A Bishop for Kollam in 1328

"In the thirteenth century, the first Latin missionaries, John of Monte Carvino, Friar Jordanus and John de Marignoli, arrived in Malabar and made converts, but their labours were ineffectual. Until the advent of the Portuguese in India, the Syrian Church was following without any hindrance, in its ritual, practice and communion, a creed of the Syro-Chaldean Church of the East. Conquest and conversion were as close to the heart of the Portuguese as were enterprise and commerce. At first they gladly welcomed the Syrians as their brethren Christians, and never thought of interfering with the doctrines, but they were soon seen to change their attitude towards them. The latter had their mother church at Babylon with their Patriarch at Mosul in Asia Minor, and were of Nestorian faith. This was shocking to Portuguese, who, after the conquest of territories and the establishment of their capital or headquarters at Goa, soon entered on a policy of conversion, and their first care was to intercept all correspondence with the eastern Patriarchs and to prevent communion with them."

Ayyar also states:"Further, it is pointed out that the Portuguese garrison at Cannanore read the Syrian Mass of the Bishops, and in A D 1348 the Syrian Christians at Quilon paid money to John Marignolli (1290-1360) as the Pope Clement's legate. "

Ayyar doesn't supply their other details.Who are they?

|

| Giovani Marignolli |

Giovanni was born, probably before 1290, to the noble Florentine family of the Marignolli. The family is long extinct, but the Via de' Cerretani, a street near the cathedral, formerly bore their name. Giovanni received his habit at the Franciscan basilica of Santa Croce at a young age. His work claims he later held the chair of theology at the University of Bologna.In 1338 he arrived at Avignon, where Pope Benedict XII held his court, an embassy from the great khan of Cathay (the Mongol emperor of the Chinese Yuan Dynasty), bearing letters to the pontiff from the khan himself, and from certain Christian Alan nobles in his service. These latter represented that they had been eight years (since Monte Corvino's death) without a spiritual guide, and earnestly desired one.

The pope replied to the letters and appointed four ecclesiastics as his legates to the khan's court. The name "John of Florence" appears third on the letters of commission. A large party was associated with the four chief envoys: when in Khanbaliq (within modern Beijing), the embassy still numbered thirty-two out of an original fifty. The mission left Avignon in December 1338; picked up the "Tatar" envoys at Naples on 10 February 1339;and arrived at Pera near Constantinople on May 1.While there, the Byzantine emperor Andronicus III pled in vain for reconciliation and alliance with the western church. Leaving June 24, they sailed across the Black Sea to Caffa on the Crimea, whence they travelled to the court of Özbeg, khan of the Golden Horde, at Sarai on the Volga. The khan entertained them hospitably during the winter of 1339-40 and then sent them with an escort across the steppes to Armalec, or Almaliq (within modern Huocheng County), the northern seat of the house of Chaghatai. "There," says Marignolli, "we built a church, bought a piece of ground... sung masses, and baptized several persons", notwithstanding that only the year before the bishop (referring to Bishop of Armalec) and six other minor friars had there undergone glorious martyrdom for Christ's salvation.

Quitting Almaliq in the winter of 1341, they crossed the Gobi Desert by way of Kumul (within modern Hami), reaching Khanbaliq in May or June 1342. They were well received by Toghon Temür, the last emperor of the Yuan dynasty in China. An entry in the Chinese annals fixes the year of Marignolli's presentation by its mention of the arrival of the great horses from the kingdom of the Folang (i.e., Farang or Franks), one of which was 11 feet 6 inches in length, and 6 feet 8 inches high and black all over. Marignolli stayed at Khanbaliq for three or four years, after which he travelled through southern and eastern China to Quanzhou (modern Xiamen), quitting China apparently in December 1347. He had been impressed by the Christian community in China, its imperial support, and Chinese culture.

Quitting Almaliq in the winter of 1341, they crossed the Gobi Desert by way of Kumul (within modern Hami), reaching Khanbaliq in May or June 1342. They were well received by Toghon Temür, the last emperor of the Yuan dynasty in China. An entry in the Chinese annals fixes the year of Marignolli's presentation by its mention of the arrival of the great horses from the kingdom of the Folang (i.e., Farang or Franks), one of which was 11 feet 6 inches in length, and 6 feet 8 inches high and black all over. Marignolli stayed at Khanbaliq for three or four years, after which he travelled through southern and eastern China to Quanzhou (modern Xiamen), quitting China apparently in December 1347. He had been impressed by the Christian community in China, its imperial support, and Chinese culture.

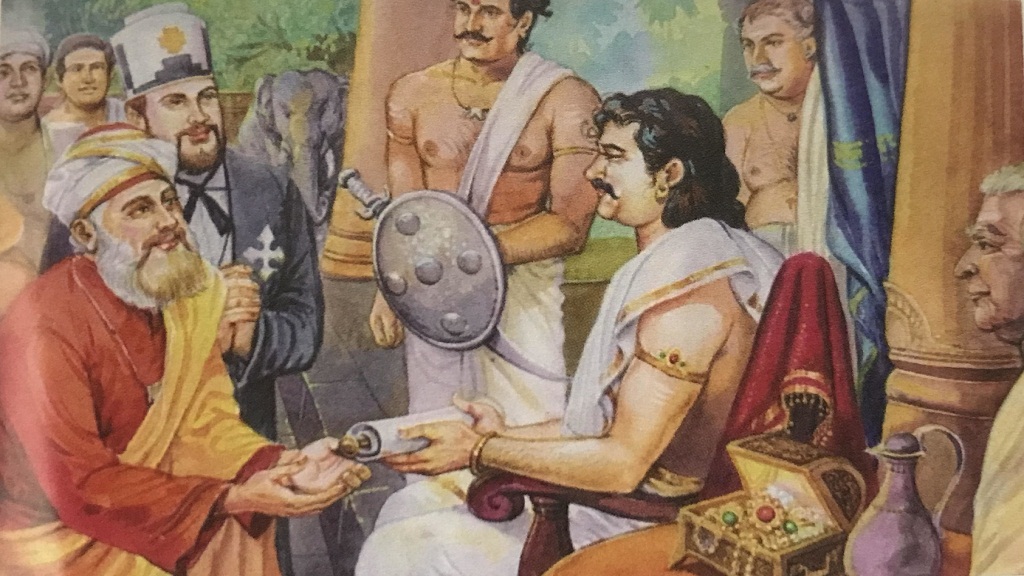

He reached Columbum (Kaulam, Kollam or Quilon in Malabar) in Easter week of 1348. He found a church of the Latin communion, probably founded by Jordanus of Severac, who had been appointed Bishop of Columbum (Diocese of Quilon) by Pope John XXII in 1330. Here Marignolli remained sixteen months, after which he proceeded on what seems very much a wandering voyage. First he visited the shrine of St Thomas near the modern Madras, and then proceeded to what he calls the kingdom of Saba, and identifies with the Sheba of Scripture, but which seems from various particulars to have been Java. Taking ship again for Malabar on his way to Europe, he encountered great storms. They found shelter in the little port of Pervily or Pervilis (Beruwala or Berberyn) in the south-west of Ceylon; but here the legate fell into the hands of "a certain tyrant Coya Jaan (Khoja Jahan), a eunuch and an accursed Saracen," who professed to treat him with all deference but detained him four months and plundered all the gifts and Eastern rarities that he was carrying home. This detention in Ceylon enabled Marignolli to give a variety of curious particulars regarding Buddhist monasticism, the aboriginal races of Ceylon, and other marvels. The locals claimed that "Seyllan" (Adam's Peak) was 40 miles from Paradise, but he was unable to explore the area.After this we have only fragmentary notices, showing that his route to Europe lay by Ormuz, the ruins of Babel, Bagdad, Mosul, Aleppo and thence to Damascus and Jerusalem.In 1353, he arrived at Naples, whence he visited Florence before returning to Avignon by the end of the year. There, he delivered a letter from the great khan to Pope Innocent VI.

In the following year the Emperor Charles IV, on a visit to Italy, made Marignolli one of his chaplains. Soon after, in March 1354, the pope made him bishop of Bisignano but he seems to have been in no hurry to reside there. He appears to have accompanied the emperor to Prague in 1354–1355; in 1356 he is found acting as envoy to the Pope from Florence; and in 1357 he is at Bologna. That year, the emperor called him to be a councillor and his court historian. At his behest, Marignolli then compiled his Annals of Bohemia.

We do not know when he died. The last trace of Marignolli is a letter addressed to him, which was found in the 18th century among the records in the chapter library at Prague.

John was born at Montecorvino Rovella, in what is now Campania, Italy.

As a member of a Roman Catholic religious order which at that time was chiefly concerned with the conversion of non-Catholics, he was commissioned in 1272 by the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos to Pope Gregory X, to negotiate for the reunion of the 'Greek' (Orthodox) and Latin churches.

|

| John of Montecorvino |

Commissioned by the Holy See to preach Christianity in the Nearer and Middle East, especially to the Asiatic hordes then threatening the West, he devoted himself incessantly from 1275 to 1286. In 1286 Arghun, the Ilkhan who ruled Persia, sent a request to the pope through the Nestorian monk, Rabban Bar Sauma, to send Catholic missionaries to the Court of the Great Khan (Mongol emperor) of China, Kúblaí Khan (1260–94), who was alleged to be well disposed toward Christianity. Pope Nicholas IV received the letter in 1287 and entrusted John with the important mission to Farther China, where about this time Venetian lay traveller Marco Polo still remained.

In 1289 John revisited the Papal Court and was sent out as papal legate to the Great Khan, the Ilkhan of Persia, and other leading personages of the Mongol Empire, as well as to the Emperor of Ethiopia. He started on his journey in 1289, provided with letters to Arghun, to the great Emperor Kúblaí Khan, to Kaidu, Prince of the Tatars, to the King of Armenia and to the Patriarch of the Jacobites. His companions were the Dominican Nicholas of Pistoia and the merchant Peter of Lucalongo. He reached Tabriz (in Iranian Azerbeijan), then the chief city of Mongol Persia, if not of all Western Asia.

From Persia they moved down by sea to India, in 1291, to the Madras region or "Country of St Thomas" where he preached for thirteen months and baptized about one hundred persons; his companion Nicholas died. From there Montecorvino wrote home, in December 1291 (or 1292), the earliest noteworthy account of the Coromandel Coast furnished by any Western European. Travelling by sea from Nestorian Meliapur in Bengal, he reached China in 1294, appearing in the capital "Cambaliech" or Khanbaliq (now Beijing), only to find that Kúblaí Khan had just died, and Temür (1294–1307) had succeeded to the Mongol throne. Though the latter did apparently not embrace Christianity, he threw no obstacles in the way of the zealous missionary. Very soon, John won the confidence of the Yuan dynasty ruler in spite of the opposition of the Nestorians who had already settled there under the name of Jingjiao/Ching-chiao .

In 1299 John built a church at Khanbaliq (now Beijing) and in 1305 a second church opposite the imperial palace, together with workshops and dwellings for two hundred persons. He gradually bought from heathen parents about one hundred and fifty boys, from seven to eleven years of age, instructed them in Latin and Greek, wrote psalms and hymns for them and then trained them to serve Mass and sing in the choir. At the same time he familiarized himself with the native language, preached in it, and translated the New Testament and the Psalms into the Uyghur used commonly by the Mongol ruling class in China. Among the six thousand converts of John of Montecorvino was a Nestorian Ongut prince named George, allegedly of the race of Prester John, a vassal of the great khan, mentioned by Marco Polo.

John wrote letters of 8 January 1305 and 13 February 1306, describing the progress of the Roman mission in the Far East, in spite of Nestorian opposition; alluding to the Roman Catholic community he had founded in India, and to an appeal he had received to preach in "Ethiopia" and dealing with overland and oversea routes to "Cathay," from the Black Sea and the Persian Gulf respectively.

After he had worked alone for eleven years, the German Franciscan Arnold of Cologne was sent to him (1304 or 1303) as his first colleague. In 1307 Pope Clement V, highly pleased with the missionary's success, sent seven Franciscan bishops who were commissioned to consecrate John of Montecorvino archbishop of Peking and summus archiepiscopus 'chief archbishop' of all those countries; they were themselves to be his suffragan bishops. Only three of these envoys arrived safely: Gerardus, Peregrinus and Andrew of Perugia (1308). They consecrated John in 1308 and succeeded each other in the episcopal see of Zaiton (Quanzhou), which John had established. In 1312 three more Franciscans were sent out from Rome to act as suffragans, of whom one at least reached East Asia.

For the next 20 years the Chinese-Mongol mission continued to flourish under his leadership. A Franciscan tradition that about 1310 John of Montecorvino converted the new Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, also called Khaishan Kuluk (he was also the third Emperor of the Yuan dynasty; 1307–1311) is disputed. His mission unquestionably won remarkable successes in North and East China. Besides three mission stations in Peking, he established one near Amoy harbour, opposite Formosa island (Taiwan).

John of Montecorvino translated the New Testament into Uyghur and provided copies of the Psalms, the Breviary and liturgical hymns for the Öngüt. He was instrumental in teaching boys the Latin chant, probably for a choir in the liturgy and with the hope that some of them might become priests.

He converted Armenians in China and Alans to Roman Catholicism in China.

John of Montecorvino died about 1328 in Peking. He was apparently the only effective European bishop in medieval Peking. Even after his death, the mission in China endured for the next forty years.

Togun Themur,the last Mongol (Yuan dynasty) emperor of China, sent an embassy to the French Pope Benedict XII in Avignon, in 1336. The embassy was led by a Genoese in the service of the Mongol emperor, Andrea di Nascio, and accompanied by another Genoese, Andalò di Savignone.These letters from the Mongol ruler represented that they had been eight years (since Montecorvino's death) without a spiritual guide, and earnestly desired one. The pope replied to the letters, and appointed four ecclesiastics as his legates to the khan's court. In 1338, a total of 50 ecclesiastics were sent by the Pope to Peking, among them John of Marignolli. In 1353 John returned to Avignon, and delivered a letter from the great khan to Pope Innocent VI. Soon, the Chinese rose up and drove the Mongols from China, thereby establishing the Ming Dynasty (1368). By 1369, all Christians, whether Roman Catholic or Syro-Oriental, were expelled by the Ming rulers.

Six centuries later, Montecorvino acted as the inspiration for another Franciscan, the Blessed Gabriele Allegra to go to China and complete the first translation of the Catholic Bible into Chinese in 1968.

Jordanus (fl. 1280-c. 1330), distinguished as Jordan of Severac (Latin: Jordanus de Severac; Occitan: Jordan de Séverac; French: Jourdain de Séverac; Italian: Giordano di Séverac) or Jordan of Catalonia (Latin: Jordanus Catalanus; Catalan: Jordà de Catalunya), was a Catalan Dominican missionary and explorer in Asia known for his Mirabilia Descripta describing the marvels of the East. He was the first bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Quilon, the first Catholic diocese in India.

Jordanus was perhaps born at Sévérac-le-Château, north-east of Toulouse. Possibly a disciple of Jerome de Catalonia, also known as Hieronymus Catalani,in 1302 Jordanus may have accompanied St Thomas of Tolentino, via Negropont, to the East; but it is only in 1321 that we definitely discover him in western India, in the company of Thomas and his companions. Ill-luck detained them at Thane in Salsette Island, near Bombay; and here Jordanus's companions were killed on 8 and 11 April 1321.

Jordanus, escaping, worked some time at Bharuch, in Gujarat, near the Nerbudda estuary, and at Suali (?) near Surat; to his fellow-Dominicans in north Persia he wrote two letters — the first from Gogo in Gujarat (12 October 1321), the second from Thane (24 January 1323/4) describing the progress of this new mission. From these letters we learn that Roman attention had already been directed, not only to the Bombay region, but also to the extreme south of the Indian peninsula, especially to Columbum, Quilon or Kollam in later Travancore; Jordanus' words may imply that he had already started a mission there before October 1321.

From Catholic traders Jordanus had learnt that Ethiopia (i.e. Abyssinia and Nubia) was accessible to Western Europeans; at this very time, as we know from other sources, the earliest Latin missionaries penetrated thither. Finally, the Epistles of Jordanus, like the contemporary Secreta of Marino Sanuto (1306–1321), urge the Pope to establish a Christian fleet upon the Indian seas.

|

Jordanus, between 1324 and 1328 (if not earlier), probably visited Kollam and selected it as the best centre for his future work; it would also appear that he revisited Europe about 1328, passing through Persia, and perhaps touching at the great Crimean port of Soidaia or Sudak. He was appointed a bishop in 1328 and nominated by Pope John XXII in his bull Venerabili Fratri Jordano to the see of Columbum or Kollam (Quilon) on 21 August 1329. This diocese was the first Roman Catholic one in the whole of the Indies, with jurisdiction over modern India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Burma, and Sri Lanka. It was created on 9 August by the decree Romanus Pontifix. Together with the new bishop of Samarkand, Thomas of Mancasola, Jordanus was commissioned to take the pallium to John de Cora, archbishop of Sultaniyah in Persia, within whose province Kollam was reckoned; he was also commended to the Christians of south India, both east and west of Cape Comorin, by Pope John.

Either before going out to Malabar as bishop, or during a later visit to the west, Jordanus probably wrote his Mirabilia, which from internal evidence can only be fixed within the period 1329–1338; in this work he furnished the best account of Indian regions, products, climate, manners, customs, fauna and flori given by any European in the Middle Ages — superior even to Marco Polo's. In his triple division of the Indies, India Major comprises the shorelands from Malabar to Cochin China; while India Minor stretches from Sind (or perhaps from Baluchistan) to Malabar; and India Tertia (evidently dominated by African conceptions in his mind) includes a vast undefined coast-region west of Baluchistan, reaching into the neighborhood of, but not including, Ethiopia and fictitious Prester John's domain. Jordanus' Mirabilia contains the earliest clear African identification of Prester John, and what is perhaps the first notice of the Black Sea under that name; it refers to the author's residence in India Major and especially at Kollam, as well as to his travels in Armenia, north-west Persia, the Lake Van region, and Chaldaea; and it supplies excellent descriptions of Parsee doctrines and burial customs, of Hindu ox-worship, idol-ritual, and suttee, and of Indian fruits, birds, animals and insects. After 8 April 1330 we have no more knowledge of Bishop Jordanus I.

Either before going out to Malabar as bishop, or during a later visit to the west, Jordanus probably wrote his Mirabilia, which from internal evidence can only be fixed within the period 1329–1338; in this work he furnished the best account of Indian regions, products, climate, manners, customs, fauna and flori given by any European in the Middle Ages — superior even to Marco Polo's. In his triple division of the Indies, India Major comprises the shorelands from Malabar to Cochin China; while India Minor stretches from Sind (or perhaps from Baluchistan) to Malabar; and India Tertia (evidently dominated by African conceptions in his mind) includes a vast undefined coast-region west of Baluchistan, reaching into the neighborhood of, but not including, Ethiopia and fictitious Prester John's domain. Jordanus' Mirabilia contains the earliest clear African identification of Prester John, and what is perhaps the first notice of the Black Sea under that name; it refers to the author's residence in India Major and especially at Kollam, as well as to his travels in Armenia, north-west Persia, the Lake Van region, and Chaldaea; and it supplies excellent descriptions of Parsee doctrines and burial customs, of Hindu ox-worship, idol-ritual, and suttee, and of Indian fruits, birds, animals and insects. After 8 April 1330 we have no more knowledge of Bishop Jordanus I.

Siddhartha Sharma,in Carpenters and Kings:Western Christianity and the Idea of India has discussed,the travelogue,Mirabilia Descripta, of Jordanus.lacks the real picture of the India;Jordanus found that the men of India went to war in their loincloths, with a small shield and a spear, an observation made by Giovanni before him. He appears to not have met or studied the great armies in the interior, nor does he seem to have been interested in the formidable arms and armour of indigenous soldiers or Turkish cavalrymen, or the flourishing export trade of Indian steel for swords and other weapons to the Middle East.Jordanus did not describe the funerals of the poor, but he did witness the custom of sati, which was also noted in some detail by Ibn Battuta.Jordanus was also the first European to meet and observe the Parsi community of India along the coast of Gujarat and the northern Konkan region. Speaking of the different kinds of funerals in the subcontinent, he talked of these people who neither burnt nor buried their dead but cast them into massive towers without roofs, where carrion birds would eat the bodies.

Most Indians were idol worshippers, although Jordanus found that Muslims had made considerable inroads from Sindh just prior to his arrival. He wrote of numerous Hindu temples and Syrian Christian churches which had been destroyed or converted into mosques.Jordanus seems to have visited many Hindus temples and held discussions with the priests about their beliefs. The discussions were amicable and instructive enough for him.Jordanus was fascinated by the multitude of Hindu gods and their forms, and the kinds of idols worshipped in the land. But above all these gods, there was supposed to be a single, all-powerful deity, according to what he was told by his sources. Jordanus was also told by Hindu scholars that the age of the world, by their reckoning, was 28,000 years, which was considerably lower than what the Puranas composed in the Middle Ages hold, but was still longer than the same according to biblical reckoning.Missionaries would be treated with warmth and respect by Hindus across the land, and their safety would be ensured. Whenever a Hindu chose to be baptised, the people or the authorities would not create any hindrance or persecute either the convert or the missionary. This freedom, said the Dominican, was common to Hindu and Mongol societies and among other people east of Persia in his time. While all Hindus honoured cattle like their own parents, most also worshipped them with the reverence seen for their gods. In most regions, the act of slaughtering cattle was considered as terrible a crime as parricide. A person who had murdered five men was more likely to receive a mitigated sentence than someone who had killed a cow.

Somewhere along the Saurashtra coast or in northern Konkan, Jordanus was told of a prophecy the Indians had: that the Latin Christians would, one day, rule the world!

© Ramachandran

.jpg)