropology at the University of Florence. Towards the end of May, he arrived in Paris and spoke at the Anthropology Institute and the School of Indology under Dr Sylvain Levy. Early in June, he lectured on South Indian Culture at Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford. He then went to Austria and Germany. In Vienna, he addressed the Asiatic Society and Anthropological Society.

He next travelled to Breslau, Berlin, Konigsberg, Halle, Munchen, Heidelberg, Bonn and Cologne. His lectures were illustrated with lantern slides.

Sylvain Lévi (1863 – 1935) was an influential orientalist and indologist who taught Sanskrit and Indian religion at the École pratique des hautes études.

Lévi's book Théâtre Indien is an important work on the subject of Indian performance art, and Lévi also conducted some of the earliest analyses of Tokharian fragments discovered in Western China. Lévi exerted a significant influence on the life and thought of Marcel Mauss, the nephew of Émile Durkheim.

Dr Iyer attended the International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences in London on 30 July. It was the first international gathering of its kind. His contributions were recognised and he was elected unanimously to the Comite D'Honneur. He presented a paper,' The Agricultural Basis of Religion in India' and was Vice President of the sessions on General Ethnology and Sociology. He was back in India at the end of August 1934.

The Director of the Anthropological Institute and Ethnographical Museum of Breslau, Baron yon Eickstedt, in a communication dated September 23rd, 1930, expressed the general opinion of the European Anthropologists on Dr Iyer's works thus: " All are unanimous in that India possesses in you one of the most careful, active, and assiduous scholars of which Ethnology can boast of in any culture or country. Accordingly one finds your name mentioned with appreciation in English, German, Austrian and Italian works. The great textbook of Father W. Schmidt--who first started the connections between the Mundari and Monkhmer peoples--is full of the results of your research work and full of your instructive pictures from Southern India. This is the recognition of the fact that your works are considered to be a real storehouse of cultural and historical knowledge and are highly appreciated. We, therefore, not only honour you but venerate you as the father of Indian Ethnology... Should there be any scholar really interested in the civilisation, history and cultural future of his country, who should not know and respect your name, the name of the father of Indian Ethnology? Your admirable assiduity, your useful activity, your sound judgment and extensive knowledge are rendering you an ornament to every university, which may be so lucky as to have you in the ranks of her Professors."

After returning from Europe, He desired to take up the ethnographic survey of Coorg, which he felt was the only blank in the literature on South Indian Ethnography. He conducted this survey in the cold weather of 1934 and the summer of 1935 with Prof Lidio Cipriani, whom he had invited from the University of Florence. The manuscripts were ready for publication by February last, when he was cut off unexpectedly and without warning.

France honoured him in 1935 by electing him to the distinction of Officer D' Academie. The University of Braslau awarded him an honorary doctorate of Medicine and Surgery. In continental universities, the Department of Anthropology comes under the Faculties of Medicine.

He was five times President of Anthropology of the Indian Science Congress. On 13 February 1937, he breathed his last. To the last moment, he was apparently in the enjoyment of excellent health and spirit and those that met him at the Indian Science Congress Session in Hyderabad could hardly have imagined that his end was so near.

He was simple in his habits; did Pujas every morning, and was a man of genial temperament and unfailing courtesy. Dr. Iyer will always be remembered by his numerous friends for his great geniality, stern rectitude of character, simple habits of life, and unostentatious and unassuming manners. His scholarship was as wide as his powers of exposition were remarkable. He was happy in his domestic life, and his sons have already earnt a great reputation in the respective fields of their activity. Dr Iyer had the most lovable gift of making friends and retaining them. He never offended anyone nor made a single enemy in his long and honourable life.

His wife stood by him for 45 years. He had four sons and four daughters. Eldest son L A Krishna Iyer was an Anthropologist in Travancore. He was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1972. His second son Dr L A Narayanan was with the Geological Survey of India.Third Dr L A Ramdas in the Indian Meteorological Service and the youngest L A Natesan Professor of Economics at the Scottish Churches College, Calcutta.'

The son, Lakshminarayanapuram Ananthakrishna Krishna Iyer was an Indian Anthropologist and a writer of several books on the subject. He was the head of the department of Anthropology at the University of Madras and was credited with studies on the tribal and scheduled caste people of Kerala, a work initiated by his father, L. K. Ananthakrishna Iyer. Anthropology in India, Social History of Kerala, a two-volume historical study and The Travancore Tribes and Castes, a three-volume account of the tribal people of southern Kerala are some of his notable works. His son, L. K. Balaratnam, is also a known anthropologist. His daughter, L.K. Ganga Bhagirathy married K.A.Seetharaman, Chief Engineer of the Tamil Nadu Electricity Board.

_________________

The review of Iyer's book, Anthropology of Syrian Christians in, American Anthropologist,1930 by H D Griswold:

Anthropology of the Syrian Christians. RAO BAHADUR L. K. ANANTAKRISHNA

AYYAR. (Ernakulam: Cochin Government Press, 1926. Pp. XVII, 338.)

The appearance of this book from the pen of an Indian lecturer on Anthropology, Ancient History and Culture, Calcutta University, is more evidence

of the interest which Indian scholars are taking in the history and antiquities of their

own country. The author is already well known for his two volumes on the

Cochin Tribes and Castes.

The Syrian community in South India is the oldest Christian community in India, going back certainly to a date as early as A.D 547 when Cosmas Indicopleustes wrote, and probably much earlier. In fact, it is now fully known that there was a large commercial intercourse during the first and second centuries A D between the Roman Empire and India, or more exactly between Alexandria and the western coast of India next to Ceylon. The Periplus (A D 75) bears ample testimony for the first Christian century. Hence, as the Apostle, Paul journeyed westward to Rome, so it is quite possible that the Apostle Thomas, as tradition asserts, journeyed eastward to India, first to the capital of King Gondophares (at Taxila?) who reigned circa A.D., 20-48, and later to South India. This view is admitted as possible by S. M. Edwardes, editor of the 4th edition of Vincent Smith’s Early History of India (p. 249). Dr J. N. Farquhar in his exhaustive monograph on The Apostle Thomas in India (1916) has turned this possibility into a probability and (in the opinion of the reviewer) almost into a certainty.

The existence of Christians in South India, at least by A D 547, raises the interesting question of whether the Bhakti cult in Hinduism was influenced in any way by Christianity. Chronologically, such an influence was quite possible. Bhakti, “loving devotion,” however, has its roots in the ancient literature of India, the Bhagavadgita and the Varuna hymns of the Rigveda. Hence, if there was any Christian influence, it consisted probably only in strengthening a movement already underway long before the time of Ramanuja (11th century, A D). The case of the Madonna and Child in Christianity is somewhat similar. There was ample legendary material for a parallel Hindu development, without borrowing anything from Christianity. The presence, however, of the Christian cult of the infant Christ may have stimulated the development in the 6th century A D of the corresponding Hindu cult of the infant Krishna.

The Syrian Christians of South India have had a long and involved history. The immemorial connection between the coast of southwestern India and the Euphrates valley continued and Nestorian migrations to South India took place in the 9th century. The arrival of the Portuguese in the 16th century resulted in the winning over to Rome of a large number of Syrians and the annihilation of most of the old Nestorian influence. The division into Chaldean, Jacobite, Roman and Reformed Syrians has been a fruitful cause of controversy. The religious practices of each group are carefully described by the author.

We come now to the more strictly anthropological material contained in the book. William Crooke, the great authority on Indian folklore, has furnished a valuable introduction, stressing points of special anthropological interest.

The Syrian community has sprung almost entirely from converts recruited from the lower and middle classes, and according to the census of 1921 (as interpreted by the author) numbers about 2,62,000. The Hindu origin and environment of the Syrian community show itself in the existence of many Hindu customs, especially those connected with domestic rites. The tendency of most of the different sections into which the old Syrian community has been broken up has been to crystallize into what practically may be called “castes,” intermarriage being forbidden, though interdining is allowed. Caste prejudices still persist, including a strong feeling against low-caste people, even though they may be Christians. Marriage arrangements are made by parents, and child marriage in the past and to some extent in the present is not uncommon. Widow remarriage, however, is allowed among all sects of Syrian Christians. Childbirth takes place, as a rule, at the home of the wife’s parents. Children receive the names of maternal grandparents rather than those of the paternal line, possibly a survival of the matriarchal system which has long been in evidence on the Malabar coast.

In earlier days the Syrian Christians were not free from the practice of magic and witchcraft. Hindu astrologers were called in to fix auspicious times for domestic ceremonies. Magic circles were made on wedding days and books containing charms were used. Many of these practices were banned by the Synod of Diamper (A.D., 1599).

Appendix E contains a brief statement on the physical anthropology of the Syrian Christians, which will be supplemented shortly by volume 3 of the author’s Cochin Tribes and Castes.

© Ramachandran